Breaking the Waves: Women on Film by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog It is sincerely difficult to write about love. Attempts to do so are often vapid, overly sentimental, gratuitously flowery, or simply boring. We have all written about love; in letters, poetry, texts, emails, journals – we have all thought

Tag: Lars von Trier

A Series On Lars Von Trier, Part 1

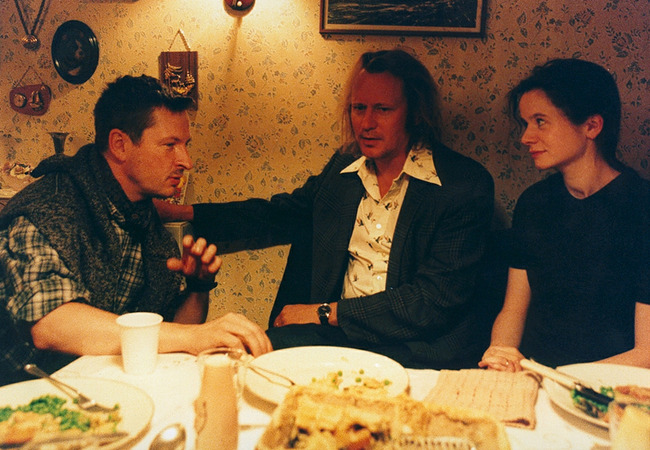

Part 1: A Brief Discussion of Dogme 95 by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog There is a pristineness characterizing the modern film scene. I do not mean a pristineness or cleanliness of character, theme, or narrative, necessarily, but rather of the visual. Films, and other recorded media, have become indescribably high-quality,