by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

It will be inevitable, in this article, to feel a certain sense of unease and difficulty in orienting oneself in front of works that are very different from each other a few years later. You will find all and the opposite of everything. In the past it was easier when faced with a painting, a sculpture, an architecture, to establish the period, to propose a probable dating, because the spirit of the time (what marks an age in itself and determines a taste) resisted longer, it stretched out, without encountering serious obstacles, for decades. Yet the speed of societal and cultural change is reflected in the speed and change in art. The spirit of the times today has certainly not ceased to act; but its range of action no longer differs over decades but over every handful of years, because the changes are more rapid than in the past.

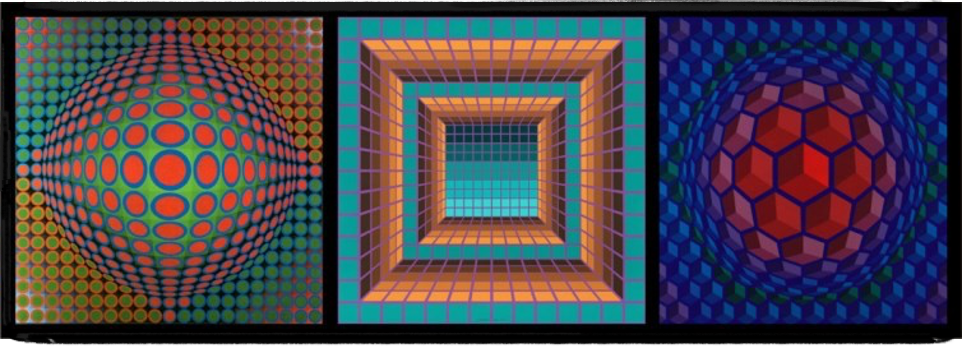

From the end of the fifties the reaction to the informal, to its desecrating and nihilistic fury, passed through different experiences, somehow opposed, such as “Optical Art” and “Pop Art”. Optical art (mostly known with its abbreviated term op art) includes those artistic manifestations interested in the analysis of perceptual and kinetic phenomena. In this context, the artists created, on the one hand, works with their own movement, on the other works that, thanks to a study of perceptual tricks, create different visual effects according to the movements of the viewer, thus soliciting his participation.

Victor Vasarely; Op Art

With these interests, op artists grafted an aversion to any romantic individualism into a line of research connected with the rigorous scientific spirit through groups such as the German Group Zero, the Swiss Kalte Kunst, the French Group de Recherche d’Art Visuel, the Yugoslavian Nove Tendencije.

In the context of op and kinetic art, the production of multiple works designed by the artist but made according to industrial procedures in smaller series of copies, often numbered and signed, began. The artist’s intervention is limited to the design phase: one understands how the multiple is placed side by side and often confused with industrial design, and how it also risks lending itself easily to commercial operations and mystifications.

