by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

The fundamental reality of creation is solitude. This is what Lecoq tells us, and, when I turned around and faced the audience, clothed with my red nose for the first time, I did indeed feel very alone.

We had started doing clown the week before, but we only have one session a week with our Lecoq tutor, Ally Cologna, who had trained with Lecoq before his death in 1999. Clowning, as interpreted by French theater practitioner Jacques Lecoq, involves the smallest mask available to the actor: the little red nose, and normally comes last in a series of other more obscuring masks, including larval and expressive masks. Due to its smallness and thus its tendency to expose the actor beneath it, the red nose is often seen as the most challenging mask of all.

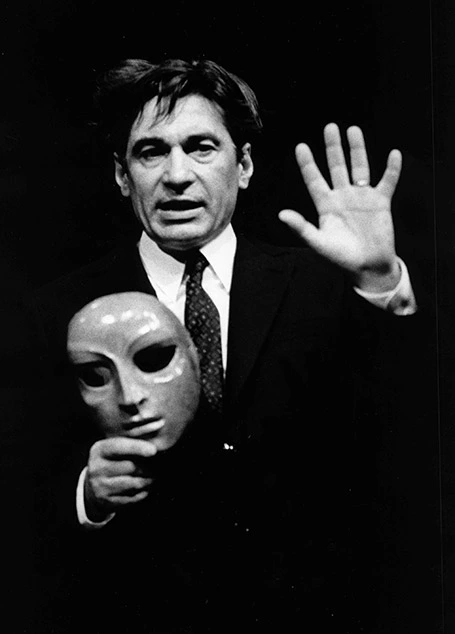

Jacques Lecoq

The week prior to my own attempt at clown, Ally had told us that we were to go up one at a time and complete a few basic tasks. The first was to walk around the space, without the red nose on, during which time a member of the audience would come up to the space and mimic our walk as best they could. Once a rhythm had been negotiated between actor and mimicker, the actor would turn round and watch their comrade’s impression of the walk. Then, when the time was right, the actor would go behind the mimicker and mimic their impression of their own walk. After this, the mimicker would leave the space and the actor was to continue walking in the particular fashion that had been observed by the mimicker in order to receive and experience the sensation of interpreting another’s perspective of their personal movement patterns.

Eventually, the actor would be instructed by Ally to walk as ‘themselves’ once more. For the actor in the space, discovering the unexpected picture which had been painted of them by the mimicker was often a cause for hilarity and a great method to release tension; for myself, the mere presence of a fellow actor in the space prior to entering into this new phase of our acting journey – clown – reassured me quite. Lecoq calls this practice ‘ways of walking’ and states that it can help the student to find their own characteristic walk which is a natural development from their own personal way of walking, not a forced comic walk which is artificially built from nothing. Lecoq also works with ‘forbidden gestures’, those which are not normally permitted for adults and which we quell and crush deep within our childhood so as to be more societally respected and, perhaps, ‘normal’, if there were such a thing. Lecoq suggests that the psychologically freeing nature of this work, whereby the actor will hopefully find himself much more open, less defensive, and more receptive, will allow the actor to find his ‘primary clown’, which, as Nathalie Ellis-Einhorn describes it, might be an access to ‘childish joy, curiosity and vulnerability to the world, [with the knowledge that] children are also spiteful’ (from her thesis: I.M. L.O.S.T! a show about clowns). The clown might be innocent and unguarded in his presence, but this does not mean that he is always kind or sympathetic to both his Monsieur Loyal or the other clowns which might join him in the space. This statement should not be interpreted insidiously, as, according to Lecoq, ‘the clown needs no conflict because he is in a permanent state of conflict, notably with himself’. Rather than making the clown inauthentically selfish or impudent, this inner conflict results from a desperate need for attention and love which might materialize in the clown blaming others for his ‘flops’ in order to gain praise for his own behavior, but this is not inherently egocentric or insolent conduct that comes from a protective societal mask.

After the walking exercise, Ally would instruct the actor in the space to turn around and put their red nose on. Ally was clear that neither the red nose nor the act of clowning must be referred to in the duration of the actor’s clowning practice, or else the illusion of the clown be broken. I suppose this makes sense; we do not usually refer to the characters we embody on stage, lest the Fourth Wall be irreparably shattered. It might make even MORE sense with a clown; as a clown is itself ‘the person underneath, stripped bare for us all to see’ (Lecoq, The Moving Body, p. 143), it makes sense that the person should not refer to their clown in case they become even insensitive to this vulnerable, exposed part of themselves, which might have been previously unseen by their colleagues. I don’t know. I’m merely hypothesizing.

My colleagues and I saw a few different clowns on the first day of our clown training. It is wonderful to watch someone grapple with the candidness and the verity that the red nose offers them, but this is a task that is sometimes too much for the actor to handle, at least on the first try. In fact, rather a large proportion of those first clowns ‘telephoned’, either a little or, God forbid, a hell of a lot. ‘Telephoning’ in clown occurs when the clown deliberately leads himself down a path of reactions and actions rather than being ‘entirely without defense…[and] always [] in a state of reaction and surprise’ as Lecoq encourages. If the clowns begins preceding his own intentions, one might say that the actor clowning had begun to play a role, or put on a coat, as opposed to being innocent and open to the possibilities of the moment. I ‘telephoned’ a few times during my own turn at clown, I think. But I’ll get on to that.

