by Rosie Lesso for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

Art and politics have a closely intertwined relationship going back millennia. But it is only in the past 100 years that artists have embraced art as a form of political protest, one that can educate, inspire or instigate change. Known as ‘activist art’ or ‘protest art,’ this fusion of art and activism is daring, provocative and confrontational, attempting to speak for the voiceless and marginalized, challenging political leaders, institutional managers and individuals to make change. In our social media driven society the impact of activist art is more relevant than ever, able as it is to reach large international audiences with pressing issues of the day, such as climate change, LGBTQ+ rights, feminism, racism and the abuse of power.

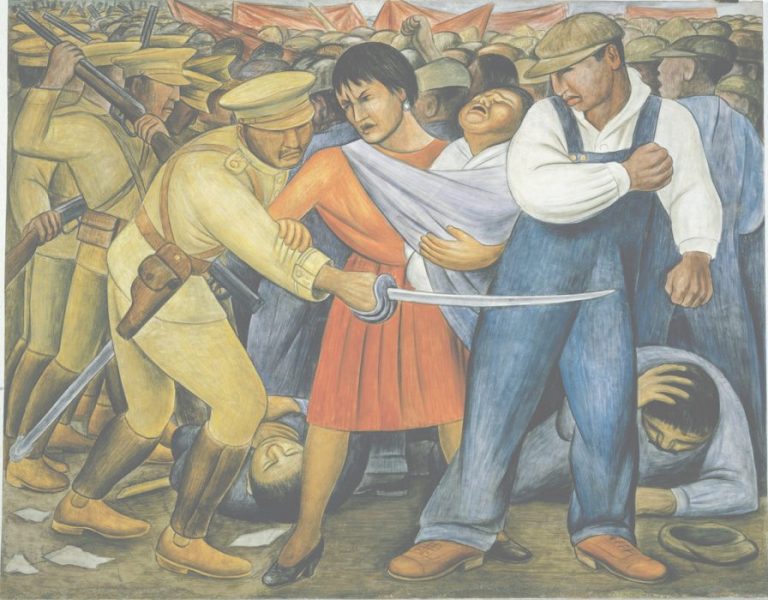

Diego Rivera, The Uprising, 1931, image via MoMA and The Observer

The boundaries between acts of public protest and performance art are porous and blurred, so it can be hard to trace back a clear historical narrative for today’s activist art. But some of the most influential artists to first experiment with a fusion of politics and art were the German Dadaists, whose ridiculous, nonsensical poetry and performance art was fueled by angry defiance against the barbarism of the First World War. In the 1920s and 1930s the Mexican Muralist Movement brought their political agenda out into the streets with sprawling public murals that condemned the ruling class, capitalism and the church, calling for Mexico’s ordinary workers to lead the country into the future. Picasso’s huge, frieze-like Guernica of 1937, was a more harrowing message to the public, conveying the horrific brutalities of the Spanish Civil War with broken, dismembered bodies and screaming, tortured faces.

