Breaking the Waves: Women on Film

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

It is sincerely difficult to write about love. Attempts to do so are often vapid, overly sentimental, gratuitously flowery, or simply boring. We have all written about love; in letters, poetry, texts, emails, journals – we have all thought ourselves to be the most intuitive of poets with visions of love and life more fruitful and honest than any of our predecessors. This is because love is an all-encompassing experience; it blinds, weakens, strengthens, feeds, and drains all at once. We cannot see love when we are inside it, and this can stunt us, creatively speaking. So, when someone makes a work that looks into love, as though from the outside gazing in through a window lit up in the dark, it is a marvelous and admirable feat.

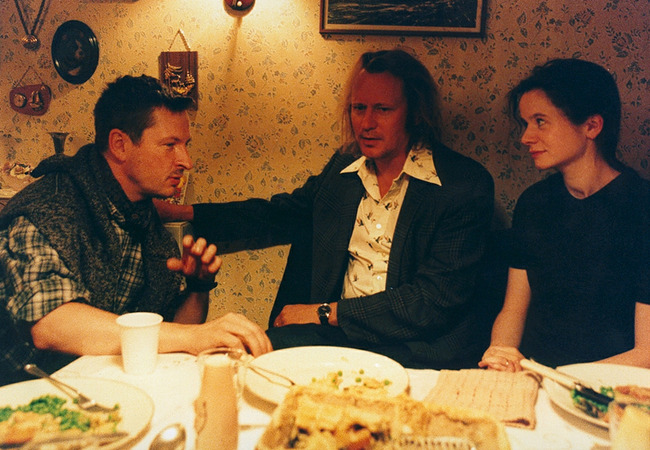

Breaking the Waves is Lars von Trier’s fifth feature film, released in 1996 as part of his ‘Golden Heart’ trilogy, so named because the three films within this compilation (Breaking the Waves, The Idiots (1998), and Dancer in the Dark (2000)) all contain within them heroines who, despite their devastating misfortunes and tragic encounters, remain naively ‘golden-hearted’ right up to the end. Breaking the Waves’ heroine, Bess McNeill, played by Emily Watson in her breakthrough role, is perhaps one of the most wonderful female characters I have ever seen on screen, not only for her inimitable onscreen chemistry with Stellan Skarsgard (who plays her husband, Jan). She has an abandon, a childish glee and freedom that pervades the atmosphere of the film with nostalgia and beauty. Bess loves with her whole self, a self that is defined by her unwavering faith to God and her achingly innocent perceptions of romance, a self that seems so fragile, so virtuous so as to not belong to or be deserved by this world. When one watches Bess glide about the screen, giggling and dancing and running and making love, one feels a guilt, a shame that one so pure as Bess should be so crushed by the horrors of the world. There is a Bess in us all, a golden-hearted soul that was trampled by the boots of responsibility, work, money, debt, heartbreak.

Bess was Lars von Trier’s first female lead, and she was a stark contrast not only in gender but in temperament to von Trier’s prior male protagonists, whose idealist natures were brought to ruin oftentimes as a result of femme fatales of some variety or another. Female protagonists are a difficult thing to get right, it seems; the critics and scholars have much more of a taste for shooting down the depiction of a woman or female-identifying protagonist on screen than a man, lest he be overtly of the distasteful variety. Bess was no different – soon after the release of Breaking the Waves came the claims of misogynistic intent in the portrayal of her martyrdom. Such words as ‘problematic’ and ‘oppressive’ began to be flung about. Now, I’m not diminishing the widespread critical acclaim of the film – it was arguably Lars von Trier’s most highly awarded and celebrated film, winning the Grand Prix at Cannes in 1996, Best Motion Picture in Drama at the Golden Globes in 1997, and continues to be beloved by many arthouse filmgoers and critics alike. But I think it interesting to enquire into the qualm of representation of female or female-identifying characters on screen; how do we get it right? Can we even get it right, or are its parameters too tight, so tight as to be suffocating, restricting, stifling to a writer or filmmaker? Are our desires for the ‘correct’ female protagonist too extreme? Which female characters do we deem to be ‘correct’ and ‘unproblematic’?

