by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

On 6 July 1907 in Mexico City, Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon was born to German parents who emigrated from Hungary. She claimed to be born in 1910, with the Revolution, with a new Mexico.

Frida Kahlo is a revolution. An artistic revolution, a revolution of thought, an overwhelming hymn to life that is born with every lively stroke of color; some approached her to surrealism, but Frida was the first to break away from this definition: “I have always painted my reality, not my dreams.” Pure energy, a living fire and an intoxicating passion, Frida Kahlo looks like a character straight out of the pen of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, small, proud, survivor of polio at six, and of a terrible car accident at eighteen that will leave her invalid, the art of Frida is born from her survival instinct. She dyes her pains with color, transforms them into beauty.

“I paint flowers to keep them from dying.”

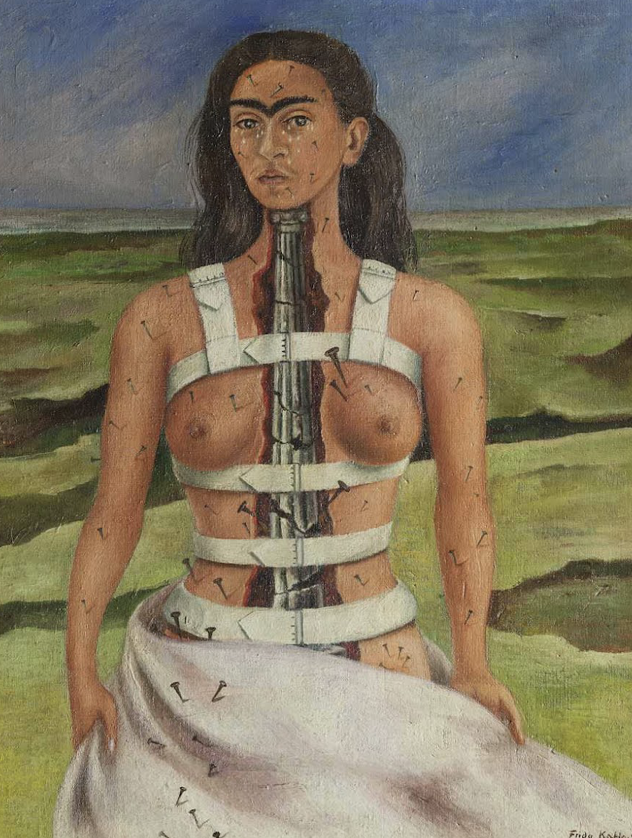

A strong, tenacious woman, a fighter: Frida is a disarming and full throttle scream, born from the awareness that you can always survive pain and that you must have the courage to be who you are, and to love yourself beyond the limits of your body. Frida paints herself crudely, in front of a mirror she observes and depicts her naked suffering with bright colors, the labor of her body, with pride, her eyes are always pointed, straight and motionless, giving the impression of probing the soul of the beholder. Facing a portrait of her, we are almost inclined to lower our heads, in front of the majesty of her figure, tense, suffering, proud.

“I lived from art, I lived from love.” A life between suffering and passion.

At the age of six Frida falls ill with polio: her right foot and leg remain deformed, so much so that Frida hides them first with pants and then with long Mexican skirts. So, if when she is little she is nicknamed by other children “Frida Pata de Palo” (wooden leg), when she grows up she will be admired for her exotic appearance.

In 1922, at the age of 18, Frida enrolled in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in Mexico City intending to become a doctor. During this period Frida is part of the “Cachucas”, a group of students who support socialist ideas of the Minister of Education, Vasconcelos, calling for school reforms; she also shows interest in the visual arts but has not yet thought of pursuing an artistic career.

On September 17, 1935, the bus bound for Coyoacàn, on which Frida Kahlo had boarded with her boyfriend, Alejandro Gomez, to go home after school, collided with a tram.

“I got on the bus with Alejandro… Shortly after the Sun train bus of the Xochimilco line collided… it was a strange collision; not violent, but deaf, slow, and massacred everyone. Me more than others. It is false to say that it makes us shocked, false to say that we cry. I didn’t shed any tears. The impact dragged us forward and the handrail went through me like the sword goes through the bull. “

Frida remains between the metal rods of the tram. The handrail breaks and goes over her from side to side. Alejandro picks her up and notices that Frida has a piece planted in her body. A man puts his knee on Frida’s body and takes out the piece of metal.

The first serious diagnosis comes one year after the accident: fractures of the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae, three fractures of the pelvis, eleven fractures of the right foot, dislocation of the left elbow, deep wound in the abdomen, produced by an entered iron bar from the right hip. Acute peritonitis, the patient is prescribed to wear a plaster corset for 9 months, and complete rest for at least 2 months after discharge from the hospital.

