by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

Tim Lapetino’s book The Art of Atari is a celebration of the visual worlds that emerged from Atari’s mission to market their video games. It is also a compendium of a certain time, the nascent culture of video gaming. An unavoidably nostalgic book – one flicks through and is brought into the images, made to ponder, made to relive distant memories. It is now that enough time has passed that a cultural paradigm can be seen and explored in its pages.

The reason why The Art of Atari is so successful amongst its followers is because Lapetino has struck a wonderful balance between image and text. Out of curiosity, I once picked up a book called A Study of Toys. It was a deceptively long-winded book that I did not finish, considering it could be held in my hand. The book’s cover was a mute red and the author, I forget the name, was printed in leaf-gold on the spine. It reminded me of a late Victorian publication – tiny words, much writing on a page. Somehow, as you may expect, the essence of what a toy is, means, or even celebrates, didn’t quite fit in the form presented.

Logo of Atari, Sunnyvale, California U.S.A.

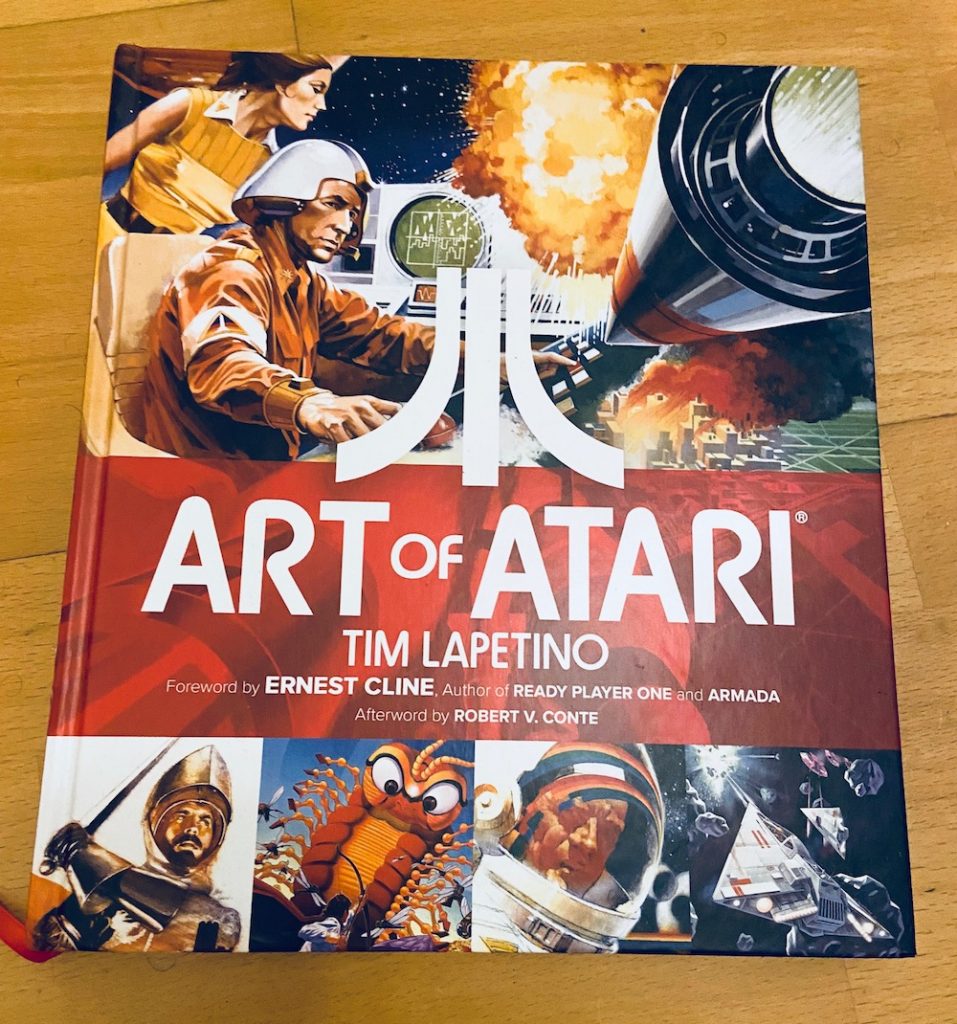

It is that the gloom, even solemnity, of that dark print belied the content of the book. A toy gladdens the heart in some inexplicable way, a bridge to wonder and play. Where but in the image of some old toy does this fact ring true? Lapetino’s book is charged with this sentiment. Of course, it is no mere picture book. Respect could, perhaps, be paid by these emotionally charged images alone, but a little text and some history serves to contextualize this world. This is why it is not only a nostalgic book but a celebration of a culture. The cover centers itself with the bold Atari symbol while images of classic games revolve around the unchanging center.

