by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

[… ] with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls,

[… ] who drove cross-country seventy-two hours to find out if I had a vision or you had a vision or he had a vision to find out Eternity [… ] who dreamt and made incarnate gaps in Time & Space through images juxtaposed, and trapped the archangel of the soul between 2 visual images and joined the elemental verbs and set the noun and dash of consciousness together jumping with sensation of Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus, to recreate the syntax and measure of poor human prose…”

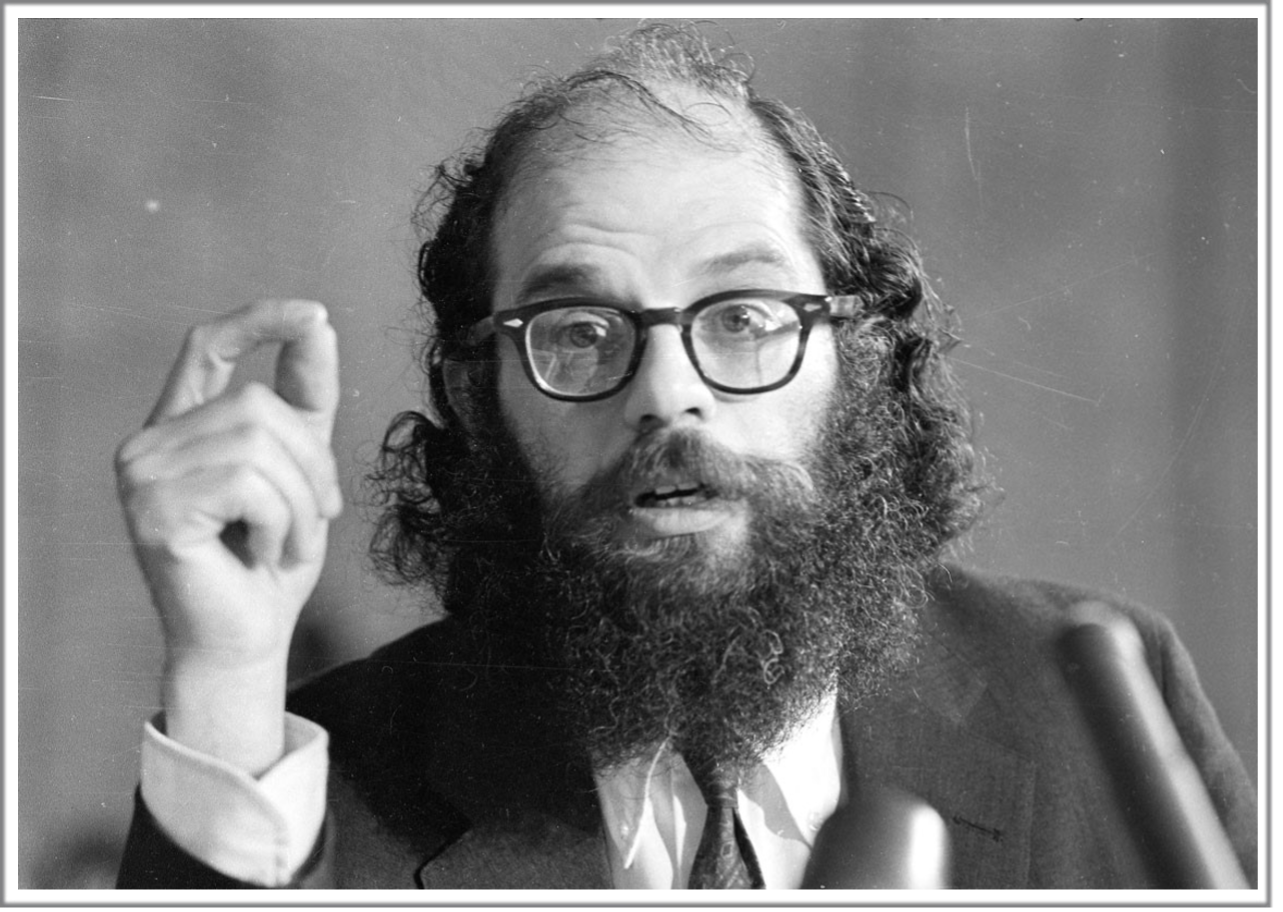

Howl, by Allen Ginsberg, San Francisco 1955-56

The Beats concentrated particularly in San Francisco. The Californian revival had already begun after the Second World War, with the arrival of thousands of European refugees, and was shaping the beautiful city on its footprints, characterizing it as the American city less linked to local traditions.