Well, if I were to refer to the perspectives of charity website ‘Girls Empowerment Network’, I would see the following list of so-called ‘empowering female leads’. Granted, this is a list for ‘girls’, but, still, I found this list to be quite enlightening: Hermione Granger (Harry Potter), Merida (Brave), Imperator Furiosa (Mad Max), Nakia/Okoye/Shuri (Black Panther), Mulan (Mulan), Storm (X-Men), Elle Woods (Legally Blonde), Princess Leia (Star Wars), Starr Carter (The Hate U Give), and Katherine Johnson/Dorothy Vaughn/Mary Jackson (Hidden Figures). Now, I can’t speak to all these characters, partly because I haven’t seen all of these films and also because this article isn’t about how ‘empowered’ these respective characters are. But I’ll just comment briefly to try and contextualise my misgivings about the perspective that Bess is a less ‘empowered’ woman than any of those on this list.

We’ll start with Hermione. I grew up with Hermione, watching and reading the Harry Potter series from a very young age and still thoroughly enjoying the films today. I understand the sentiment that this article is attempting to propound by putting Hermione on this list, but I’m afraid I have to fervently disagree. One, because Hermione’s character in the films is oftentimes COMPLETELY defined by her relationship with men, and the conflicts that arise as a result of these relationships. Hermione comes between her two best friends, Ron and Harry, because Ron is in love with her and believes her to be in love with Harry in the film(s) The Deathly Hallows. In part 1 of this two-parter, the smell of Hermione’s perfume lures in a band of snatchers. In the film The Goblet of Fire, Hermione is depicted as pining after a love-potion in an odious moment where all the girls in potions class walk towards the love potion in a sickeningly fawning manner. At the Yule Ball, Hermione’s arrival in her elaborate pink dress is lingered on in a most obvious manner, as if to say ‘look, Hermione doesn’t always dress in jeans – she’s a woman too!’.

What is Bess McNeill to us, now? Why are people so afraid of a woman using her sexuality as a form of payment, a form of sacrifice? If Bess had, for example, given away all her money and belongings when her tragically paralysed husband, Jan, told her to, then I’m sure no-one would bat an eyelid. Or maybe it would just be a different complaint, one about female empowerment in the business world, or something. We can’t pretend that bad things don’t happen, that bad people aren’t out there, that young women don’t fall prey to bad decisions due to coercion and sense of duty. I know that I have had tendencies like Bess, to please people and do what they ask because, for some reason, I feel I ought to, like I owe it to them and don’t owe anything to myself. Breaking the Waves does not suggest that a woman should do such things; rather, it explicitly reveals the pain and suffering that comes as a result of how young women are raised. Religion defines Bess’ lived experience, in a village where women cannot go to funerals, where men dominate the landscape in dark and insidious ways. Bess is just a product of her surroundings, a lonely girl whose only purpose is to serve, to serve her Lord God. So when she finds love, a beautiful, effortlessly tender love, what can she do but give herself to it, just as she has given herself to others her entire life? Bess’ power is her womanhood, her sexuality, her devotion to love and faith. We should not criminalise her or damn her for being who she is. Bess is simply a person who lived in the wrong time, the wrong place, the wrong world. Lars von Trier was not misogynistic or wrong for depicting a character like Bess, in fact, he was probably right to do so; he made us feel for Bess, hold sympathy for her, laugh with her, wish the best for her. After all, women such as Bess do exist, even if we’d prefer to pretend that they don’t. And that’s just how it is.

==========

The Carl Kruse Arts Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.net.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Hazel include A Series on Lars von Trier, Part 1, Giorgio Morandi, and A Positive Spin on Hustle Culture.

Carl Kruse is also on Buzzfeed.

Totally agree and I’m a 68 year old feminist. Some of the most puritanical outcries is that she resorts to sex work which in some ways can empower women.