Students at the L’ecole Internationale de Theatre de Jacque Lecoq find their clown.

I want to comment for a moment on the character that our teacher Ally evolved into when she was provoking our clowns. She called it ‘Madame Provocateur’ after ‘Monsieur Loyal’ of circus and clowning tradition, otherwise known as the ringmaster or ringleader. During many difficult moments for my colleagues’ first clownings, ‘Madame Provocateur’ was capable of eliciting brilliantly authentic and, often, hilarious responses and actions out of the unseasoned young clowns before her. She was oftentimes brash, offensive, and extreme in her berating of the clowns, but one never felt unsafe or at all nervous in her presence due to the fact that Ally herself was unable to keep a completely straight face as she scolded the pitiful clowns on stage. Ally is a phenomenal teacher, and I shall surely miss her when the time comes for me to finish my training at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama.

I went up to clown during our second lesson of clowning with Ally. My walk, as displayed lovingly by my colleague, was rather more ‘sexy’ than I had previously believed. I was rather sure that I had more of a swagger, but I took on the exaggerated version of my walk produced by my colleague and strolled around with it for a while before shaking it off and going to put on my nose. I had thought fleetingly about what my clown might be and had concluded that it was likely going to be quite a grotesque or obnoxious clown, perhaps speaking back to Madame Provocateur or being generally unpleasant and profane (from a most unguarded state, of course). But what I discovered that day was sadness, and loneliness, and an inability to understand why my audience was laughing at me. I say this not to overemphasise the freedom that I found in my clown, for my clown was not entirely candid; as I said, I’m certain that I did ‘telephone’ a few times, for it is oddly difficult not to react defensively to some of the comments thrown towards one by Madame Provocateur. However, the sympathy with which my clown was received by the audience made me feel so very safe, safe enough that I was not afraid to feel sad and misunderstood and equally unafraid to display my desperation to be loved. How much I wanted to be loved and seen by my colleagues. How I wanted them to watch me and smile with me and love me. I suppose this clown is much like some personas which I indulge in in my personal life. My twin sister and I still continue the role-playing which we started when we were much younger, which involves myself as the younger, dumber, and more endearing character and my sister as the character of authority and tyranny. All the bravado and crudeness of my habitual social mask were stripped away by my clown, and all that was left was a timid, pitiful little clown who thought little of themselves. I wonder how I did not see this coming. My colleagues commented that they had not expected such a clown from me either and that they believed that they had now seen a side of me which they had only spotted in glimpses prior to then.

I am excited to see where I can go with my clown, but I sometimes fear that I will begin to orchestrate my clown’s reactions and tendencies should I get too comfortable with how my first clown was received by my audience. The novelty of my first clown lent itself well to honesty and openness, but even in my second attempt at clowning I found myself ‘telephoning’ a little more than I had the first time. In my third attempt, I found it difficult to put words into my clown’s feelings, and ended up being rather too silent and ‘meek’ compared to the other clowns, who readily answered Madame Provocateur’s provocations.

Despite my uncertainty about how this side of myself came to be that which lent itself to my clown, I believe that I know this ‘clown’ very well. It is that part of my being which believes that I am quite useless, however hard I try, and it indeed does try hard! Perhaps clowning is the safest place wherein I can explore this darkness and melancholy, for the clown mask enables one to experience a conflict of self in a way that does not linger on into the rest of one’s day, or week, or month. Lecoq speaks of the difficulty that might arise when exploring these intimate depths of emotion:

‘The student must be prevented from becoming too caught up in playing their clown, since it is the dramatic territory which brings them into closest contact with their own selves.’

And, importantly, that:

‘[T]he clown should never be hurtful for the actor.’

I wish that I could comfort my clown and tell it that it is worthy of the love it desires so intensely from its audience. But equally, I wish to exploit and indulge in the emotions that the clown allows me to experience while eliciting laughter and pitiful sighs and groans from the audience, because these small indications of validation might help me to understand that I, and this particular aspect of my being, are fundamentally ridiculous, and that this part of me is merely an essential part of what it is to be human.

(All quotations described as coming from Jacques Lecoq are from the book ‘The Moving Body: Teaching Creative Theatre’, trans. David Bradby, Methuen, 2000, of which the original text, ‘Le Corps Poétique’, was published in 1997 by Actes Sud-Papiers.)

==============

The Carl Kruse Arts Blog Homepage.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles on acting and theater training by Hazel include Six Viewpoints and Channeling Animals.

The blog’s last post was on the Justified + Ancient exhibit near Sarasota, Florida.

You can also find Carl Kruse on Stage32.

Enjoyed Hazel’s experience on finding her clown.