By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

In the church of Florence of San Salvatore Ognissanti, where the secular exponents of her family are exhibited, rests today the beautiful Simonetta Vespucci in her secular sleep. But there was a time when the prodigious beauty was the inspiring muse of major Renaissance artists, such as Piero Cosimo, Verrocchio, Filippo Lippi, and one of the great interpreters of the Renaissance, Sandro Filipepi, known as Botticelli. The face of the lady was the most famous of the fifteenth century, reproduced in countless prints and on postcards depicting Renaissance masterpieces. Simonetta Vespucci was defined by her contemporaries as the “Living Venus.”

Simonetta was born in Genoa (or Porto Venere) in the year 1453, from the noble family of Cattaneo, in decline after the fall of Constantinople, the city to which they had linked their trade. She was only 16 when she married Marco Vespucci, an acquaintance that came to her through her mother’s family, more precisely from the lord of Piombino, Iacopo III Altopiano. Marco Vespucci came from a

line of Florentine bankers, to which the well-known Amerigo belonged, the one who gave his name to America. It is known that at the time the marriage between the exponents of the wealthy classes did not contemplate the importance of feelings and was essentially a suitable contract for consolidating assets and alliances (remember, in this case, the sweet letters written by Eloisa

to her Abelard, three centuries earlier, which described marriage as captivity, and adultery alone as the principle of true love), the testimonies of the time attest that the groom was sincerely in love with Simonetta. The union of the two young people, due to the importance of the families involved, had a wide resonance and was celebrated in the presence of the Doge of Genoa and the

local aristocracy.

When Simonetta and Marco moved to Florence, Lorenzo the Magnificent had just come to power. Under his enlightened government, and thanks to the skillful use of patronage as an instrument of political propaganda, Florence experienced a splendid cultural flowering. Theater of amazing encounters, crossed by minds such as Marsilio Ficino, Pico Della Mirandola, great painters such as Sandro Botticelli, Michelangelo, souls all close to the Medici, who became the protagonists of an unrepeatable artistic season that remains, in many respects, unmatched throughout history.

In this scenario, Simonetta made her first entry into the city of Florence. Under the excellent relations between their families, Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano welcomed the couple in the Palazzo Medici in Via Larga (which currently bears the name of via Cavour, in Florence) and organized a sumptuous feast in their honor in the villa of Carreggi. From that moment on, the couple continued to animate court life in a crescendo of sumptuous parties, rich banquets, and joyful pastimes.

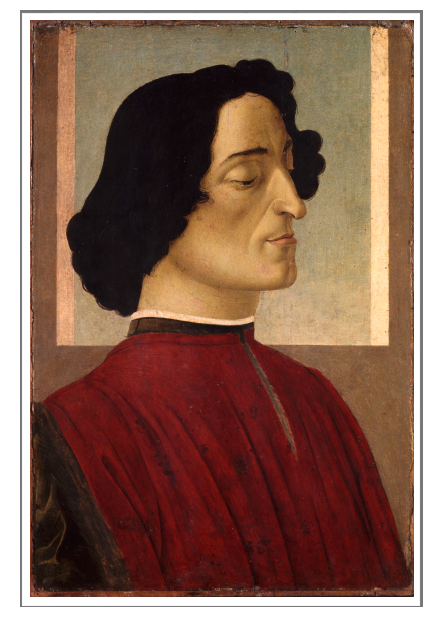

Simonetta’s adolescence, meanwhile, had turned into splendid beauty, giving her a slender body with a pale complexion, large, clear eyes that illuminated her face framed by wavy blond hair. At the time, all the most prominent young people in Florence were conquered by her grace, first of all, Lorenzo’s younger brother, Giuliano, who in the meantime, with great probability, became her lover.

In 1475, Giuliano, bedecked in dazzling silver armor studded with precious stones, and a helmet designed by Verrocchio, won, in Piazza Santa Croce, the knightly tournament that sealed the peace agreement made by Lorenzo the Magnificent with the other Italian powers. The palio for which the contenders were disputing was a flag, perhaps painted by Botticelli, in which Simonetta, crowned queen of the tournament, appears in the guise of Athena, with her feet resting on a burning olive branch, on which a scroll is placed with the French motto “La Sans Par” (“the incomparable”). The entire composition referred to the theme of courtly love, a great passion for medieval troubadours, for which

the beloved woman was considered sublime and unattainable. The event went down in history as the “Julian Tournament,” since it was a worldly event of great public visibility, celebrated with praise by many of the intellectuals of the time. In Angelo Poliziano’s “Stanze per la giostra di Giuliano de’ Medici” Simonetta appears decorated with these verses:

She is white, and her dress is white / But even

with roses and painted flowers and grass: / The

ringed crin of the golden head / Descends into

the humbly proud forehead.