In the unsettling wave of mass conformism accompanied by the economic boom beginning in the late 1940s, San Francisco opposed itself as an oasis of individualism, perhaps thanks to the Mediterranean and Mexican footprints, which had painted it with those characteristic features of the “laissez-faire,” of the “dolce far niente,” a peculiarity that would hardly be found in other American cities of the period. San Francisco thus built a reputation of the “easiest city in America, and was soon populated by avant-garde artists, old Dadaist anarchists, rebellious boys who had left their homes. In this context, was born, and strengthened the “Beat Generation,” an expression of the critic John Clellon Holmes, which was to indicate what we remember today as “burnt youth.” They were not illustrious writers supported by large publishing houses, but troubled boys who rejected the moral and social systems of bourgeois society, in search of discovery -of a full self, of real-life, of new methods to approach life. It almost seems from the moment Holmes called them Beat Generation, these guys started drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana, writing poetry, hitchhiking around America.

Of course, this is not the first youth anti-bourgeois movement and perhaps Baudelaire’s drunkenness was not so different from Hemingway’s, even though their literary programs were certainly so. Both anti-bourgeois, they led a violent battle to overcome the conformism of the time and impose their aesthetic creed even before the moral one.

Bourgeois conformism flattens the personality, levels the souls, implicitly establishes the moral and social structures of the mass community, which becomes increasingly impersonal, anonymous, and flat. The boys feel suffocated, silenced in a “misunderstood” silence. Hence the need for expression, living experiences, through which to seek an autonomous reality, free from conventional norms. Their experiences tend to take over the extremes of personality, perhaps because in this very one they hope to find the moral key that will serve as a solution to the eternal problem of good and evil.

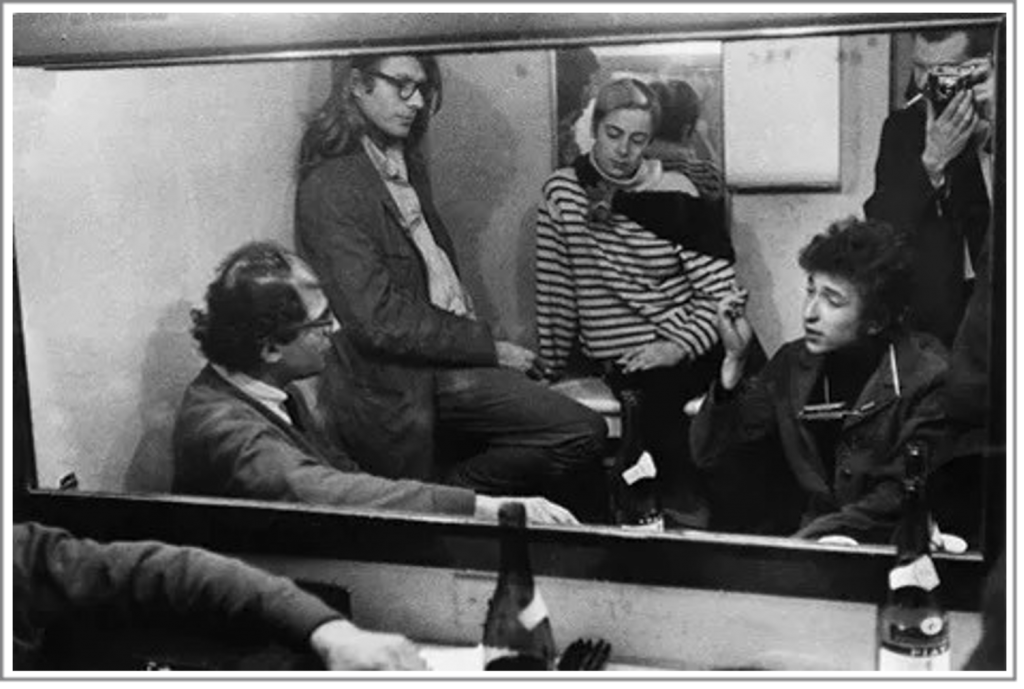

Daniel Kramer backstage at McCarter Theater, in Princeton, New Jersey, September, 1964.

To the Beat Generation belong, writers and poets, whose texts were negatively received by bourgeois and conformist critics, who, in the particular case of Allen Ginsberg, was described as “totally negative and unnecessarily obscene.” The violence with which the art of the Beat Generation has been welcomed is the same violence of the mass society that has led them to separate themselves from it.

