by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

The antithesis between abstract and realistic art, which lasted for a long time in the 1950s, was overcome during the decade which — although difficult to reduce to a common denominator — can be grouped under the definition of “informal.” This term, used for the first time in 1951 by the critic Georges Mathieu, obviously in its French sense, appears to be preferable to others — tachisme, that alludes to a painting with irregular spots (tache = spot); action painting, which refers to a sort of submission of the language to gesture, to action; lyrical abstractionism — precisely because of its generic nature, which lends itself to giving a minimum of unity to not very similar experiences.

Informal art, not only a European phenomenon, has its roots in the climate of mistrust in the cognitive abilities of reason, that arose following the Second World War. The deep devaluation of conventional means of expression — form and color — leads artists to focus their explorations on material, sign and spot. The premises of the informal are to be found in works by fairly isolated artists, active in the last years of the war in New York (Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning) and Paris (Wols, Jean Fautrier, Jean Debuffet). But mostly, it is in America where action painting arises, and indeed, Paris has lost its role as artistic capital since then.

Common elements are the detachment from history, even from the history of art, and often the refusal of political commitment: for many weighed the disappointment felt in having seen the hopes lit at the end of the conflict gradually vanished. The philosophical currents of the time (above all existentialism) accounted for the precariousness of life and paralyzing anguish, and from which there was no escape by gestures of revolt. The artist, having relations with reality become precarious, anxiously looked for an original and primitive artistic creativity.

The movement was influenced by the art of the Russian Vasilij Kandinsky, but also by surrealism, which sought to express the unconscious most directly and spontaneously. The main thrust, which gives impulse to the movement, is fueled by the artist’s need for improvisation, spontaneity and motor movement. The artist acts by giving free rein to his unconscious, and in this way he frees himself from the anguish and his restlessness with the physical movement of painting.

