by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog On 6 July 1907 in Mexico City, Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon was born to German parents who emigrated from Hungary. She claimed to be born in 1910, with the Revolution, with a new Mexico. Frida Kahlo is a revolution. An artistic revolution, a revolution

Category: Activist Art

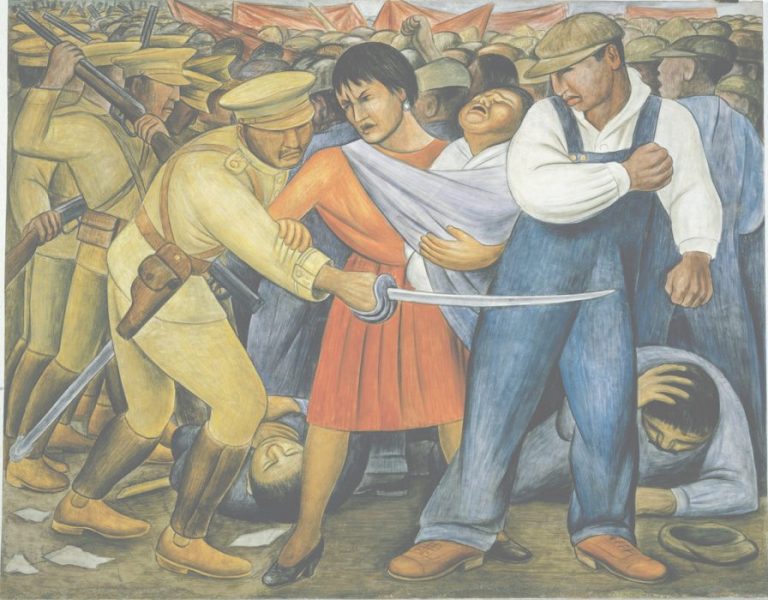

Activist Art – Art as Protest

by Rosie Lesso for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Art and politics have a closely intertwined relationship going back millennia. But it is only in the past 100 years that artists have embraced art as a form of political protest, one that can educate, inspire or instigate change. Known as ‘activist art’ or ‘protest art,’