The character of the American Beat Generation and their literary productions consists in their poetic proposals and experiences of a spiritual nature. Their way of acting was a reflection of the adolescent anxieties cultivated in bourgeois worldliness. The typical characters in Jack Kerouac’s books perform gestures whose families would pay handsomely for not seeing their children perform –watching them get drunk on alcohol and drugs, live as vagrants, piercing the sole of their shoes as they step on the accelerator, venting their energy, their anxiety for life, in an intensity that if taken out of context would seem unjustified. “We have to go and we don‘t have to stop until we get there.” “Where are we going?” “I don‘t know, but we have to go.“

To see it this way, it would seem that their need is to escape, but it is clear that in reality, it is a search. And it has been said that the most desperate drama of the Beat Generation was to find a transcendent reality in which to believe, such as to supplant a conformist middle-class life. They are not part of a movement: they have no prospects, they have no plan to reach, nor an eschatology to pursue. There is no future, there is no past, there is only an immanent present, inexplicable, that only liberation from space and time can temporarily overcome.

The means to do so may be physiological (such as orgasm), or mystical (such as visions), or passionate (such as jazz), or artificial (such as drugs). Only by this momentary overcoming can one arrive at a poetic reality, together with a reality of life.

“[…] and I shambled after as usual as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes -Awww!-”