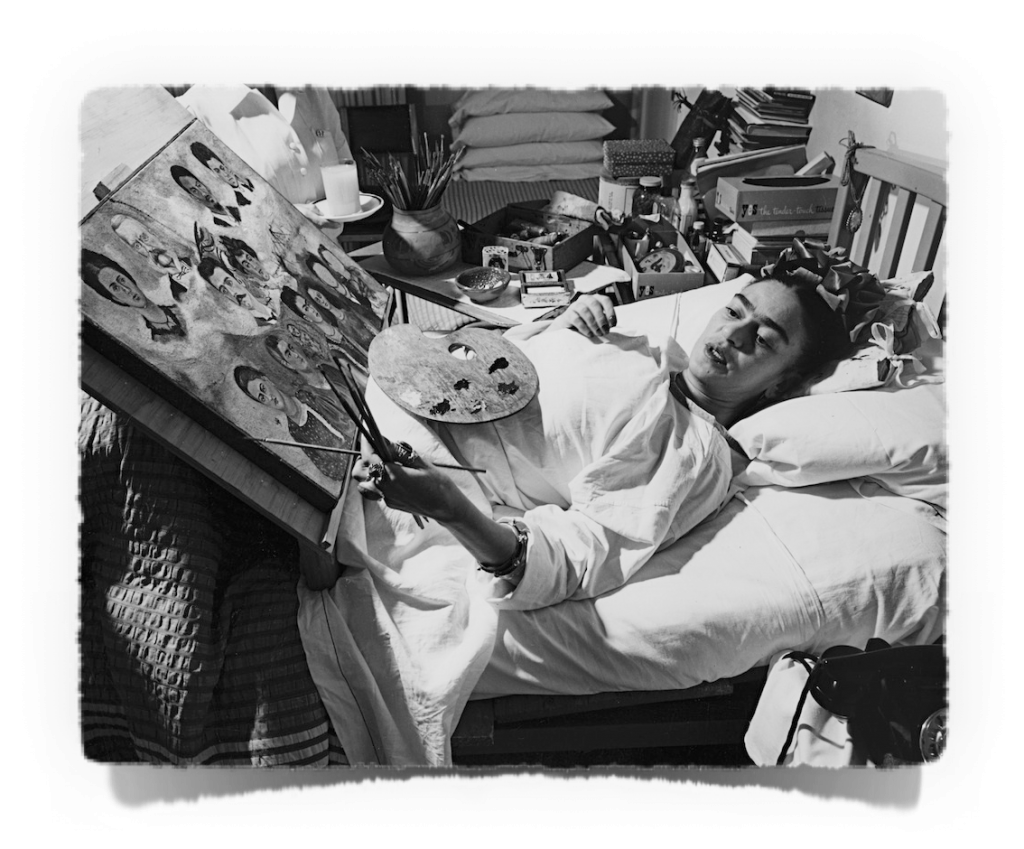

“For many years my father kept a box of oil paints, a couple of brushes in an old glass and a palette … during the period when I had to stay in bed for a long time I took advantage of the opportunity and I asked my father to give them to me … My mother had an easel prepared, to be applied to my bed, because the plaster bust did not allow me to stand up straight. So I began to paint my first picture.”

Frida’s mother, Matilda, transforms Frida’s bed into a canopy and mounts a huge mirror on it, that Frida, immobilized, can at least see herself.

Thus are born those self-portraits that remind us of her, with her eyes dominated by dark eyebrows, particularly marked, which join the root of the nose like bird’s wings: “I paint myself because I spend a lot of time alone and because I am the subject that I know best.”

With these representations, Frida breaks the taboos relating to the body and female sexuality. Diego Rivera, her future husband, will say of her: “the first woman in the history of art to have faced with absolute and inexorable frankness, in a ruthless but at the same time calm way, those general and particular issues that exclusively concern women.”

As the months passed, Frida devotes herself with growing awareness to painting. She advances slowly, produces in small doses and small formats: what her health allows her to do: “my paintings are painted well, not lightly but with patience. My painting carries within itself the message of pain. “

Only towards the end of 1927 did Frida recover enough to be able to lead a normal life despite the pain caused by the various braces, and the scars left by the operations.

In 1928 Frida joins a group of artists and intellectuals who support independent Mexican art, far from academicism and linked to the popular expression: Mexicanism, which is expressed in mural painting, particularly encouraged by the state, almost certainly for the purpose of sharing national history with a large illiterate mass.

For her part, Frida creates her own figurative language to express ideas and feelings; the world contained in Frida’s works refers above all to Mexican popular art and pre-Columbian culture; there are, in fact, popular votive images, depictions of martyrs and Christian saints, anchored in the faith of the people; moreover, in the self-portraits, Frida is almost always represented in country clothes or with Indian costume.

