by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

When I was around 13, I visited the Tate Gallery at the Liverpool Docks in Northern England primarily to see an exhibition of J.M.W. Turner and Cy Twombly, a starkly contrasting set of artists and the latter of which I actually had next-to-no prior knowledge of. Turner’s tableaux were mesmerizing, a sheer cacophony of violent maritime depictions in furious reds and oranges juxtaposed to ominous grey skylines. The walls of the gallery were filled with gloriously calm sunsets at sea alongside terrifying raging flames and waves that curved and swayed and spat like sharks feasting on shoals of fish. It was wonderful, an utterly overwhelming delight for the senses.

“Fishermen At Sea,” J.M.W. Turner (1796) – Image courtesy Tate Gallery

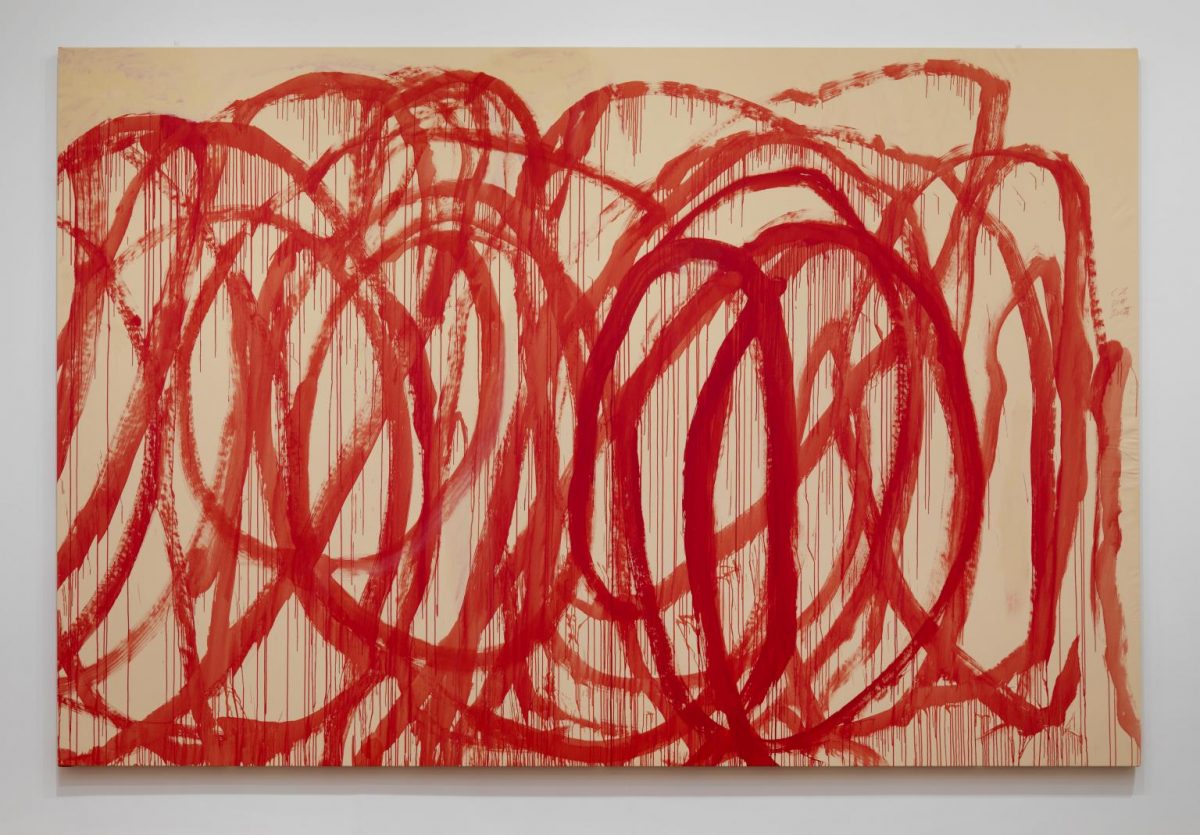

In the next room on I was suddenly surrounded by Cy Twombly’s enormous canvases. Scrawls of paint had been twirled and splatted and daubed onto the huge white expanses creating a graffiti-like effect, some with the appearance of words. I hated it. It felt all wrong, an expression of seeming carelessness towards the production of his masterpieces. After having wandered dreamily through Turner’s paintings, this felt like a punch in the eyes, a pointlessly unartistic exposition in the name of ‘art’. Yet, I felt unable to say anything against those huge, grotesque paintings, being observed as they were by a silent audience of respectful spectators.