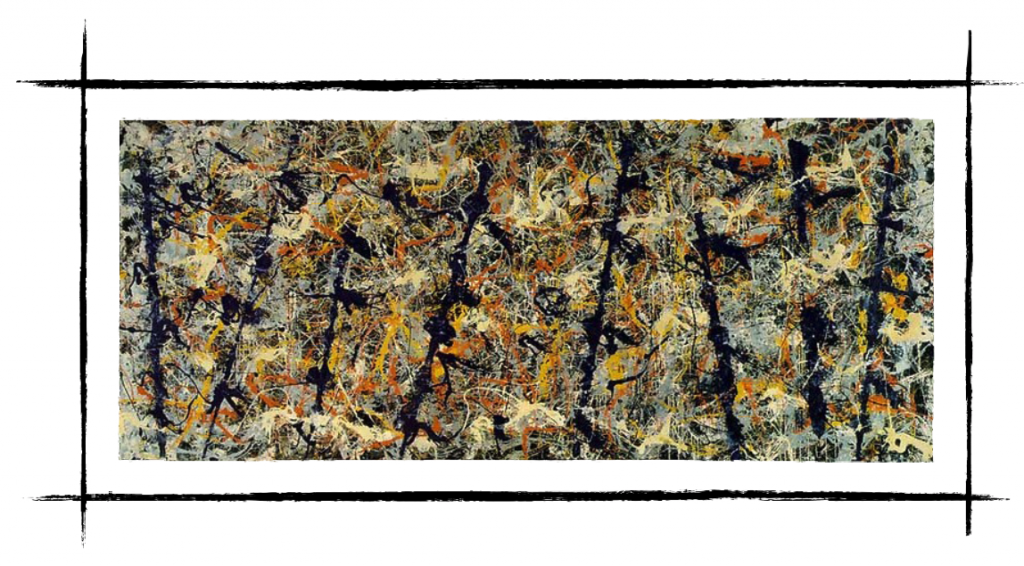

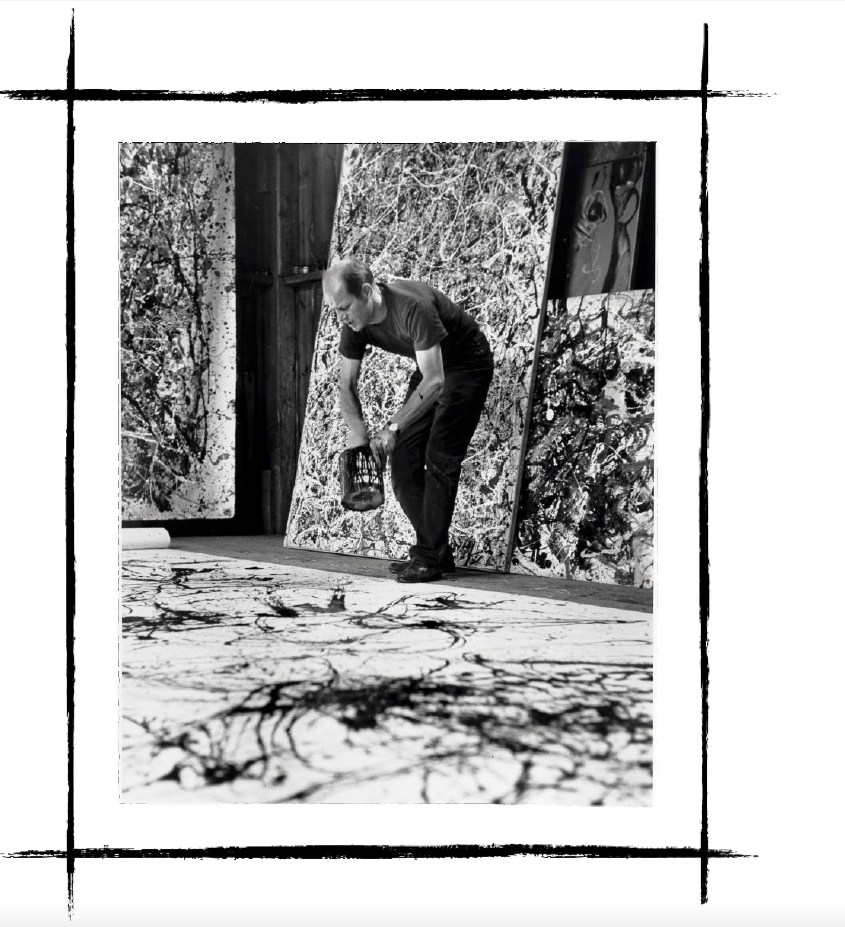

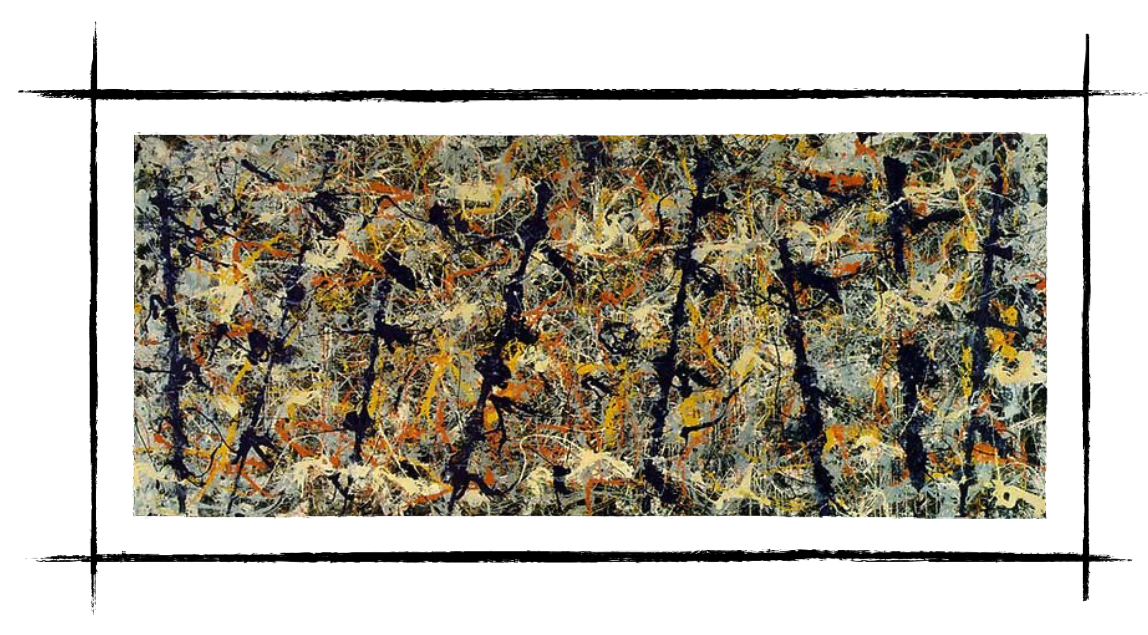

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) founder of American action painting, sought in a technique of automatism, similar to certain surrealist proposals, the way to free creativity from the unconscious. In this way he made his painting progressively more abstract until he made his first works in 1946 with the procedure called by himself, dripping, consisting in dripping, precisely, the color from a brush or a stick onto the canvas spread on the floor. The movement of the artist’s hand created an intricate set of lines on the surface, according to a more or less convulsive “rhythm” that has quite reasonably been compared to a piece of jazz music. Art, for Pollock, therefore loses its cognitive purposes, becomes an act of violent, angry participation, a testimony to the malaise in which the new generations find themselves.

Pollock also said that, spreading the canvas on the ground, it was better to walk around it and he felt an integral part of the picture. In the course of his experimentation he made some studies on the radiation of the Native American Indians and realized that the prayers addressed to the “Gods” took place through repeated turns of the Indians around the fire, during a state of trance and semi-awareness. From this experience Pollock associated the canvas to the fireplace, and the painter to the shaman. This union will transmit all of its most intimate interiority to future paintings, thanks to an accurate and spiritual escape from reality.

It is the artist’s ego that looms completely over the painting, and it is the painting itself that commands like the fire in a shamanic rite. Action painting never shows nor expresses an objective or subjective reality, but releases a tension that has accumulated in large quantities in the artist. It is an action not conceived and not planned in the ways of execution and in the final effects. It expresses the artist’s malaise in a well-structured society where everything is planned; it is a violent reaction of the artist-intellectual against the artistic-technician. “When I’m inside my paintings,” said Pollock “I’m not fully aware of what I’m doing. Only after a moment of awareness I realize what I have achieved. I am not afraid to make changes or to spoil the image, because the painting has a life of its own. I try to get it out. It is only when I happen to lose touch with the painting that the result is confusing and poor.”