A copy of Art of Atari on the floor of the Carl Kruse office. Gift from Angelo Cioffari.

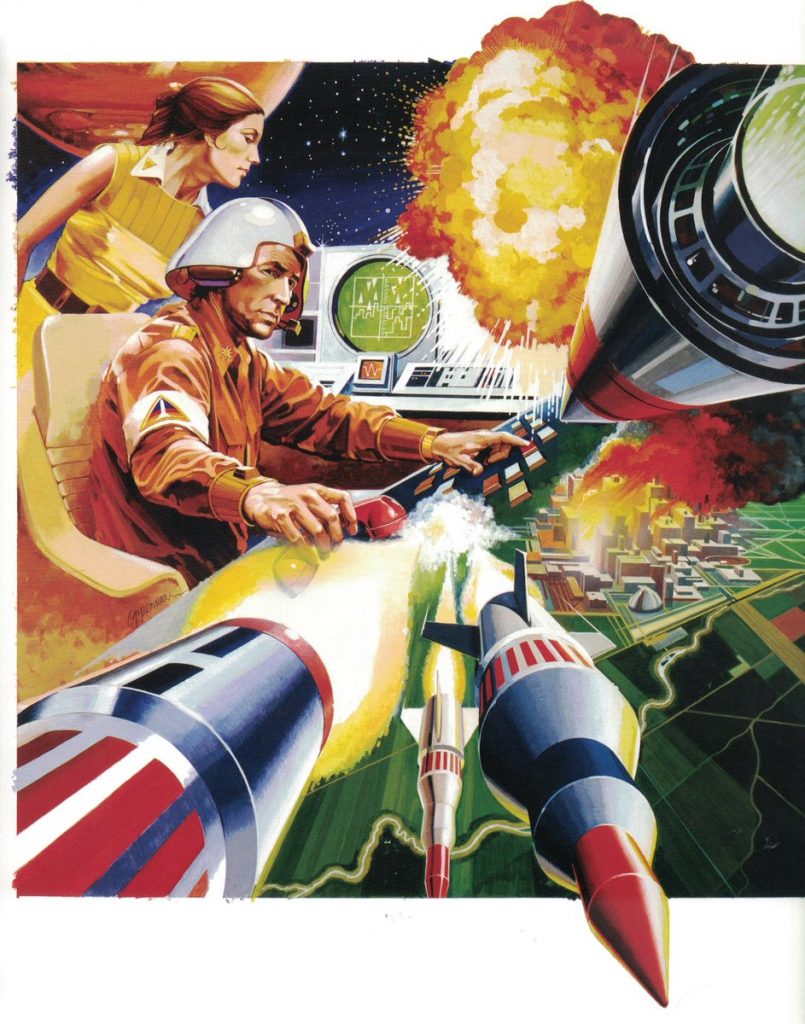

On to the art. The art of Atari was functional. The media surrounding an Atari game was not decked with screenshots of game play but described with sentences hoping to draw in a viewer’s interest. The art, then, was crafted for the market. If the imagery captured the heart, then so much luck for the company. Atari was special in that it had artists internally working for them – and we can draw the comparison with early twentieth century illustrators and painters working commission for advertisements – much of the work now coveted and esteemed.

