by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The passing-down of literature fascinates me. I find something utterly awe-inducing in the ability of human language to convey a narrative generation after generation, and for us to have the knowledge and ingenuity to understand the importance of preserving great stories and characters. I suppose

Tag: Art

Andrea Liguori, a Wonderful Mind in Berlin

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Into the urban traffic of Berlin so many people are walking, with them come ideas from all over the world, sometimes changing the surrounding environment. This is the case of Andrea Liguori, an architect from Palermo who has now lived in Berlin for many years. I

When did we Stop Criticizing Art?

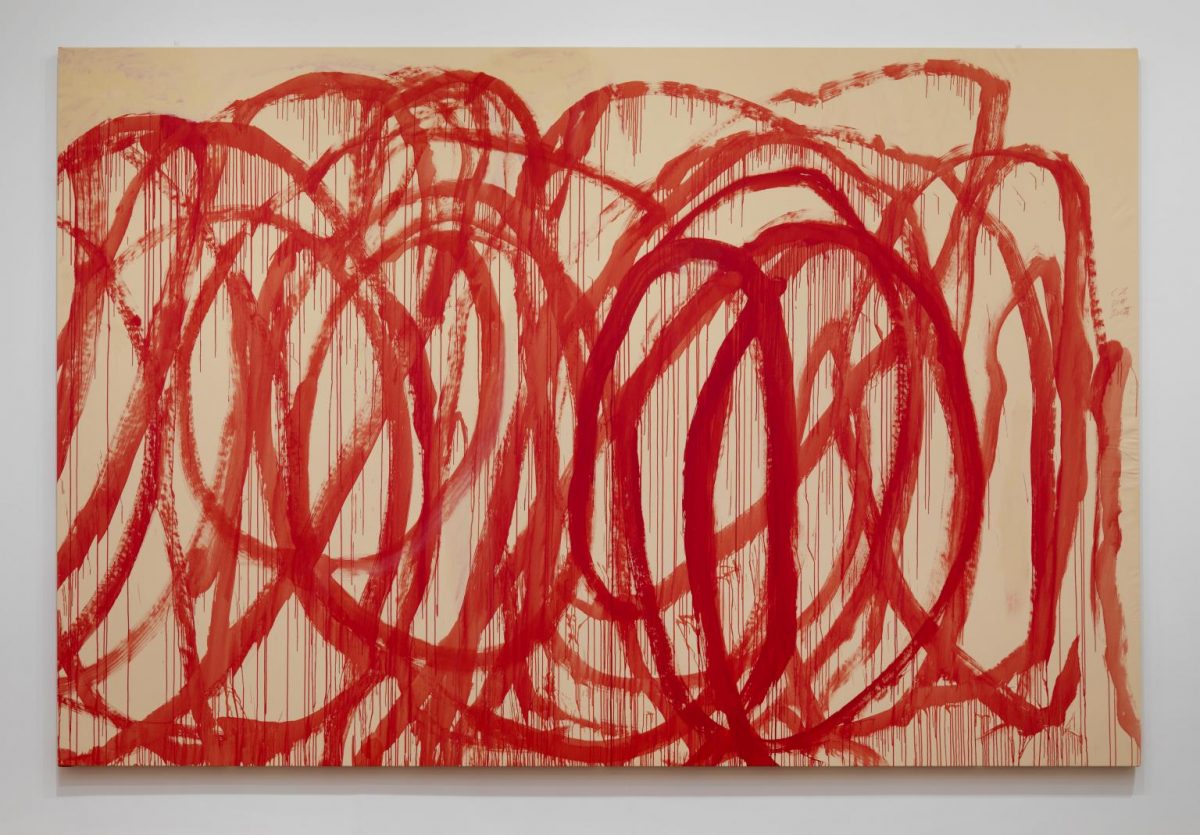

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog When I was around 13, I visited the Tate Gallery at the Liverpool Docks in Northern England primarily to see an exhibition of J.M.W. Turner and Cy Twombly, a starkly contrasting set of artists and the latter of which I actually had next-to-no prior knowledge