In the opera, unfinished due to the death of the protagonist on the Pazzi Conspiracy of 1478, Poliziano sings of Giuliano’s love for Simonetta. The life of the young de Medici is abruptly interrupted, and the end of the beloved woman is no different, even though she seemed to wear a beauty immune from all pains and difficulties: the plague, chose to take her away on April 26, 1476, when she was still 23 years old.

Lorenzo learned about his friend’s condition while he was staying in Pisa, and asked to be constantly informed of her health through an exchange of letters with her father-in-law, Piero. He even went so far as to send his doctor to the Vespuccis for a consultation. It was his agent, Sforza Bettini, who told him the news of the young woman’s death, who inspired the four sonnets at the opening of his work, entitled “Comment on my Sonnets,” to the Magnifico.

In the notes to the sonnets, taking a cue from the description of Beatrice in Dante’s Vita Nova, Lorenzo imagined that he had received the inspiration to compose the work one night, after having observed a bright star, which could only be the soul of the young Simonetta ascendeding to heaven to enrich the firmament.

O clear star that with your rays / Remove the

light from your nearby stars, / Why do you shine

much more than your costume? / Why do you

still want to contend with Febo? / Perhaps and

beautiful eyes, which have been taken away from

us / by Cruel death, which by now assumes too

much, / You have welcomed in you: adorned

with their divinity, / his beautiful chariot you

can ask Phoebus. / Or this, new star that you

are, / That adorns the sky with new splendor, /

Called hear, god, and our vows: / Lever of your

splendor so far, / That in the eyes, they have

eternal weeping zeal, / With no offense glad you

show yourself.

No less moved was the tone in which Bernardo Pulci recalled the uncovered funeral granted to the beautiful Vespucci:

But perhaps that still alive in the world is the one

/ then that seen by us was, after the end, / in the

coffin even more beautiful.

A stunning honor for those times, reserved by law for knights only. Simonetta’s death was also wept by Girolamo Beniveni, by Naldo Naldi in two epigrams, and by Francesco Nursio Veronese in a poem. But what made the charming lady immortal was painting above all else, although, in all probability, she never posed for a painting. For a lady of her rank to pose would have been judged contrary to decency and social conventions; it was only in the sixteenth century that it became more common for high-bourgeois women to be portrayed by an artist. Vasari in the “Vite dei piú eccellenti pittori, scultori e archittettori” (“Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors, and architects”) writes of how two portraits were preserved in the wardrobe of Duke Cosimo I, one of which, he recalls, “it is said that was the one in love with Giuliano de ‘Medici” executed by Botticelli. But was the young woman in question Simonetta, or was she another woman loved by the handsome Giuliano?

