by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog David Lynch’s work in both television and film mesmerised his viewers. With originality, a purity of vision, lovers will be matched by detractors. That is no bad thing – not in the superficial ‘any attention is good attention’, but in the challenge it poses. Stop Making

Category: Film

Landscape Cinema: An Introduction

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Without consulting a reputable source that might satisfactorily define what ‘Landscape Cinema’ might be, I am left to define it myself. Alone, in suburbia, the low drone of midweek traffic humming through my windowpanes, I am to consider what I mean when I designate a

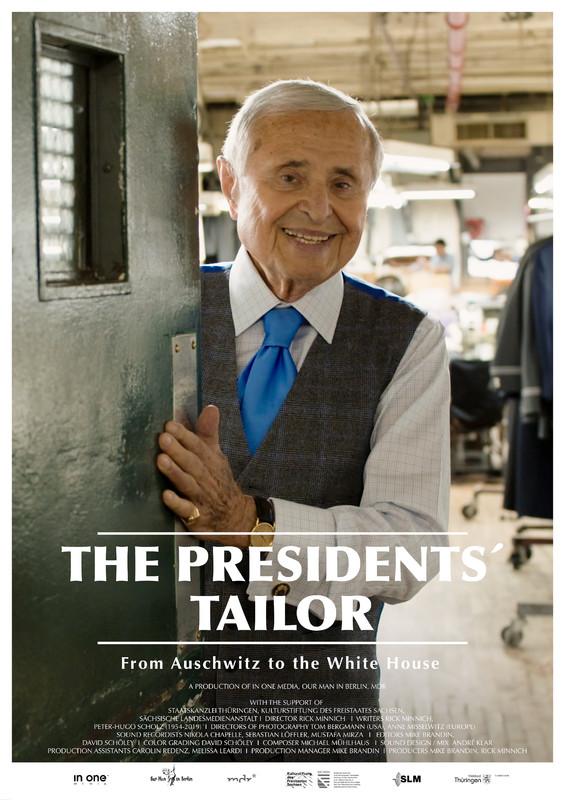

World Premiere of “The President’s Tailor”

by Carl Kruse Friend of the Carl Kruse Blog, Rick Minnich will be celebrating the world premiere of his latest film “The President’s Tailor” as part of the Jewish Film Festival Berlin-Brandenburg. The screening takes place at the Bundesplatz Kino in Berlin on June 19th at 20:30. Blog followers and friends will gather with Rick

A Series on Lars Von Trier, Part 2

Breaking the Waves: Women on Film by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog It is sincerely difficult to write about love. Attempts to do so are often vapid, overly sentimental, gratuitously flowery, or simply boring. We have all written about love; in letters, poetry, texts, emails, journals – we have all thought

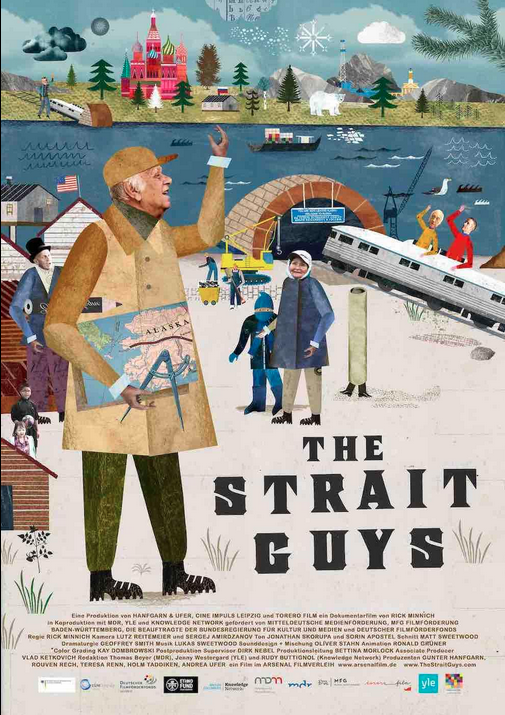

The Strait Guys Film at the Global Peace Film Festival

by Carl Kruse Filmmaker and friend of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog, Rick Minnich, cordially invites you to the closing night screening of the documentary film ‘The Strait Guys’ taking place at the Global Peace Film Festival on Saturday, September 23, 2023, 7:30-9:15 PM, at Crummer Auditorium, Rollins College, Fairbanks Ave. & Interlachen Ave., Winter

A Series On Lars Von Trier, Part 1

Part 1: A Brief Discussion of Dogme 95 by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog There is a pristineness characterizing the modern film scene. I do not mean a pristineness or cleanliness of character, theme, or narrative, necessarily, but rather of the visual. Films, and other recorded media, have become indescribably high-quality,

In Memoriam: Vangelis

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog The Greek composer and musician Evangelos Papathanassiou passed away in Paris recently. Better known as Vangelis, the award-winning musician and beloved film-score composer. Obituaries and the programs of his life abounded against the fact. A career of over fifty years, and not one that could be characterized

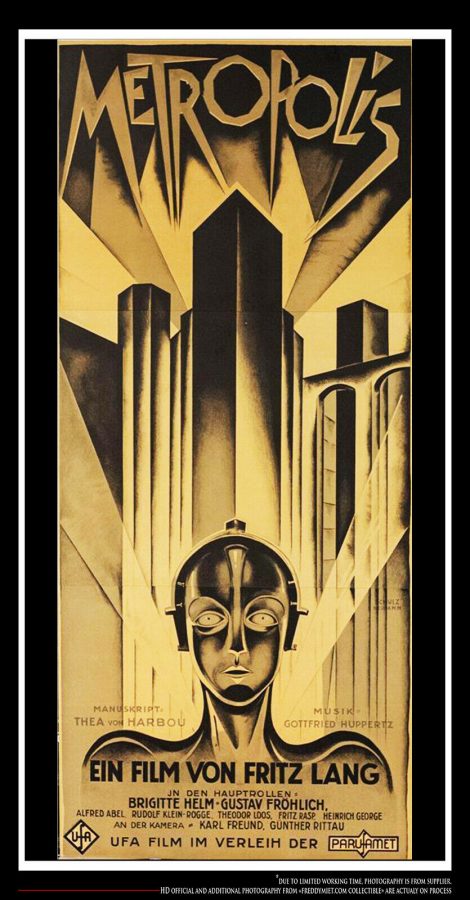

Metropolis

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The stage is set. Three pyramids built up of myriad buildings and angles forge forth unto the screen. Spotlights dance in symmetrical lines, lighting up sections of the structures like a stage. The buildings blur into three black pieces of machinery plunging up and down,