by Carl Kruse Carl Kruse Arts invites its readers to an exclusive preview of the art exhibit Face Off at the Vorona Galerie, Friedbergstraße 12, 14057 Berlin on Thursday, February 19, 2026 starting at 6pm. This is a private tour by gallery owner Julia Vorozhtsova and art curator Jenia Yanes on the day before the

Category: Arts

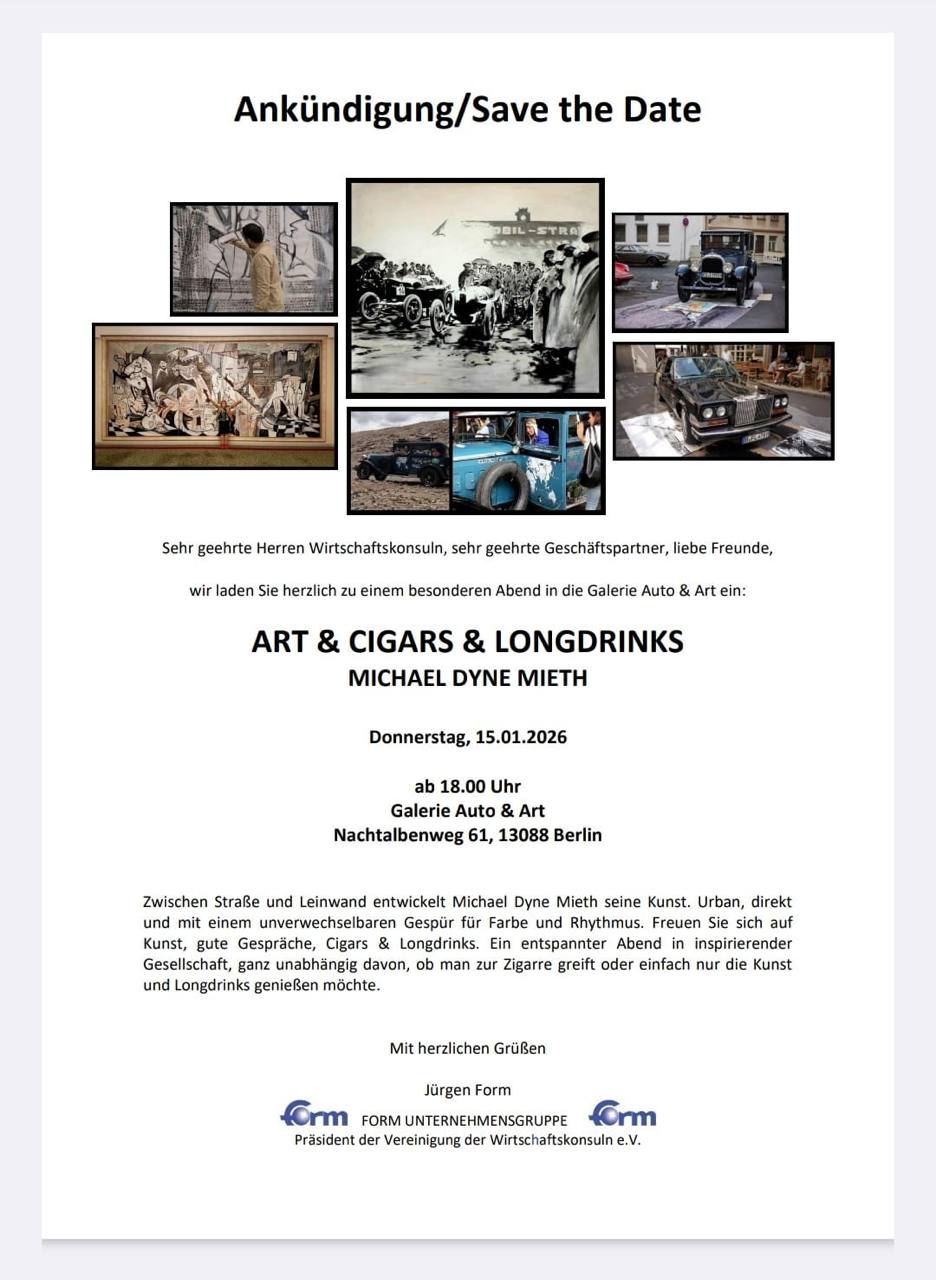

A Night of Art, Cigars and Long Drinks in Berlin

by Carl Kruse Carl Kruse Arts cordially invites you to a special evening at the Auto & Art Gallery called ART | CIGARS & LONG DRINKS to take place Thursday, January 15, 2026 from 6:00 PM at the Auto & Art Gallery, Nachtalbenweg 61, 13088 Berlin. The event will feature an art exhibit from artist