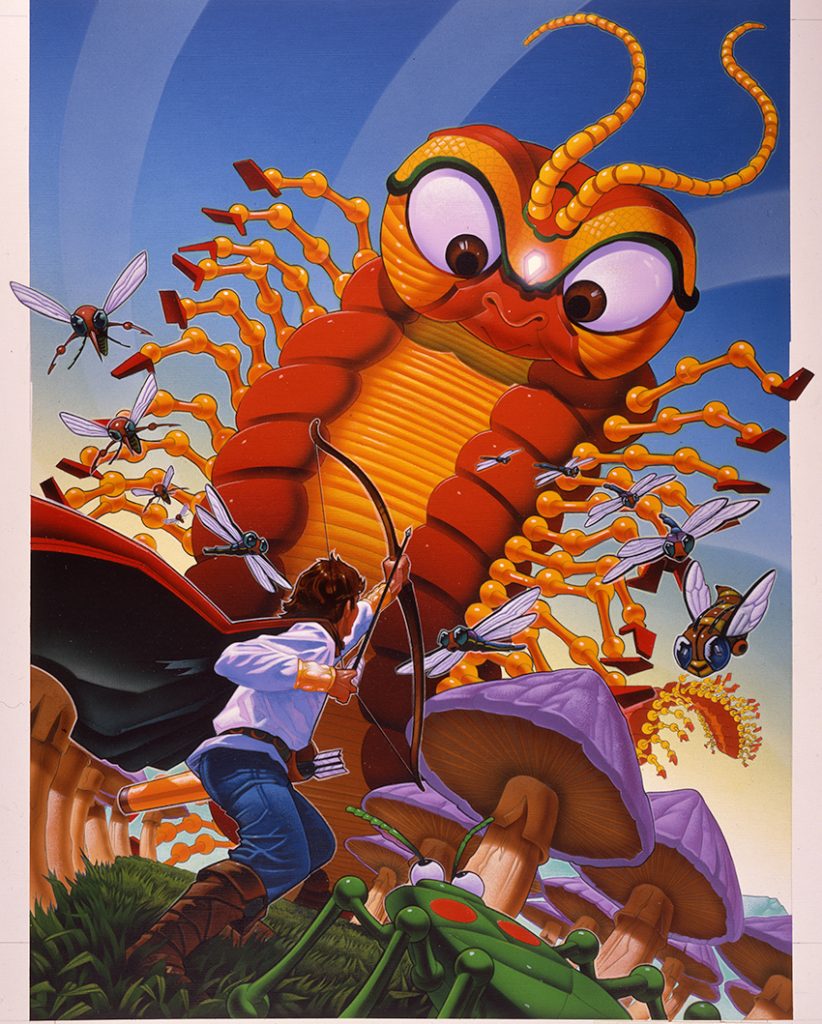

This in no manner dampens the craftsmanship of the art. The art was a companion to the game, and artwork for a video game was new aesthetic territory. The artists employed under Atari, such as Cliff Spohn, Susan Jaekel and George Opperman, gave a new distinctive visual vocabulary to Atari’s games – along with the iconic company logo. This new aesthetic helped to steer buyers in Atari’s direction, but it also served as an imaginative directive. It is an incredible thing that the mind can pick up a narrative out of the most abstract shapes – for example, a triangle following a square. Likewise, the artwork of Atari was to match the pixelated abstract games with an imaginative foreground; players don’t see a pixelated duck, they see a dragon.

Artwork for the ATARI game “Millipede.”

The stylistic devices of the artwork, the subtle detail of perspective and attractive colors, forged a language with which to express these strange excitements exacted by game play. It was the infancy of home video gaming that provided this new space to experiment artistically, and what someone takes into their home had to be of some worth. The artwork for Atari games accepted a challenge of individually crafting each game’s image to a high standard, and the art had to endow the abstract geometries of actual game play with an emotional attachment both in and outside of the game. The particularity of each artistic design was a potential particular world that consumers would bring into their homes.

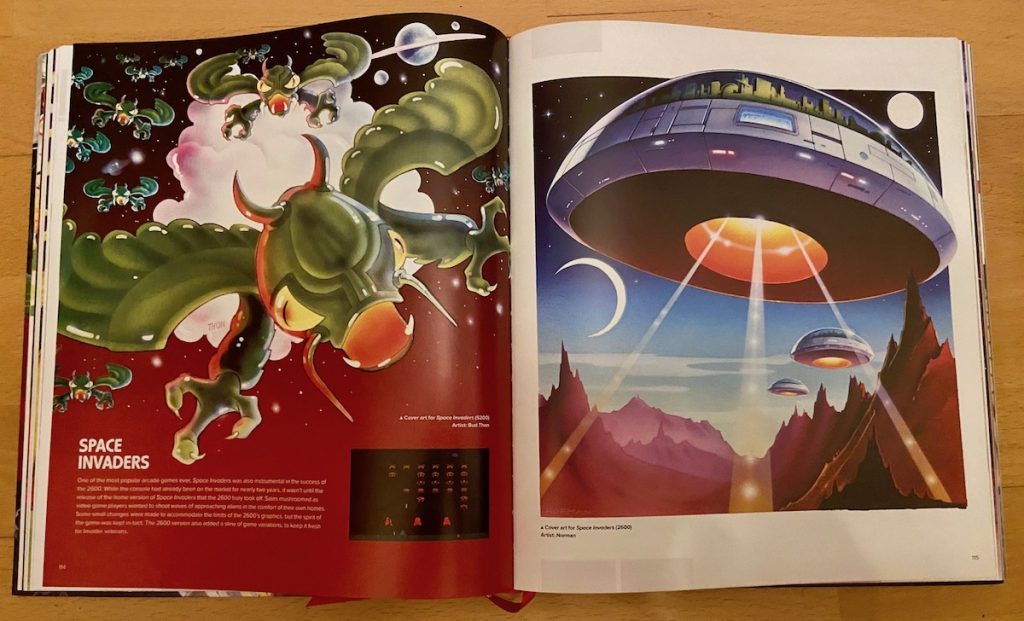

Artwork for the ATARI game “Space Invaders.”