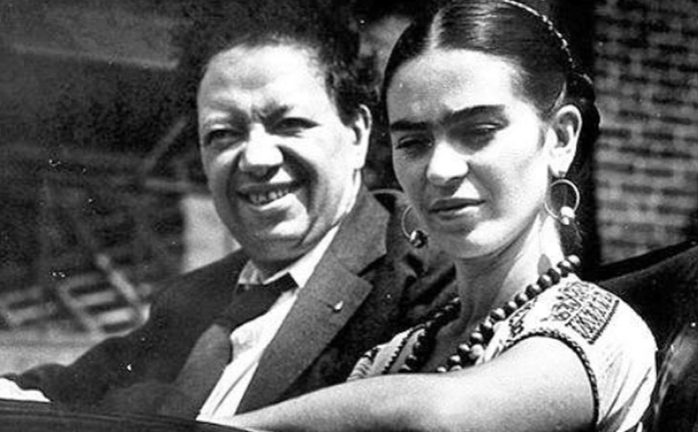

In early 1928, German Del Campo, one of her friends from the student movement, introduces her to a group of young people gathered around the Cuban communist Julio Antonio Nella, who is in exile in Mexico and who has an affair with the photographer Tina Modotti. It was Tina herself who introduced Frida to Diego Rivera: a very famous painter and muralist, even though the two had already met in 1923, while Diego was working in the Bolivar amphitheater. Of that meeting Diego remembers this girl … “she had a dignity and self-assurance that was completely unusual and a strange fire danced in her eyes.”

When Frida meets Diego for the second time, he is a heavy, gigantic man, Frida teases him by calling him “elephant”: he has already been married twice and has four children.

On 21 Agust 1929 they get married. She is 22, he is almost 43.

Due to the pelvic malformation caused by her accident, Frida is unable to carry out her pregnancies, and so, three months after the wedding, Frida has to have an abortion. In November 1930, Frida and Diego moved to the United States for four years for artistic and political reasons. In Detroit, Frida becomes pregnant for the second time, but the triple fracture of the acinus hinders the correct position of the baby. However, Frida decides to keep the baby, despite her poor physical condition and the risk. However, on July 4th she lost this baby to a miscarriage.

In 1934 they return to Mexico, Frida is forced to have an abortion for the third time and separates from Diego who, in the meantime, had had several adventures with other women, including Frida’s sister, Cristina.

Frida begins to have relationships with other men and other women and to be active politically. During the 1936 Spanish Civil War, Frida commits herself remotely to the defense of the Spanish Republic, organizing meetings, writing letters, collecting necessities, clothes, and medicines to send to the front.

In 1937, she hosted in her Casa Azul, Lev and Natalija Trotsky, who had been traveling since 1929, expelled from the Soviet Union.

In the 1940s, Frida’s fame was so great that her works were requested for almost all group exhibitions held in Mexico.

In 1943 she was called to teach at the new art school: the Esmeralda. Frida, for health reasons, is soon forced to give lessons in her home. Her methods are unorthodox: “Muchachos, locked up here, at school, we can’t do anything. Let’s go out into the street, let’s paint the life of the street.” Her students remember her “the only help she gave us was to stimulate us … she didn’t say anything about the way we had to paint or about the style, like the master Diego did … She taught us above all the love for people, she made us love popular art “.

In 1950 Frida underwent seven spinal operations and spent nine months in the hospital. After 1951, due to pain, she was no longer able to work except by resorting to painkillers: perhaps this is why her brushstroke is softer, less accurate, the color thicker and the execution of details more imprecise.

In 1953, at her first solo exhibition, set up by her photographer friend Lola Alvarez Bravo, she participated lying on a bed, the doctors practically forbade her to get up. It was Diego who had the idea of carrying the large bed, drinking, and singing with a large audience. In August of the same year, the doctors decided to amputate her right leg.

Frida is destroyed, withdrawn into herself, reflects, and writes in her diary a phrase born from this period that becomes famous: “Pies. para que los quiero, si tengo alas pa’ volar.” (“Feet. why do I want them, if I have wings to fly?”)

In 1954 she fell ill with pneumonia. During her convalescence, on July 2, she participates in a demonstration against the U.S. intervention in Guatemala, holding a sign with the symbol of a dove carrying a message of peace. Frida died of a pulmonary embolism on the night of July 13, in her Casa Azul, seven days after her forty-seventh birthday. The night before she died, with the words “I feel that I will leave you soon,” she gave Diego a ring, which was to be her gift for him on their upcoming Twenty-fifth anniversary.

=================

The blog home page is at https://carlkruse.net

Former articles by Asia Leonardi include those on Simonetta Vespucci, Charlotte Salomon, and Jackson Pollock.

The blog’s last post was “Are Memes Art?“

Carl Kruse has an account on Behance.

Frida Kahko supposedly said on her deathbed that she hoped never to come back, and after reading about her life I don’t blame her.

Sure sounds like she had an incredibly rough life.

I believe the quote referenced above comes at the end of the 2002 movie “Frida” with Salma Hayek.

Carl Kruse