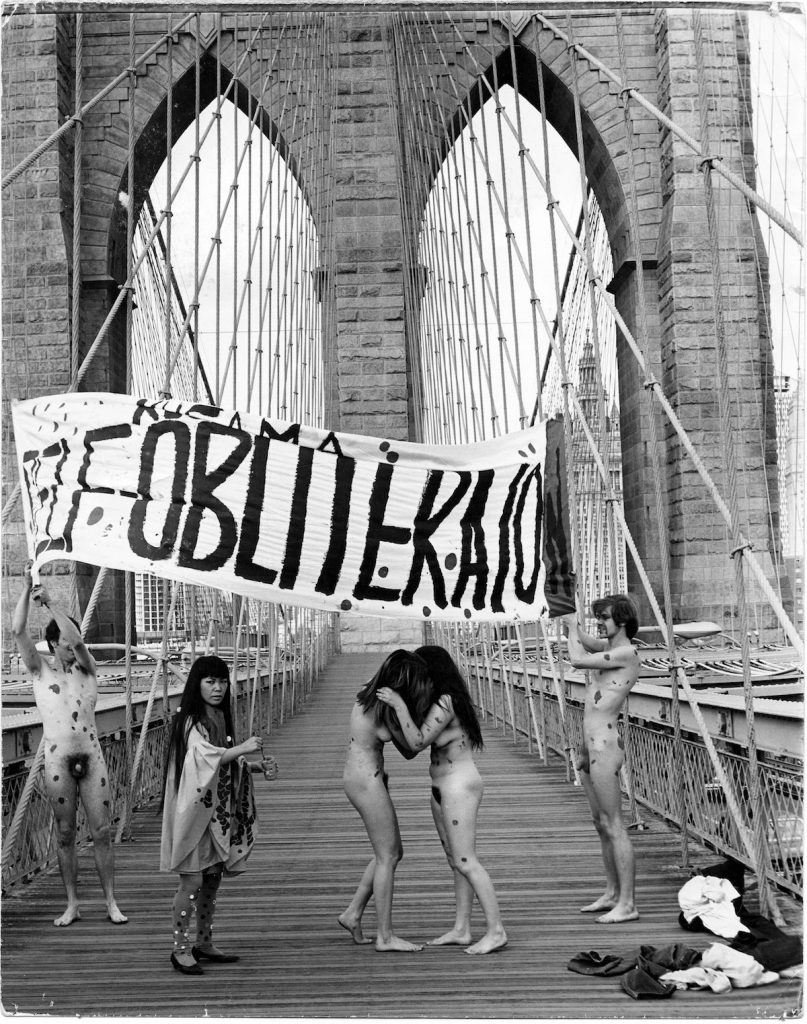

Yayoi Kusama, Anti-War, Brooklyn Bridge, 1968, image via ARTnews

Anti-war sentiment continued through the 1960s and 1970s as artists raged against the Vietnam War with happenings that reflected the dawn of the hippie era. Yayoi Kusama tried to kill hate with love, staging naked protests on the streets of New York, while Chris Burden deliberately wounded himself to bring home the realities of unseen suffering. Other sociopolitical issues that found their way into artistic forms of protest during the 1970s and 1980s are battles still being fought today, sometimes by the same voices that arose during that time. These include feminist artists who rejected the gender biases of the past, and ethnically diverse groups who continue to rally against marginalization.

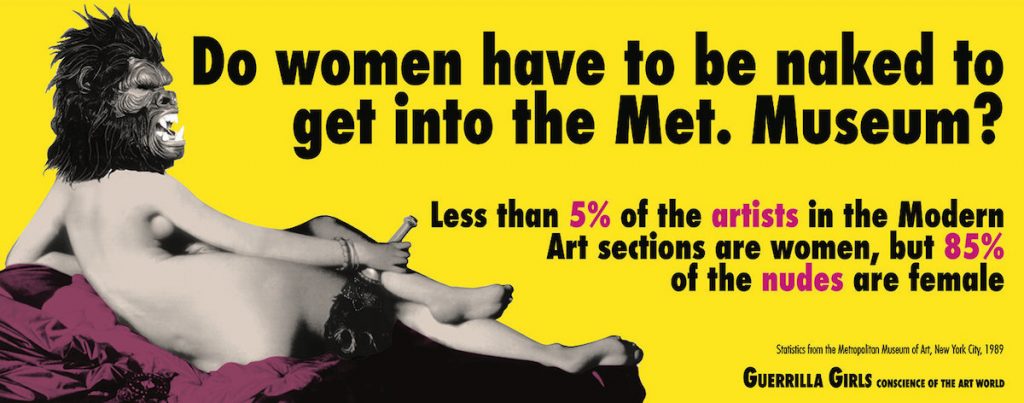

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989, image courtesy Guerrilla Girls

