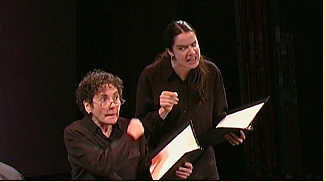

by Carl Kruse Ahoy people in Berlin! Niraj Welikala, a member of both the Oxford and Cambridge alumni societies in Berlin, founded a play-reading and theater group in Berlin last summer and is looking to expand the group to fellow thespians and those who love the theater. The group’s objective is recreational play reading and

Category: Acting

Art for Art’s Sake: Noh Theater in the Age of Images

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog This is a photograph of two women in front of a photograph of couples dancing. You do not know these women. What can we deduce from this image? Many a thing. The old woman is looking at the camera. She knows she is being watched.

When the Show is Over

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The mist has lifted, and life is back. It is an abyss, a swamp of unknowing and learning how to live without the glistening sheen of adrenaline that glosses over your eyes for the weeks and days preceding and encompassing a show. You lie flat,

Finding My Clown: A Distilling of the Human Condition

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The fundamental reality of creation is solitude. This is what Lecoq tells us, and, when I turned around and faced the audience, clothed with my red nose for the first time, I did indeed feel very alone. We had started doing clown the week before,

Acting and Art: Channeling Animals

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The studio floor is covered in bodies. They are curled and strewn and spread and sprawled, as though they were dead. But they are not. Some breathe shallowly, quickly, as if their hearts fluttered about like moths. Some breathe deeply, forcing air bull-like through their