by Hazel Anna Rogers The sun has been shining for some time now. At first, warmth came from behind bulbous grey clouds, yielding a muggy, wet heat, but now light has taken precedence and grass glows white in its piercing rays. We were walking on one such sunny day and stopped beside the book shop

Category: Hazel Anna Rogers

The Legacy of the Satyr

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The passing-down of literature fascinates me. I find something utterly awe-inducing in the ability of human language to convey a narrative generation after generation, and for us to have the knowledge and ingenuity to understand the importance of preserving great stories and characters. I suppose

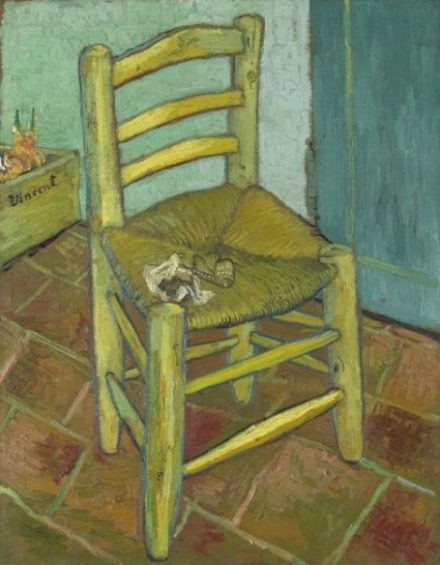

Van Gogh’s Chair: Omens of Tragedy

By Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog I first saw Vincent Van Gogh’s painting ‘Van Gogh’s Chair’ (1888) in secondary school, in the middle of an art class. My art teacher had no particular regard for art history. She found it uninteresting, and it was never a fundamental part of the classes

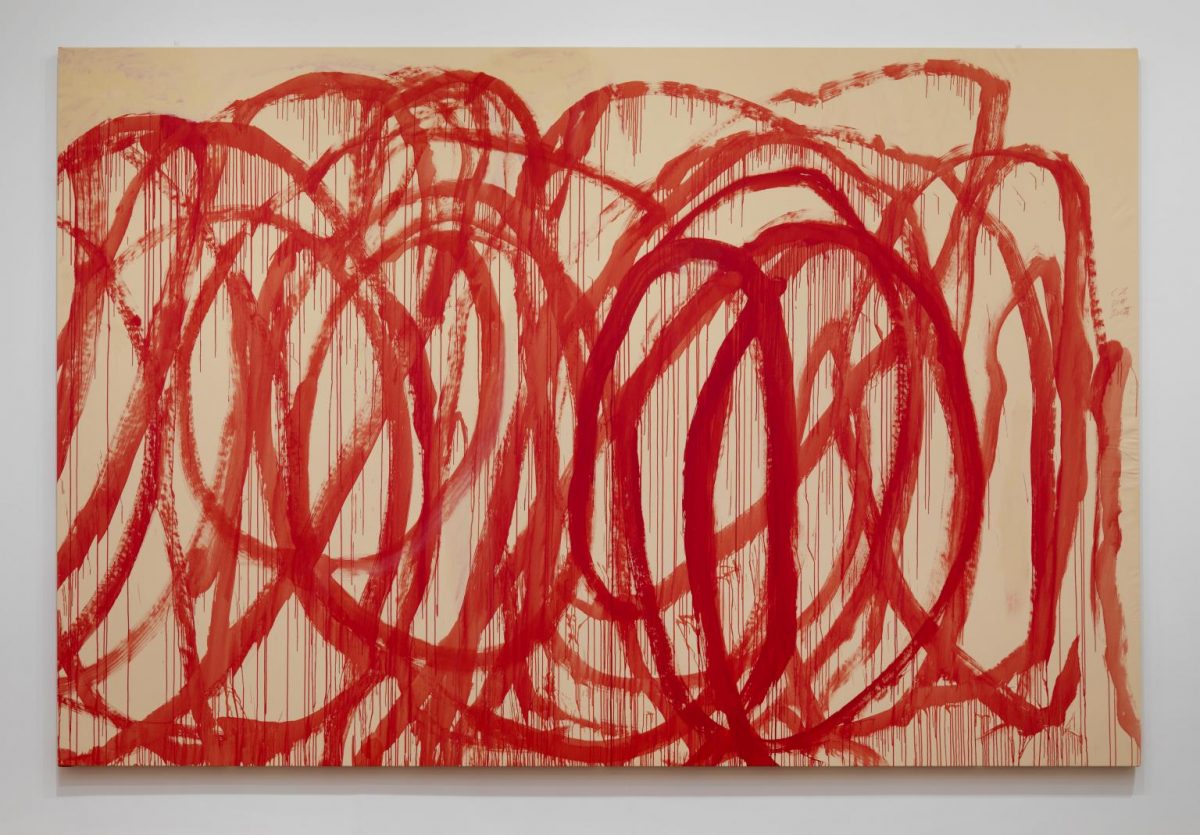

When did we Stop Criticizing Art?

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog When I was around 13, I visited the Tate Gallery at the Liverpool Docks in Northern England primarily to see an exhibition of J.M.W. Turner and Cy Twombly, a starkly contrasting set of artists and the latter of which I actually had next-to-no prior knowledge