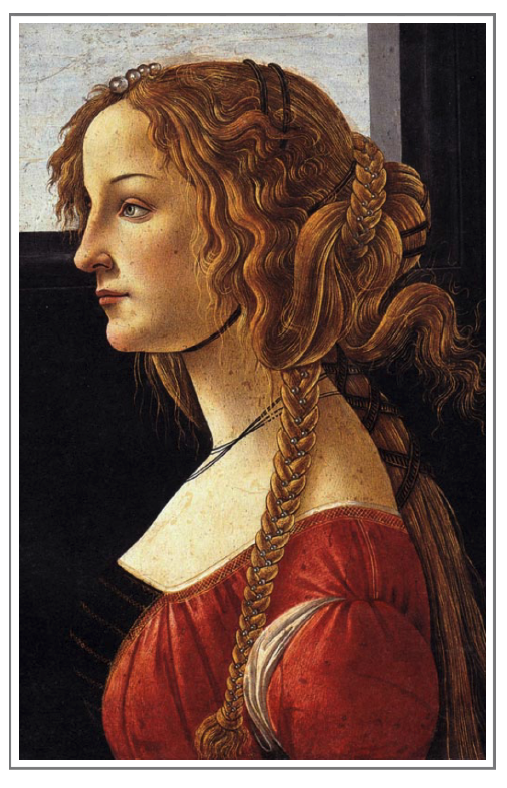

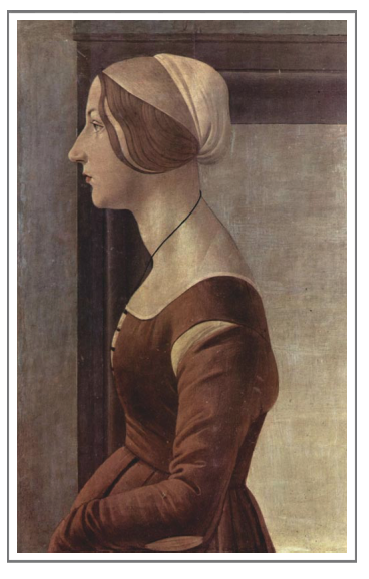

Academics still dispute today on the identification of the portrait cited by the Arezzo man: was it perhaps the “Portrait of a Lady” from the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, that of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, or the “Portrait of a Young Woman” from the Palatine Gallery in Florence?

