By Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog 1. We are very aware these days of our submersion in the image; that much of our cultural meaning and awareness originates in the consumption of, production of, and of our being represented by images. The burning questions and controversies around the latest development in A.I.-related

Tag: Fraser Hibbitt

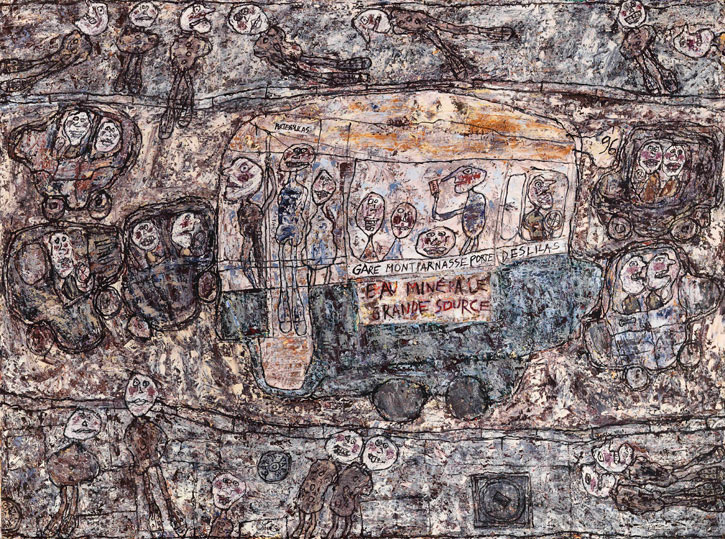

Art Brut, or Outsider Art.

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Sometime in the 1940s, the artist Jean Dubuffet coined the term “Art Brut” which roughly translates as “Raw art”; un-cooked and close to the initial mood of creation; or, the closest representation of the individual’s creative urge before the influence of learning. Much of Modernist art

Thinking About Realism

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Realism tells tales like any other genre, and it is odd that we should be forced through much digression knowing that point. What I mean when I say Realism is the specific genre of fiction that wishes to imitate contemporary life in a ‘realistic’ manner. Realism

Museum of Old and New Art

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Photos from MONA, Carl Kruse and Blooloop In 2006 the Moorilla Museum of Antiquities closed for a huge revamping and after the input of $75 million and five years of construction the Museum of Old and New Art emerged (MONA). Located in Holbart, Tasmania, the museum