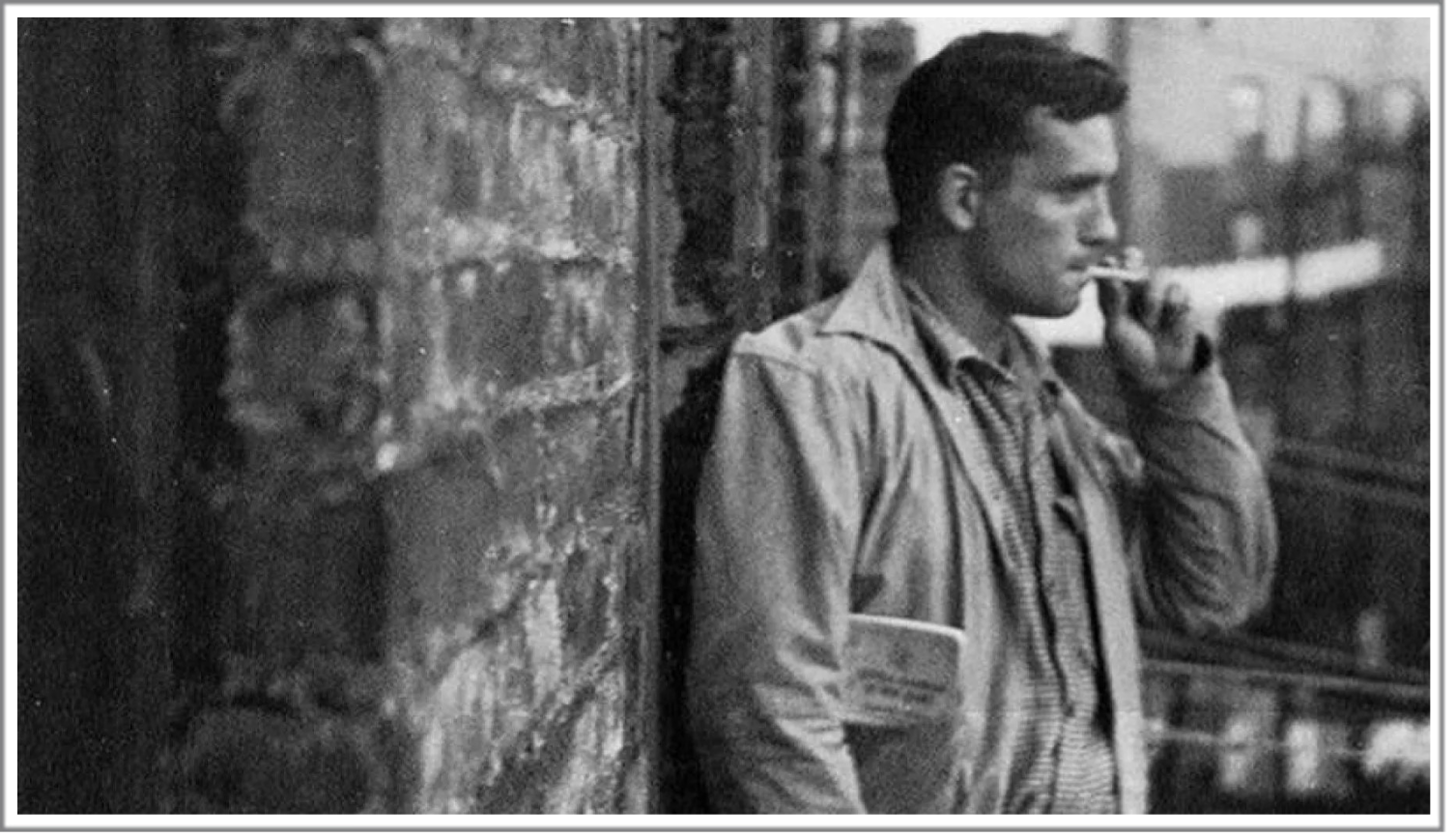

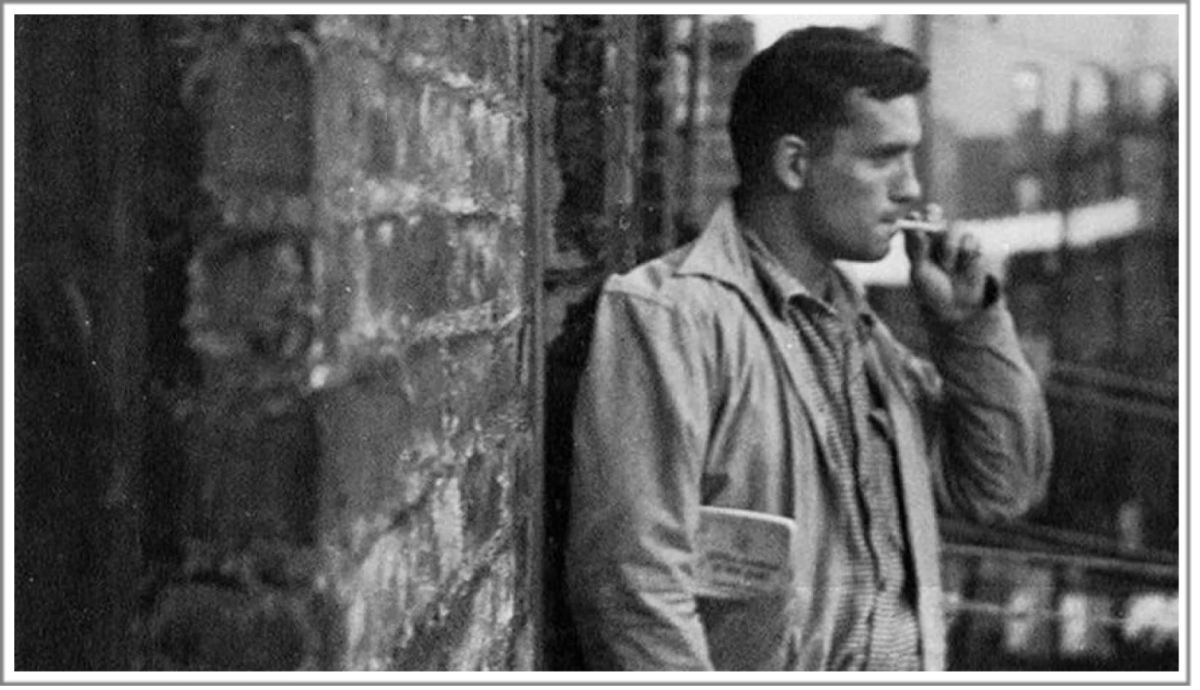

On the road, Jack Kerouac, 1957

In reality, the Beat Generation does not make a difference between religious and alcoholic exaltation, what matters is to feel freedom flow in them, independence, living and individual energy. They are extreme means, of course, but the children prefer to take the risk rather than face a stale, empty, meaningless, and perhaps ultimately worthless community life.

Their tormented search for a new moral reality, new answers to the questions of the world, make them a generation of mystics and philosophers: some are Catholics, others are Buddhists, and everyone believes in God. When a journalist asked Kerouac to whom he prayed, he replied: “I pray to my dead brother, my father, Buddha, Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. I pray to these five people”.

The identity they seek is an identity based on faith, whatever faith maybe, but which must be attained by the realization (and therefore discovery) of their personality. They rely on themselves to find, in themselves, a trace of transcendent values that can guide them on an even shorter, faster, futile, and tormented journey of life. So when they asked Jack Kerouac, “It‘s been said that the Beat Generation is a generation looking for something. What are you looking for?” He said, “God. I want God to show me his face”.

==================

The Ars Lumens blog is curated by Carl Kruse. The homepage is here.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com.

Asia Leonoardi has written about Bowie’s Alter Ego, Pop Art, Frida Kahlo, Brunelleschi and Lost Architecture.

The blog’s last post announced a photo exhibit in Berlin by Adele Schwab.

If on Pinterest stop by and say hello.

Kerouac’s ON THE ROAD made such an impression on me in college. Enough to get on the road and take a road trip across the United States. I didn’t find enlightment or much more of interest than from where I left, but that might be the fault of the traveler and none with the road.

I hear you. No matter where you go, there you are, supposedly said Buckaroo Banzai.

Carl Kruse

I also enjoyed On The Road. And Kerouac’s Dharma Bums.

I enjoyed both when I was in college though somehow they have faded for me over time. I hope that doesn’t mean I am falling into that category of folks that the Beats were running away from.

Carl Kruse

All good Kruse. They faded for me as well.

Susy

Thanks for stopping by Susy.

Carl Kruse