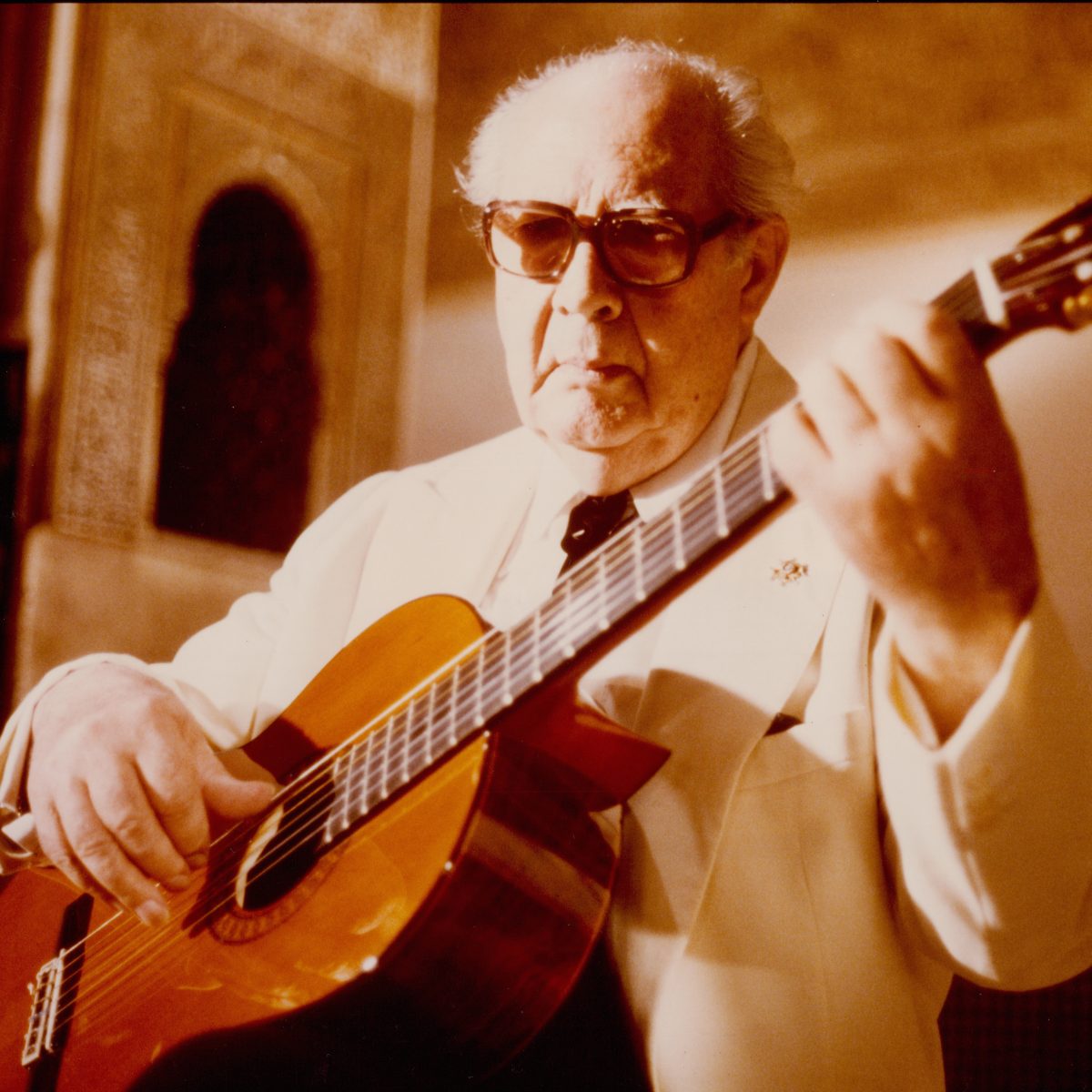

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The seventy-four-year-old maestro sits plump in a large wicker chair. His gut ovals as he looks out from his balcony towards the Mediterranean Sea. His home is large upon the hill, overlooking an olive grove which blinks out the Andalusian heat. Close by is Granada, the

Tag: Carl Kruse Blog

Bowie’s Alter Ego That Transcends Death: Major Tom

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog It is 1969, and the young David Jones, better known as David Bowie, begins to ascend the world stage thanks to the launch of his latest single, Space Oddity. Likely influenced by the space race, the tales of Ray Bradbury, and undoubtedly by 2001: A Space Odyssey. The single

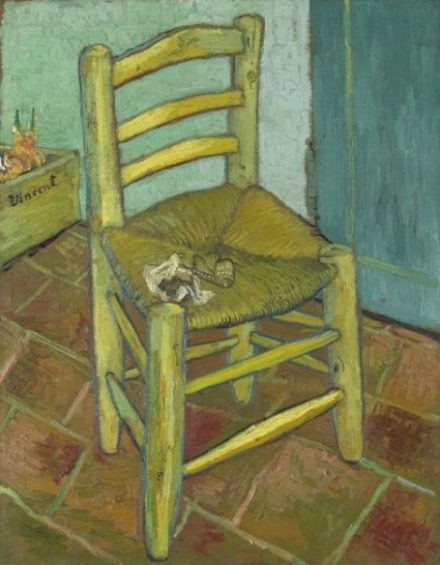

Van Gogh’s Chair: Omens of Tragedy

By Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog I first saw Vincent Van Gogh’s painting ‘Van Gogh’s Chair’ (1888) in secondary school, in the middle of an art class. My art teacher had no particular regard for art history. She found it uninteresting, and it was never a fundamental part of the classes

Yury Kharchenko – Upcoming Hamburg and Berlin Exhibits

by Carl Kruse It has been a busy season for my artist friend Yury Kharchenko with the completion of several new works, the latest being a series that is generating controversy though the artworks have yet to be publicly exhibited. In these latest works, Kharchenko depicts comic and pop culture icons at the entrance to

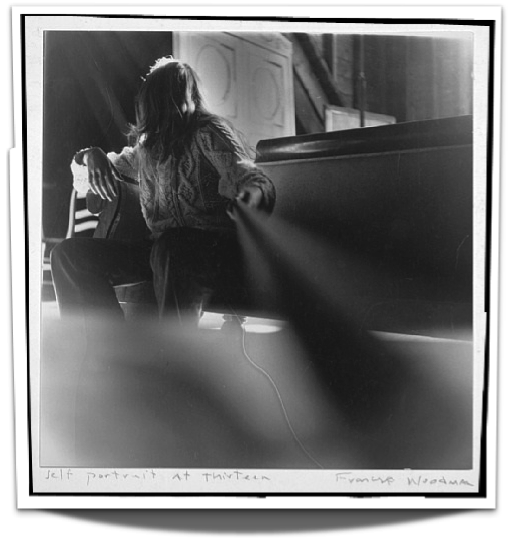

Between Introspection and Surrealism: the Photography of Francesca Woodman

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog One day in 1977, a young girl entered the “Maldoror” art gallery in Rome, handed the owner a gray box and exclaimed: “I’m a photographer!” She is not yet twenty and her name is Francesca Woodman. Born in Denver in April 1958, Francesca was the daughter