One of the most outspoken groups of this era were The Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous, all-female group based in New York who aimed to subvert what they saw as the “male, pale, stale, Yale,” biases of the art world with a series of jarring and satirical poster campaigns. Wearing gorilla masks to conceal their identities, they pasted posters bearing embarrassing statistics across the streets of New York throughout the 1980s, challenging art institutions to address sexist and racist discrimination. Still an active group today, The Guerrilla Girls continue to create posters, performances and videos highlighting wider societal inequities, embracing Instagram and YouTube as further platforms for the dissemination of ideas. As well as educating the wider public about art world discrimination, their campaigning has played an active and important role in the rising inclusivity of museums and galleries worldwide.

Pussy Riot, Punk Prayer, 2012, image via TV Guide VG

The Guerrilla Girls undoubtedly had a profound impact on the feminist Russian protest group Pussy Riot, who first stormed onto the international art scene in 2012. Dressed in balaclavas and brightly colored clothes, they staged a series of pop-up events across Moscow directed against Putin’s regime, speaking against the segregation of women, racially diverse groups and LGBTQ+ individuals. Their most notorious art protest, Punk Prayer, was staged at Moscow’s Christ the Saviour Cathedral in 2012, where they performed an obscenity-laced song highlighting their country’s institutional sexism and racism and calling “Holy Mother, Blessed Virgin, chase Putin out!” Posted online, their stunt quickly went viral, before making its way to the enraged Russian authorities. Accused of hooliganism and religious hatred, several members were imprisoned after the event, but their activist stunt had already earned them an international following, raising a warning to the world about the destructive impact of Russia’s government.

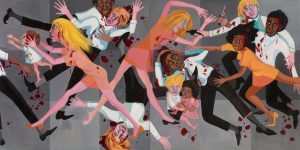

The American People Series #20: Die, 1967, image via The New York Times

Given how raw racial politics continue to be, it is perhaps no surprise that many protest artists have chosen to address this troublesome issue. African-American artist, activist and educator Faith Ringgold’s imagery since the 1970s has been jarring and influential. Her violently direct painting The American People Series #20, Die, 1967, addressed the brutality of New York’s 1964 race riots, highlighting the violence of a racially divided America with a universal language that is as relevant today as it was in the 1960s. Ringgold deliberately exposed the violence of the events, noting, “If [the media] did show a photograph or a picture of any kind of riot, they never showed the blood…So I wanted to make sure that I put the blood in there, because I knew that blood meant death, and that’s what happened at those riots.”

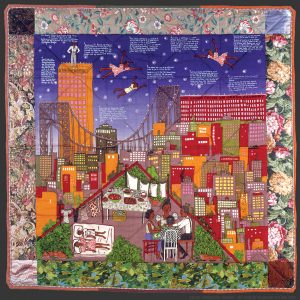

Faith Ringgold, Tar Beach #2, 1990

In the 1980s Ringgold turned to the unlikely medium of story quilting, embracing this uniquely feminine language as a tool to present a more unified, hopeful vision of life for African Americans. The much-celebrated stories and imagery of her ‘Tar Beach’ quilts of the 1990s have more recently been expanded by Ringgold into a best-selling children’s book celebrating the power of imagination, whose goal is to inspire a new generation of young people about acceptance and hope.

Marc Quinn, A Surge of Power, 2020, image via RTE, more here.

