by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

The graphic art of Maurits Cornelis Escher is different from that of any other artist, instantly recognizable to millions of people around the world, representing an always compelling combination of art and mathematics.

Escher’s world, which explores issues of infinity and paradox, of impossible geometry and perspective distortion, is animated by a playful imagination and the unexpected, crafted with precision and an extraordinary attention to detail.

Born in Leeuwarden, the Netherlands, on June 17, 1898, Escher did not shine particularly well in the early years of school due to health problems, yet, he showed artistic talent and in 1919 he enrolled at the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts. He began studying architecture (a subject that would have fascinated him throughout his career) but after a short time, switched to the decorative arts with courses in drawing and wood engraving. Escher left school in 1922 and went on a tour of Spain and Italy that would significantly influence his later works.

During his travels, he met Jetta Umiker, whom he married in 1924, and for the following 11 years, the couple lived in Rome. Escher explored Italy far and wide, creating sketches and drawings, many of which reveal a growing interest in perspective distortion. Later, the artist would take these early elaborations to the extreme, basing his works on “impossible objects,” such as the famous and confusing Necker’s Cube and Penrose’s Triangle.

Under Mussolini’s regime, life in Italy became intolerable and in 1935 the family moved to Switzerland. 1936 was an important year for Escher and saw the transition in his works from natural landscapes to interior landscapes. He also saw the beginning of a lifelong fascination with tessellated shapes, inspired by a visit to the Alhambra. Escher called this new technical elaboration the “Regular Division of the Plane”. In 1937 the prints Still Life and Street and Metamorphosis I already testified to the essence of many of Escher’s new concepts: ambiguity, impossible reality, metamorphosis, altered perspectives, which would become dominant themes for the rest of his career.

After moving to Belgium in 1937, Escher returned to his Nazi-occupied country in 1941, where he would remain until 1970. These were years of great production and inspiration. After the war, the exhibitions earned him international fame and honors, including a knighthood. In the course of his life, Escher made 448 lithographs, woodcuts on wood or heads, and over 2000 sketches. His images bring to life the unreal, the paradox and the incomprehensible, with results that few others have equaled. In 1970 Escher moved to a retirement home for artists where he continued to have a studio. He died on March 27, 1972.

“I always move between puzzles. Some young people come to me to tell me: yours is Op Art too. I have no idea what Op Art is. I’ve been doing this job for 30 years.

Smaller and Smaller, 1956 | wood engraving and woodcut in black and red-brown printed from four blocks | 38 x 38 cm

Smaller and Smaller is an extraordinary example of Escher’s “Regular Division of the Plane” and also testifies to the artist’s interest in infinity. The lizards, arranged so that noses and tails coincide, are elegantly arranged in a vortex until they disappear into the infinitely small in the center. The work was created in 1956, the year that marks the moment when Escher began to take a research interest in expressing the infinite with tessellations. His interest was piqued by discussions with the mathematician Harold Coxeter, during which the two studied the possibility of combining the artist’s principle of “Regular Division of the Plane” with Coxeter’s geometric figures.

Escher himself often pointed out that he did not receive a formal education in mathematics, however, in works such as Smaller and Smaller and others, he achieved perfect accuracy within complex geometric theories. As Coxeter reiterated in 1995 “Escher is absolutely accurate, down to the millimeter.”

“Only those who measure themselves against the absurtd will achieve the impossible. I believe it’s in my basement..Now I go up and check.

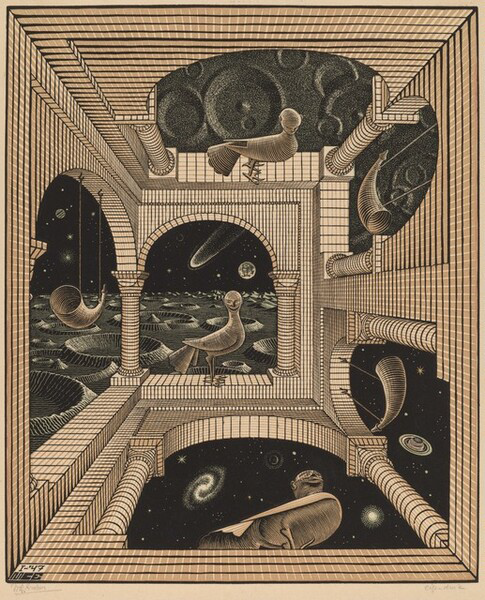

Other World (Another World), 1947 | wood engraving and woodcut in black, light browning green printed from three blocks | 31,5 x 26 cm

Other World, also known as Another World, the first of Escher’s prints to explore his idea of relativity, is a study of the relationship between objects. The artist presents to the viewer a structure with five open walls, with almost identical Romanesque arches that offer a view on a series of different panoramas. The two arches at the base present an upward perspective on space, the two upper ones look down on a lunar landscape and the two in the center on a lunar horizon. The image, therefore, creates a paradox: each floor could be both the zenith and the nadir of the structure, so everything is relative depending on where you look. The image also features a bird with a human face perched on three arches, while a horn hangs from three other arches. The bird is the representation of a small sculpture donated to Escher by his father-in-law, and is present in several works by the artist.

“Are you really sure that a floor cannot be also a ceiling?”

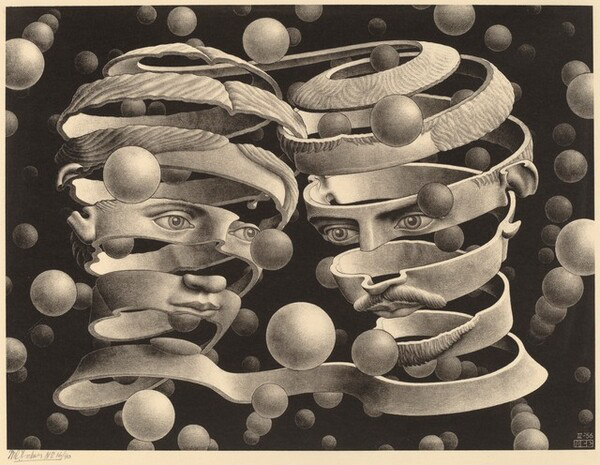

Bond of Union, 1956 | lithograph 26 x 34 cm

The heads of a man and a woman float in the darkness and are formed by a single spiral ribbon that also joins them for the forehead. Infinite space-time is suggested by the spheres, similar to small planets, suspended in front, behind and inside the heads. Bond of Union is one of Escher’s most representative works and was inspired by the reading of “The Invisible Man”, the novel by H. G. Wells in which the hero has his head wrapped in bandages.

In this work, once again, the image expresses the artist’s exploration of the infinite. Moreover — an uncommon aspect of Escher, more interested in paradox, geometry and unreality than in “human” issues — he recalls the myth of Adam and Eve, and the bonds that keep men, women, and all humanity together. In this sense it is one of Escher’s most touching and most surprising works.

“The things I want to express are so beautiful and pure.”

===========================

Carl Kruse Art Blog Homepage is here.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Also by Asia Leonardi: The Photography of Francesca Woodman, Jackson Pollock’s Hymn To Freedom.

The official Escher website: https://mcescher.com/

Find Carl Kruse on Hackernoon.

Love, love, love Escher. So ahead of his time. Well done Asia Leonardi!

Thanks for stopping by Tobias. Is there anyone not captivated by Escher? And isn’t Asia great?

Carl Kruse

Since a little girl I have been fascinated with M.C. Escher.

My guess is many of us have been fascinated with Escher’s art from the get go.

Carl Kruse