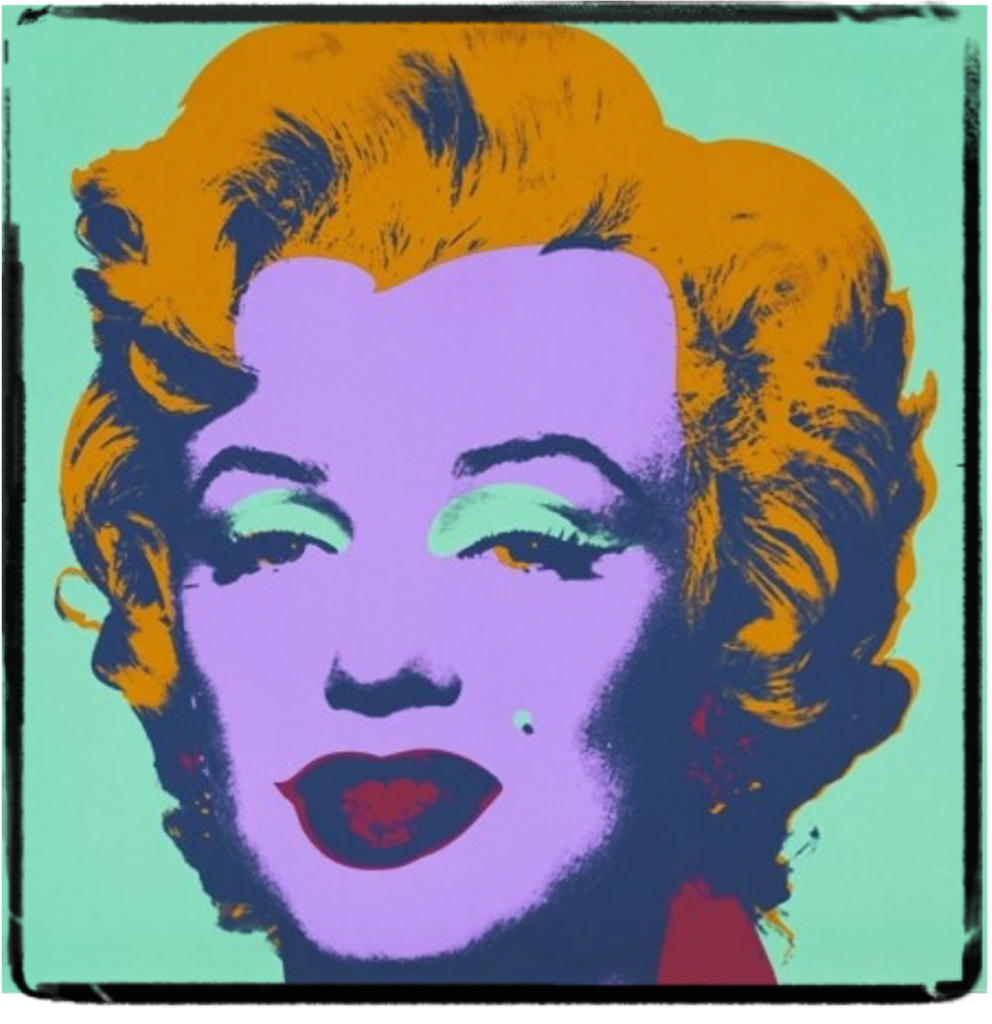

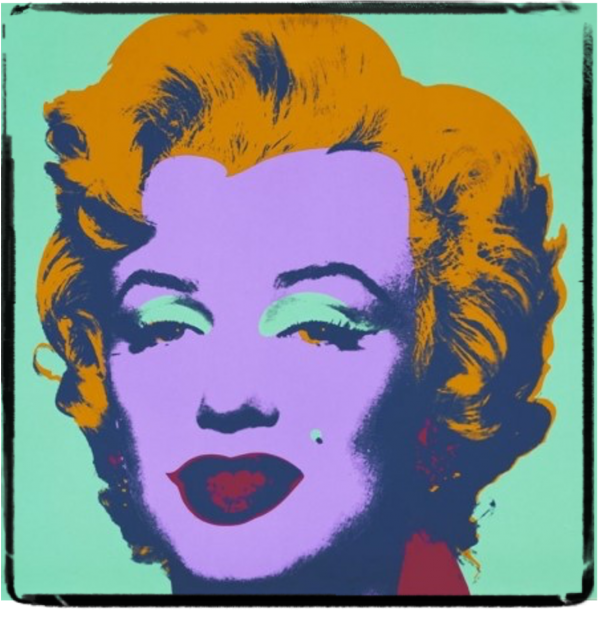

With the so-called pop art (short for popular art) the artist’s interest turned to the world of consumerism, to the Babelic profusion of objects imposed on a daily basis by the system of production and advertising: it’s therefore obvious that this trend would mainly develop in the United States. By isolating the product of daily use, decontextualizing it, transforming it into an idol, a totem, a fetish, pop art alluded to the depersonalization of a world dominated by the profit of things, and ironically celebrated the triumph of goods and launched a cry of alarm.

Artists such as Robert Raushenberg, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein demonstrated their discomfort by reproducing the most usual objects or images favored by the mass media, sometimes with meticulous, hyper-realistic technique, or by remaking them in natural or hyperbolic dimensions, or by using the objects themselves. In 1964 the pop artists were presented, with great success, in the U.S. pavilion of the Venice Biennale: it was the decisive push for the start of a short but intense pop season throughout Europe.