“Untitled (Bacchus),” Cy Twombly (2008) – Image courtesy of Tate Gallery

I understand the differences in artistry and approach to creation much more now than I did at 13. I understand that the process of creating a masterpiece is not prescriptive, nor is it defined by one particular artistic style. I also understand that the emotions I felt, being surrounded by Twombly’s scribbles, were valid sentiments, and likely would have pleased Twombly himself should I have recounted them to him. But that doesn’t discount my anger, my frustration that art with no merit except its colossal size and thus imposing presence should be beside the tender daubs of someone like Turner. The art world has always had opposing views on what is, or is not, art, but that’s not what I’m talking about here. I don’t disagree that Twombly’s paintings are art. I also don’t wish to debate what ‘beauty’ is with regards to art, as it isn’t always relevant. A piece of art can be incredible without being beautiful. I just want to understand how it is we came to the art world of today, of the 21st Century, where we no longer criticise art.

I am in a generation bewitched by social media, a generation that is unashamedly narcissistic and that relishes self-importance. It is also the generation that produced the Instagram poet Rupi Kaur, along with her pages of simplistic, immature poetry. I have been to slam poetry contests where the winner was crowned not for poetic merit, but for loudly proclaiming how much hardship they had endured through their life. If I sound embittered, it’s because I am. Bygone eras are much the talk of mine and past generations, times when music was exciting, when people wrote letters, when people read books and wrote ones just as wonderful. I often think about the jazz scene of 1920’s Harlem, a sea of exciting talent emerging from an ever-increasing black population, with such greats as Fats Waller and Willie The Lion Smith striking piano keys in the jazz clubs that popped up left right and centre as New York became the epicentre of jazz in the 1930s. It’s that feeling of ‘You had to be there’. I have no doubt in my mind that the musicians playing in Harlem in the 1920s were often showered with tomatoes, booed off-stage, and not invited back until they were better in their respective trades. To be criticised is to be encouraged, to have the drive to get better, to show how good you can really be if you put your mind to something.

Part of the problem with new art is its audience. We can no longer heckle bad poets and bad musicians, or tell people that their paintings are unimaginative or uninspiring. We live, strangely, in a social climate that tells us we need ‘trigger warnings’ for certain books we read, while we watch poets read lines that shout about how they were bullied, raped, oppressed, and harassed without a metaphor in sight to disguise their meanings. And we sit, stony-faced, silent, and clap them, congratulate them on how brave they are to tell us all how much we should pity them. Art is no longer questioned, at least not within the younger generations that I am often amongst.

I remember when I was 15 and won the Young Poet Laureateship for the region where I grew up. Time and time again I would write poems, and time and time again my family would tell me they needed improving, or that they weren’t good at all. Criticism was a wonderful thing for me. It allowed me to grow as an artist, to shape my language into something subtle, sharp and resonant. I was better for it, a more rounded poet and writer, and never once did I resent feedback on my writing, be it bad, or worse, dismissive.

In a world obsessed with art but unable to distinguish the good from the purely egotistical, we find ourselves stranded. I still fell as though I am in that gallery, looking at Twombly’s artwork, perplexed and unimpressed. We discussed the paintings when we went back to school. Twombly’s paintings were ‘experimental’, ‘disturbing’, ‘interesting’, and ‘thought-provoking’. The space to say how much I hated them disappeared quickly as an overriding sentiment of respect for Twombly’s art overtook the classroom. Was it because it was in a gallery, thus it had to be worthy of our awe and wonder? I can’t say. But I think back on that day where I remained silent, and I also think about what would have happened if my family had praised my poetry when they in fact thought it flawed, meaningless and dull. And I will toast to the day that I have the courage to stand up and tell a bad poet what I really think of them, when I have the courage to tell my friend that her indie alternative jazz band needs to get their act together, because all of their music sounds the damn same. I will praise the day that someone tells me they didn’t like my poetry performance, that it was crass or forced or unintelligent, and I will relish the possibility of self-improvement under the motivation of their harsh words. In a world that censors negativity in the face of art, I hope that we can learn to speak our minds once again.

===================

Carl Kruse – Ars Lumen Home Page – Here

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Last blog post was on Escher

Another post by Hazel Anna Rogers – Music, Memory, the Cloud

Carl Kruse is also on Pinterest.

Wait. Did we ever stop criticizing art?

Not at all, but may have we gotten more permissive what art is?