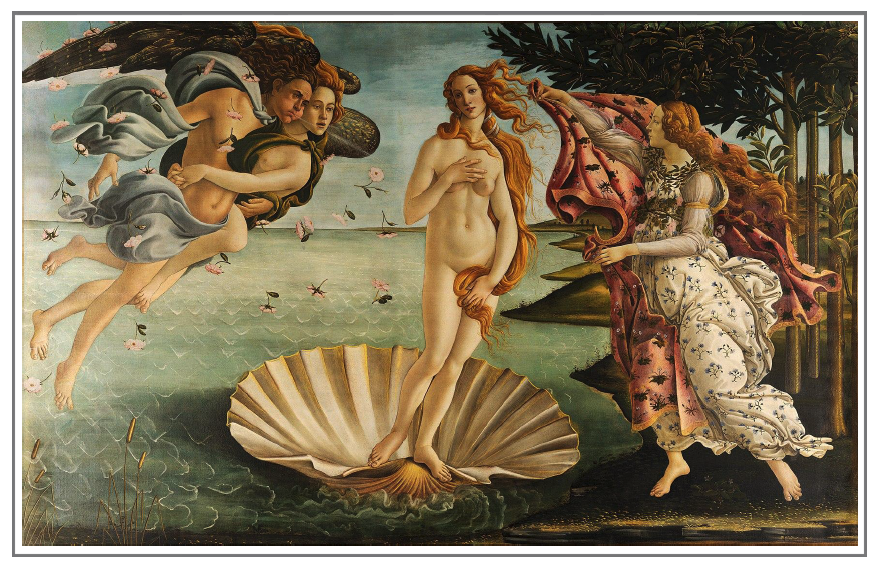

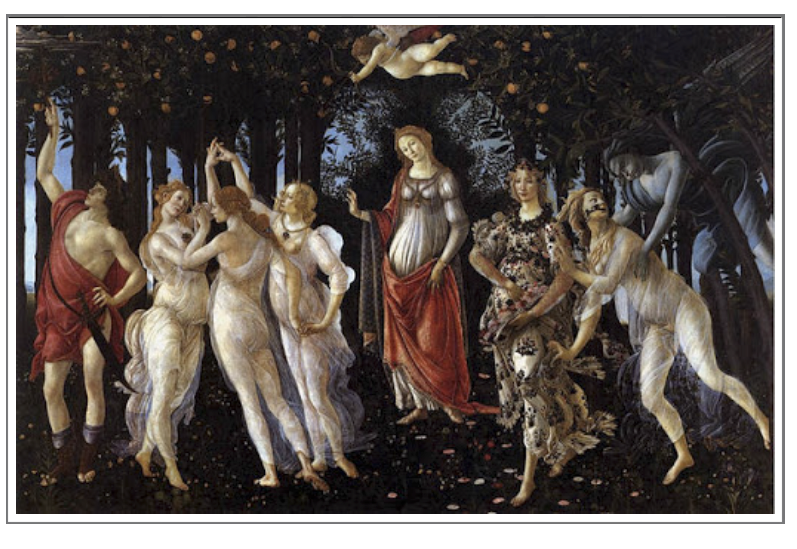

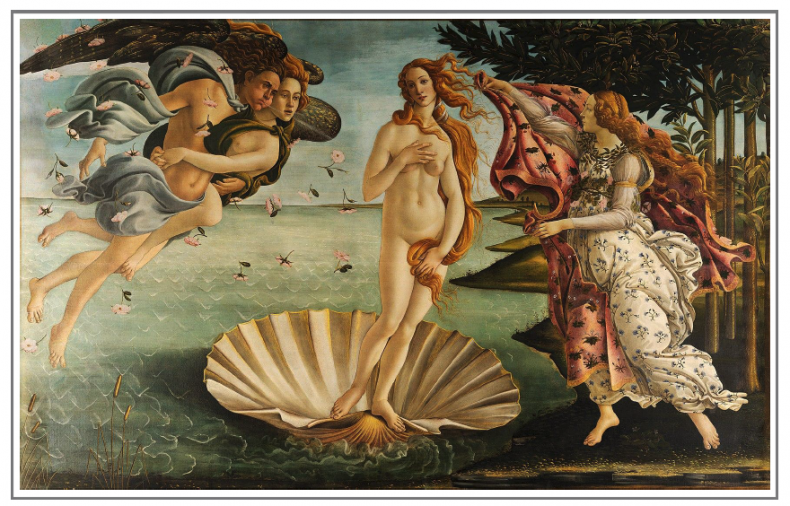

Although some critics speak more of a search for idealized beauty rather than a muse in flesh and blood, it is not difficult to recognize the similarity in many of Botticelli’s female portraits, which supports the hypothesis of the existence of an inspiring model. It is therefore believed that it is the beautiful Simonetta Vespucci who is depicted, half-naked, in the guise of the goddess Aphrodite in the “Birth of Venus” — an allegory of Love understood as the driving force of Nature; it is necessary to mention the last verse of Dante Alighieri’s Paradise: l’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle (“the love that moves the sun and the other stars)” — in “Spring” as the goddess Flora, and as Venus in the painting “Venus and Mars,” now preserved in the National London Gallery.

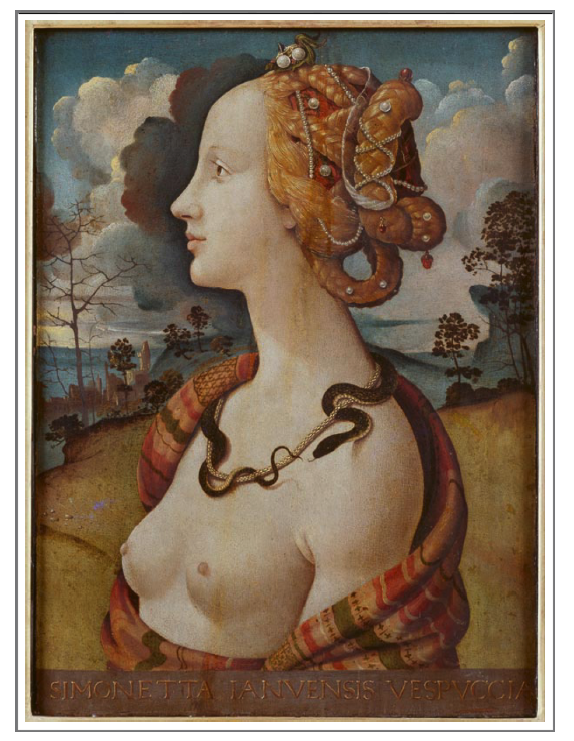

Botticelli’s obsession with Simonetta’s face, even after her death, made her an archetype of beauty with a refined and elegant air, eternalized in a timeless place, and which still today makes us associate her face with aesthetic canons of the Renaissance. If beauty, expressive purity, and formal balance are the most immediately recognizable figures of Botticelli’s art, it must be borne in mind that they still represent only a first level of interpretation of his masterpieces. The second implies a complex system of allegorical references, which refer to the Neoplatonic idea of the possibility of rising from the material world to the contemplation of the divine through beauty and spiritual love. A sophisticated symbolism is also present in the works of Piero di Cosimo, who imagined Simonetta in the guise of a topless Cleopatra caught just before the fatal bite in the painting, now in the Musée Condé in the Castle of Chantilly, accomplished in 1480, years after her disappearance.