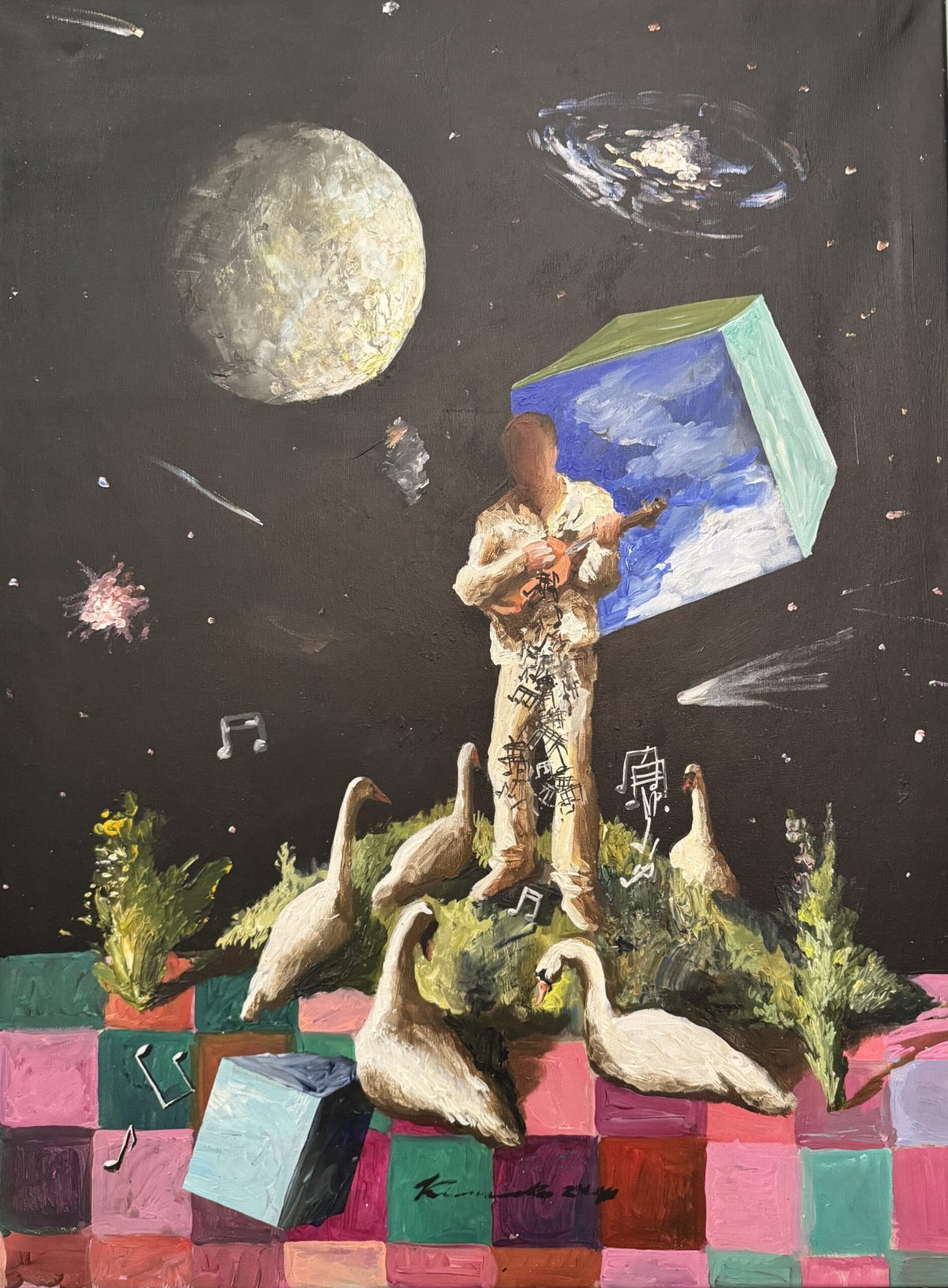

A Conversation with Artist Yury Kharchenko in Berlin

by Carl Kruse The Carl Arts Blog invites all to a conversation with artist Yury Kharchenko to take place this Monday, October 6 at 7pm at the TAZ Canteen located on Friedrichstr. 21 in Berlin. Admission is free and the event-space is barrier free. Carl Kruse Arts has often focused on Yury’s work these past

Another Art Brunch and Tour With Artist Helena Kauppila

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog (Ars Lumens) would like to invite all to the third Art Brunch at the studio of Helena Kauppila, on Sunday, October 5, 2025, starting at 11:45 am on the fourth floor of Ackerstrasse 81, 13355 Berlin. There will be a welcome drink, some finger foods, and a

Art Exhibition with Helena Kauppila

by Carl Kruse Friend of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Helena Kauppila invites all to the opening reception of Ein guter Grund, a duo exhibition at Alter Kiosk Berlin. The event takes place on Friday, July 18th, starting at 18:00, and there will be a performance. Opening ReceptionEin guter GrundErnst Handl and Helena KauppilaFriday, July

Artist Helena Kauppila at the Miettinen Collection

by Carl Kruse Our artist friend Helena Kauppila who we have done several events with in the past (see here and here also) invites all followers of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog for her ongoing exhibition at the Miettinen Collection. Here is the invite from Helena: “I am honored that my recent work Early Life

Maria Nitulescu at the Till Richter Museum

by Carl Kruse Our friend Maria Nitulescu invites all to her solo exhibition: “At the Crossroads of Memory” taking place at the Till Richter Museum, Schloss Buggenhagen, Buggenhagen (near Usedom), Germany. The exhibition goes until 31 August 2025. Museum website: https://tillrichtermuseum.org/ Google Maps Location: https://g.co/kgs/NNda6wJ panning two rooms, the exhibition explores the profound connection between

Jade Cassidy Art Exhibit in Berlin

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog in conjunction with the Ivy Circle Berlin is happy to invite all to an art exhibit of artist Jade Cassidy taking place on Wednesday, February 12, 2025 from 6-9 p.m. at the Quantum Gallery on Kurfürstendamm 210 in West Berlin. The event will feature complimentary champagne from

Tour of Boros Art Bunker In Berlin

By Carl Kruse The Cambridge Society invites members of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog to a private tour of the iconoclastic Boros Bunker art collection in Berlin. The event also is co-sponsored by the Ivy Circle in Berlin (of which Carl Kruse is the director). Spread over 3,000 sq m of a converted air-raid bunker,

Art Brunch in Berlin with Artist Helena Kauppila

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog in conjunction with the Ivy Circle Berlin would like to invite all to its second Art Brunch at the studio of Helena Kauppila, on Saturday, October 5, 2024, starting at 11:45 am on the fourth floor of Ackerstrasse 81, 13355 Berlin There will be a welcome and