The artists rarely, if ever, actually played the games. Most often, they had a loose understanding of the idea of the game, and after that, the concept was theirs. Tim Lapetino cites the artwork of Atari as one of those prime movers which sets the gears turning, which in his case, was a career in graphic design. For surely as the romanticism of the art wears off to a tinge of nostalgia, one begins to inspect the art from an entirely new perspective. The design, the ability to conjure images to match abstract ideas – a concept.

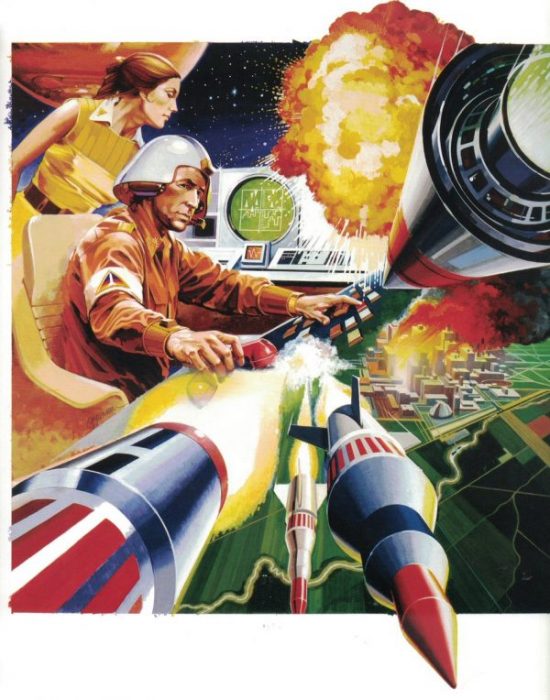

Artwork for the ATARI game “Missile Command.”

For this was implicitly the message of the art of Atari. It is possible to create, and in that creation, define an experiential activity. The ability to prove the likeness of the art to the game serves as an example in conceptualizing which can enlighten sensitivity to other facets of experience. This is not to say that all the concept art of Atari perfectly reflected the game. I’ve now heard a few people say that the leer of the pirate above the swell of waves has no particular agreement with the squares of flagship. In cases such as these, the effect is comical hyperbole.

Tim Lapetino’s book, then, unearths the mission that inspired this memorable art. The retrospective glance gives a unity to this cooperative effort to not only sell games, but to create a lasting cultural paradigm. However unified the vision now seems, it is far from obvious why a game comprised of simple geometry should be endowed with companionable art until Atari took the decisive step. It is difficult to unsee the connection. The logical progression of video games has nullified the need for such intricacies between art and the game, for such command of the imagination to link the two worlds. Lapetino’s book is drawing attention to something which is now taken for granted: the investment of imagination and emotion which is part of the gaming experience. Atari brought into the home enduring symbols which were shared by a generation of gamers, laying the foundations for the interactive and immersive spirit that the progression of gaming has supplied.

=============

The blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.net

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Fraser Hibbitt include Thinking About Realism and the Museum of Old and New Art.

The blog’s last article was the Legacy of the Satyr.

You can also find Carl Kruse on fstoppers.

Such a beautiful trip down memory lane.

Glad to see another fan here! 🙂

Carl Kruse

I just ordered a copy on Amazon. Thank you for this article.

Thank you for stopping by Tobias and happy you also are a fan of the art of Atari.

Also many thanks for your kind words.

Carl Kruse

Oh hey! Where’s the bat from ADVENTURE! Or the bi-planes from COMBAT? 🙂

I spent many hours playing both of those Atari games.

Carl Kruse

I had to google THE ART OF ATARI and my hair stood up as I watched all of the images of the games scroll by.

I had a similar experience. A time machine to another, perhaps simpler, era.

Carl Kruse

Atari’s art often transported me further than the games themselves. Thanks Kruse.

I hear you. And may not be the case for many of us? Thanks for stopping by.

Carl Kruse

All before my time, but loved learning more about Atari and its art.

Cheers Akiko! And thanks for stopping by.

Carl Kruse

Love, love, love the art of Atari.

I love, love, love it too. 🙂

Carl Kruse

One giant love fest here for the art of Atari. 🙂

Another ATARI lover here. Was sad when they didn’t make it. If anyone was deserving of staying alive it was them.

I wholeheartedly agree Sir Sushi.

Carl Kruse

Always loved the Atari artwork as a young boy. And now I see that I still do.

!!! ATARI !!!

Love, love, love the Atari artwork.

Wow. Atari. Thank you.