When Black Lives Matter protests raged across Europe and the U.S. earlier this year following the tragic death of George Floyd, a whole arena of artists responded with pop-up performances, artworks and events. One of the most memorable was by British artist Marc Quinn in Bristol; when a group of protestors pulled down the statue of a former slave trader and left an empty plinth in its wake, Quinn produced a bronze statue of British BLM protestor Jen Rein and installed it in its place, titled A Surge of Power, 2020. Some criticized him of opportunism, while others praised his ingenuity and kinship with the cause, even if the statue was subsequently removed by local authorities. But Quinn’s collusion with protestors in this work is an important part of the worldwide debate surrounding public art monuments, with many asking whether it is time for monuments of problematic figures from the past to be removed and replaced (See other Carl Kruse blog posts, Statues and Monuments, and Columbus Beheaded.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995, image via Public Delivery

Like Quinn, Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei is another artist who has staged many well-publicized stunts since the 1990s, most frequently directed at the oppressive nature of the Chinese government. One of his most publicized projects involved dropping a valuable ancient Chinese urn in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995, to signify his anger at Communist China’s erasure of cultural memory. More recently, Straight, 2012, was made in response to the tragic collapse of a school in China during an earthquake which killed 5,000 children. Ai spent four years making this work, gathering a huge mass of broken reinforcement bars from the building’s wreckage and bending them into a series of wave-like forms to echo the motion of the earthquake. Ai’s tragic memorial to this horrific event was also deeply embarrassing for the Chinese government, highlighting what Ai saw as blatant corruption, negligence and needless suffering brought about by the building’s poor construction.

BP or not BP?, Trojan Horse political protest outside the British Museum, 2020 image via Trebuchet Magazine

The role institutions play in climate change is another hot topic for today’s activist artists, and the activist theater group BP or not BP? is one of the United Kingdom’s most influential to emerge in recent times. Earlier this year they amassed a large gathering outside the British Museum for two full days to protest against BP’s sponsorship of the exhibition Troy: Myth and Reality. With them they brought a four-meter-long Trojan horse hiding protestors inside, while they projected a light display onto the museum’s façade reading “BP Must Fall.” Described as a “creative takeover,” the event pushed for the British Museum to sever ties with the multi-million pound oil-company. As group member Sarah Horne pointed out, “For too long, the museum has sided with its mega-polluter partner rather than the communities it is meant to represent, many of whom are already experiencing the intensifying impacts of our changing climate.” The attention-grabbing antics of this anti-oil campaign group have already persuaded prominent arts institutions to sever ties with BP, including The Royal Shakespeare Company, Tate Britain, The National Theatre and The National Galleries of Scotland, proving some arts institutions are more willing to work with and be influenced by activist artists than others.

Kara Walker, Fons Americanus, 2019, Tate Modern, (detail). Photo: © Tate (Matt Greenwood), image via Tate Modern

Tate Modern (for a visit there and commentary check out our post here) chose to turn towards, rather than away from its past when they invited African American artist Kara Walker to create a Hyundai Commission for the huge Turbine Hall in 2019. Her totemic water sculpture Fons Americanus was designed as a parody of the traditional Victorian water fountain, filled with grotesque stories of exploitation related to the history of slavery. Water here becomes a potent emblem of the transatlantic slave trade on which so much of Britain was built, gushing through violently contorted, caricatured figures as a brutal reminder of the horrific past.

It is no accident that this rising tower is sheet-white, a jarring reminder of the violence that constructed white colonialism, but there is also a nod to here to the whiteness of the sugar industry in which Henry Tate built his empire. Although slavery had been abolished by the time Tate was making his name, the sugar industry before him was entirely reliant on the grueling work of slaves. Tate Modern has openly acknowledged this past, writing, “it is … not possible to separate the Tate galleries from the history of colonial slavery from which in part they derive their existence.” But working with artists and bringing the past out into the light allows a vitally important rewriting of history to take place, one which can lead towards a more inclusive future through the power of art.

============

Carl Kruse Art Blog Homepage

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

The last post was on Andrea Liguori. The one before that was on Steve McCury.

Carl Kruse has another old blog here.

Always have admired that mural from Diego Rivera and happy to run across it here again. Cheers Carl Kruse.

I see all art as protest – mostly against reality.

Matthias, perhaps. For me art is what reality could or should be in ways that we as observers we would not clearly see without the help of the artist.

Carl Kruse