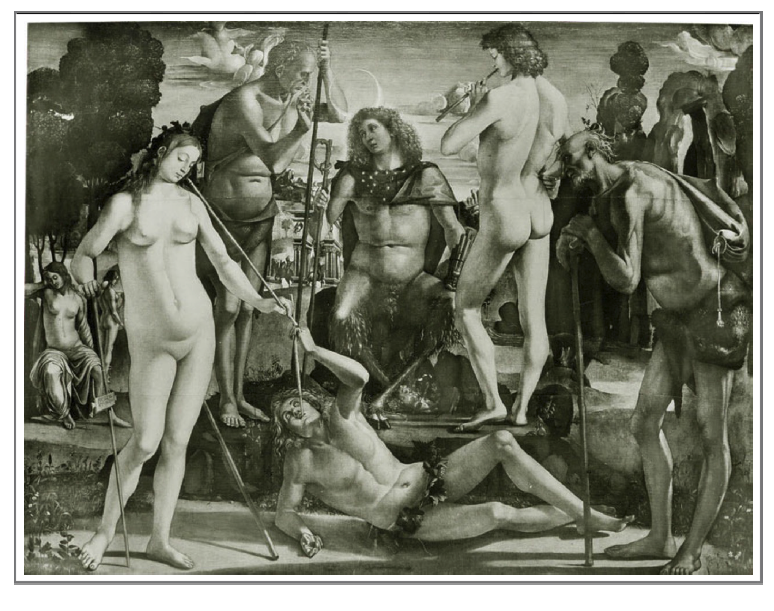

A posthumous portrait — the author, in the year of the young woman’s death, was just a teenager — and perhaps posthumous also the marble bust of the National Gallery of Art attributed to Verrocchio and many other representations, including the lost painting “The Education of Pan” by Luca Signorelli of 1490, which all testify to the emergence of a sort of cult of Simonetta in the art world in the last decades of the fifteenth century.

The truth is that we do not know of any painting that has handed down the real features of Simonetta Vespucci to us. Similarly, no document has ever been found capable of proving that Simonetta posed for Botticelli, or at least ever appeared in one of his works. The most recent criticism has now dismantled these hypotheses, considering them a reflection of a true “cult” for Simonetta Vespucci which spread in the seventies and eighties of the fifteenth century in Florence and which exerted a considerable influence also on nineteenth and twentieth-century criticism. However, this does not mean that, at the time, there were no portraits inspired by the beautiful girl: in a letter sent by Simonetta’s father-in-law, Piero Vespucci, to Lucrezia Tornabuoni, mother of Lorenzo the Magnificent and Giuliano de Medici, reference is made to an

image of Simonetta that would be given to Giuliano after the girl’s death. The fact that the portraits of Berlin and Frankfurt (excluding the unappealing lady of the Palatine) have a rather high degree of idealization and could lead to a lot of discussion about the possibility of hypothesizing that one of the two is the “image” mentioned by Piero Vespucci. But perhaps, as the art historian Stefan Weppelmann recently wrote in a catalog entry on the portrait of Berlin, “the question of whether the Berlin and Frankfurt paintings represent Simonetta Vespucci seems far less relevant than their possible role of literary images and, consequently, their intent to depict the humanistic formulation of the ideal of beauty.” Because in the end, observing these works, we see nothing but ideal women who transmit to us the canon of the beauty of fifteenth-century Florence: and it is certainly not a small thing! In many admirations, her character remains an enigma: no woman of the Renaissance was given so many awards by her contemporaries and, if we consider that she lived only seven years in Florence, this veneration appears even more exceptional. Perhaps the young Genoese woman could inspire many artists precisely because she was prematurely torn from life, granting art only the promise of eternal beauty, combined with inconsolable regret for her loss.

Removed from the corrosive action of time, Simonetta survives idealized, eternalized forever in Botticelli’s masterpieces with her gentle features, in

which her large eyes veiled with melancholy stand out, emblematic of the angelic woman coveted by the Dolce Stil Novo. One last curiosity: the church of Ognissanti, in which the mortal remains of Simonetta Vespucci rest, also houses the remains of Sandro Botticelli who, according to legend, asked to be buried at the feet of his muse. The reality, however, was probably much less romantic, because both the Vespucci and the Filipepi had their family tombs in the same place of worship, both having lived in the same neighborhood.

==============

Carl Kruse Art Blog Homepage

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Asia Leonardi on the blog include an expose of the German painter Charlotte Salomon, Action Painting, and an interview with Berlin architect Andrea Liguori.

Find me also on TED.

Though not conclusively proven it would seem that most if not all of the portraits discussed in this article are indeed of Simonetta Vespucci.

No one truly knows Maria Noel, but it would be a good bet, no?

Carl Kruse