Pollock’s drippings do not want to hit the viewer with colors or with a pleasant appearance, but only be the testimony of the artist’s life and presence. This is why observing the painting does not convey anything to us; because we have to think about the action that happens first, what Jackson did on the canvas. The painting is only the result, the work of art is the process of creation. To help understand the purpose of his works, in the 1950s Jackson began a collaboration with his friend and photographer Hans Namuth, creating some extraordinary photo shoots that portray the artist at work. There are more than 500 black and white shots where we see Pollock using brushes as sticks and “splashing” the paint directly on the canvas. Jackson chooses huge canvases for two specific reasons: the first is to represent the power of the United States, which after World War II will become the first world power. The second is to show the artist’s physical strength, who also sees the canvas as a sort of “gymnasium”.

The constraints of reason have little to do with art. Dripping is a true hymn to freedom, to the point that Pollock soon stopped giving a title to his works to limit himself to numbering them. If there had been a title, he argued, the observer would have been conditioned in some way. The canvases had to speak to each one only through color, leaving aside all that was rational. Words included.

=======

Homepage: https://carlkruse.net

Contact: info AT carlkruse DOT net

Also by Asia Leonardi: The Photography of Francesca Woodman

MOMA’s artist page on Jackson Pollock here.

Also find Carl Kruse and his photographs on Fstoppers.

Beauty and even a certain order amid the chaos, no?

I would say so. Pollock certainly showed us a different, way, direction, no?

Carl Kruse

For a while laughed at for being NOT art. Now at the pinnacle of artistic expression. How things can change.

Indeed.

Carl Kruse

I can’t think of another painter whose approach was so vindicated long after he was gone.

Maybe van Gogh? Mondrian? Maybe some of the Pop artists?

Carl Kruse