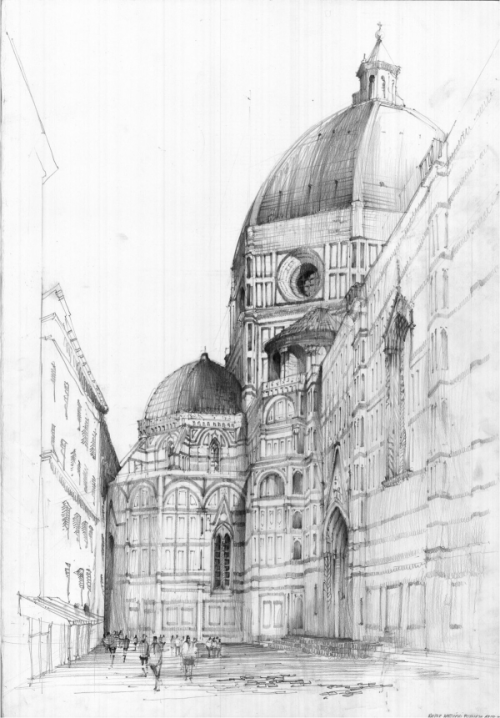

By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), architect and engineer, sculptor and painter, is universally considered the pioneer of the Italian Renaissance and the creator of an approach to architecture that would dominate the European art scene, at least until the end of the 19th century. Through a passionate study

Category: Italy

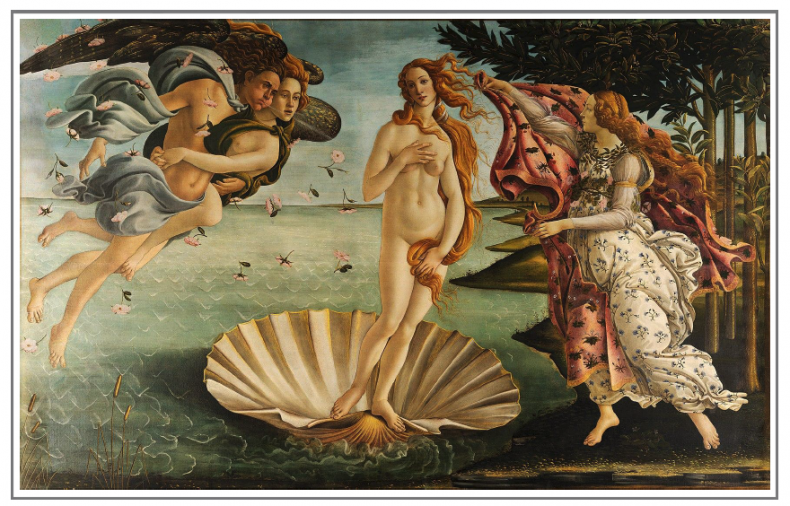

Simonetta Vespucci: Venus of the Renaissance

By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog In the church of Florence of San Salvatore Ognissanti, where the secular exponents of her family are exhibited, rests today the beautiful Simonetta Vespucci in her secular sleep. But there was a time when the prodigious beauty was the inspiring muse of major Renaissance artists, such

Andrea Liguori, a Wonderful Mind in Berlin

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Into the urban traffic of Berlin so many people are walking, with them come ideas from all over the world, sometimes changing the surrounding environment. This is the case of Andrea Liguori, an architect from Palermo who has now lived in Berlin for many years. I