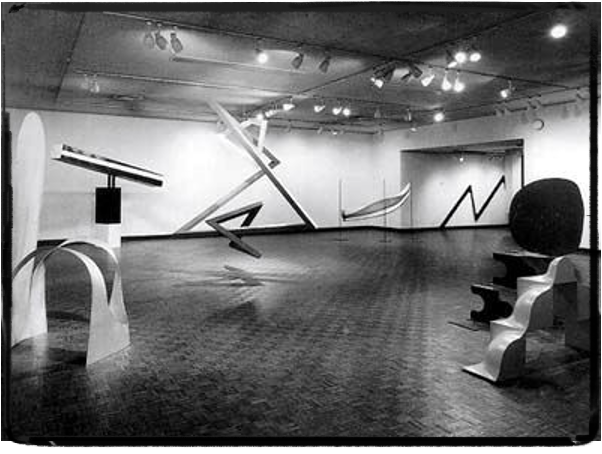

The second half of the sixties, in the whirlwind succession of fashions, saw the affirmation of minimal art (sometimes labeled “Primary Structures”, from the title of a 1966 New York exhibition), not without ties to pop art. The term “minimal” refers to the fact that artists of this trend minimize the complications of form, and aspire to elementary forms using simple and non-traditional materials (concrete, iron, steel, wood, aluminum, plexiglas, etc). This is how often large-scale works of geometric evidence are born,consisting of isolated or repeated modules, with the intention of involving the surrounding space in some way.

Primary Structures, exhibition 1966, New York

The artists of minimal art, pugnacious opponents of the com-modifiable object and in search of elementary volumes (almost in an attempt to trace the origin of forms) were already close to conceptualism, a trend (the term was used for the first time by Sol LeWitt in 1967) which, having abandoned any intention of representation, will make reflection on art prevail and will underline the phase of planning over actual realization. But conceptualism is a phenomenon with rather vague outlines and it is really difficult to frame, given that from time to time poor art, land art,visual poetry, those forms of spectacularization of art represented by happenings and performances. Poor art, however, well underlines the predominant trend in the late sixties, namely the rejection of the traditional artistic object.

Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings”, 1960, New York

One of the reasons that underlie many experiences of recent years has been the anxiety of renewal at all costs (we could also define it as a revival of the spirit of the avantgarde), the rejection of everything that even remotely resembles “already done”. This novelty race combined with a spirit of revolt, distraction, profanation in the sixties and seventies. The artists have reached insurmountable limits: they have applied the label of artistry to practically everything, they have exhibited themselves in the halls of museums, they have even really hurt themselves. The protest against the traditional system of arts has been radical, and often a reaction to the commodification of works; however, we must warn that the market has been able to seize seemingly elusive experiences, by putting into circulation, for example, photographs or recordings of performances, body art events, land art and so on.

Of course, many experiences imbued with such a strong radical spirit have had the merit of demythologizing the aura that surrounded the work of art, but at the same time, a large part of the public has pulled back, unable to understand or even in horror.

In the artistic events after 1945, it must be said, the tools of expression have multiplied, from cinema to video-tapes to electronic instruments and now NFTs, resulting from the most advanced technology, and the artist has seen an increase in her possibilities of manipulation and intervention, able to fully realize demiurgic wishes. Numerous operators were active with very different means: the case of Andy Warhol teaches, with his decisive contribution to the development of underground cinema.

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, 1967; New York, collection of Leo Castelli

Andy Warhol’s position is highly critical of mass media-induced distortion. The artist works on sensational images, the faces made famous by the news (Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy), the photographs of a disastrous fire, of a spectacular car accident. The media repeatedly propose the same images to us, manipulate them, deform them, and Warhol thus renders them, almost unrecognizable, insisted on some detail, half-erased for the rest. They are the same fragments of reality that are offered to us every day by newspapers, television, cinema, but which no longer have the power to strike us, they leave us indifferent (and very soon reality itself does not arouse different reactions in us).

============

The blog home page is at https://carlkruse.net

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Asia Leonardi include those on Frida Kahlo, Charlotte Salomon, More on Action Painting, and Jackson Pollock.

Love pop and optical art and happy to see you cover it here.

Thanks for stopping by Estela.

Carl Kruse

Never understood minimal art. Yes of course the concept and what the artist is trying to achieve. But it falls flat for me.

Minimal Art in spite of its often simplicity is an extreme approach to Art, not just abstract, but often taking abstraction to basic geometric form, its own reality. It is for me conceptual Art though I suspect many Minimalists would not call it that. I understand how it could fall flat for you.

Carl Kruse