by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Art’s Blog Before her face was associated with one of the most evocative works of art of all time, even before becoming the symbol of an incredible legal affair, Adele Bloch-Bauer was simply a beautiful woman. Born in 1881 in Vienna, Adele had grown up in the cultured

Tag: Carl Kruse Art Blog

What Does Art Cost -With Yury Kharchenko

by Carl Kruse On January 8, 2022 the Deutschlandfunk Kultur hyperlink – radio program invited our artist friend Yury Kharchenko to discuss the cost of art, both from a material and figurative perspective. The program was hosted by Michael Köhler and translated from German to English by Carl Kruse, who is responsible for any errors

Upcoming: Adele Schwab Photo Exhibit in Berlin

by Carl Kruse My friend Adele Schwab has organized a photo exhibit in Berlin on two dates: 19 November 2021 (Friday) from 21.00-22:30. 20 November 2021 (Saturday) from 17.00-18.30. Adele Schwab. Photograph from the artist’s website. Her exhibit is titled, “Seeing the Unseen” an audio visual project that attempts to make air “visible” and investigates

The Legacy of the Satyr

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The passing-down of literature fascinates me. I find something utterly awe-inducing in the ability of human language to convey a narrative generation after generation, and for us to have the knowledge and ingenuity to understand the importance of preserving great stories and characters. I suppose

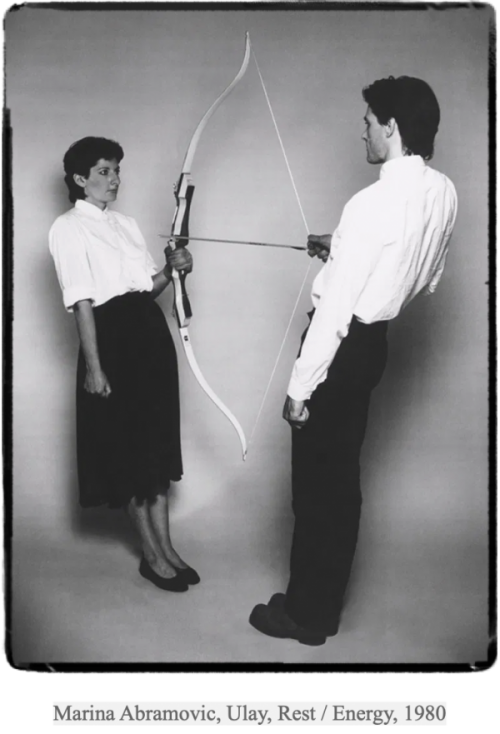

Marina Abramović, Grandmother of Performance Art

By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog This story begins with a woman standing motionless in a room. Half-naked, a trickle of blood dribbles on her breasts, her eyes swollen with tears, and a gun is aimed at her while surrounded by a group of men. This is not the scene from a crime

Frida Kahlo: Flowers Are Born From Mud

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog On 6 July 1907 in Mexico City, Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon was born to German parents who emigrated from Hungary. She claimed to be born in 1910, with the Revolution, with a new Mexico. Frida Kahlo is a revolution. An artistic revolution, a revolution

Are Memes Art?

by Vittorio Compagno for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The digital era gave birth to unique trends tied to the advent of the Internet. The source of many of these trends is as old as the internet itself, which is to say online forums. From these fountains of discussion, as in the ancient Greek “agorà,”

Thinking About Realism

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Realism tells tales like any other genre, and it is odd that we should be forced through much digression knowing that point. What I mean when I say Realism is the specific genre of fiction that wishes to imitate contemporary life in a ‘realistic’ manner. Realism

World of WearableArt: Blurring Boundaries in The Art World

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog There is often a perceived disparity between the words “fashion” and “art.” Many people fall at the feet of, say, a Gauguin, a Turner, or a Matisse, but upon hearing the word “fashion” quickly recede into their boots, or worse, scorn and sneer its name.

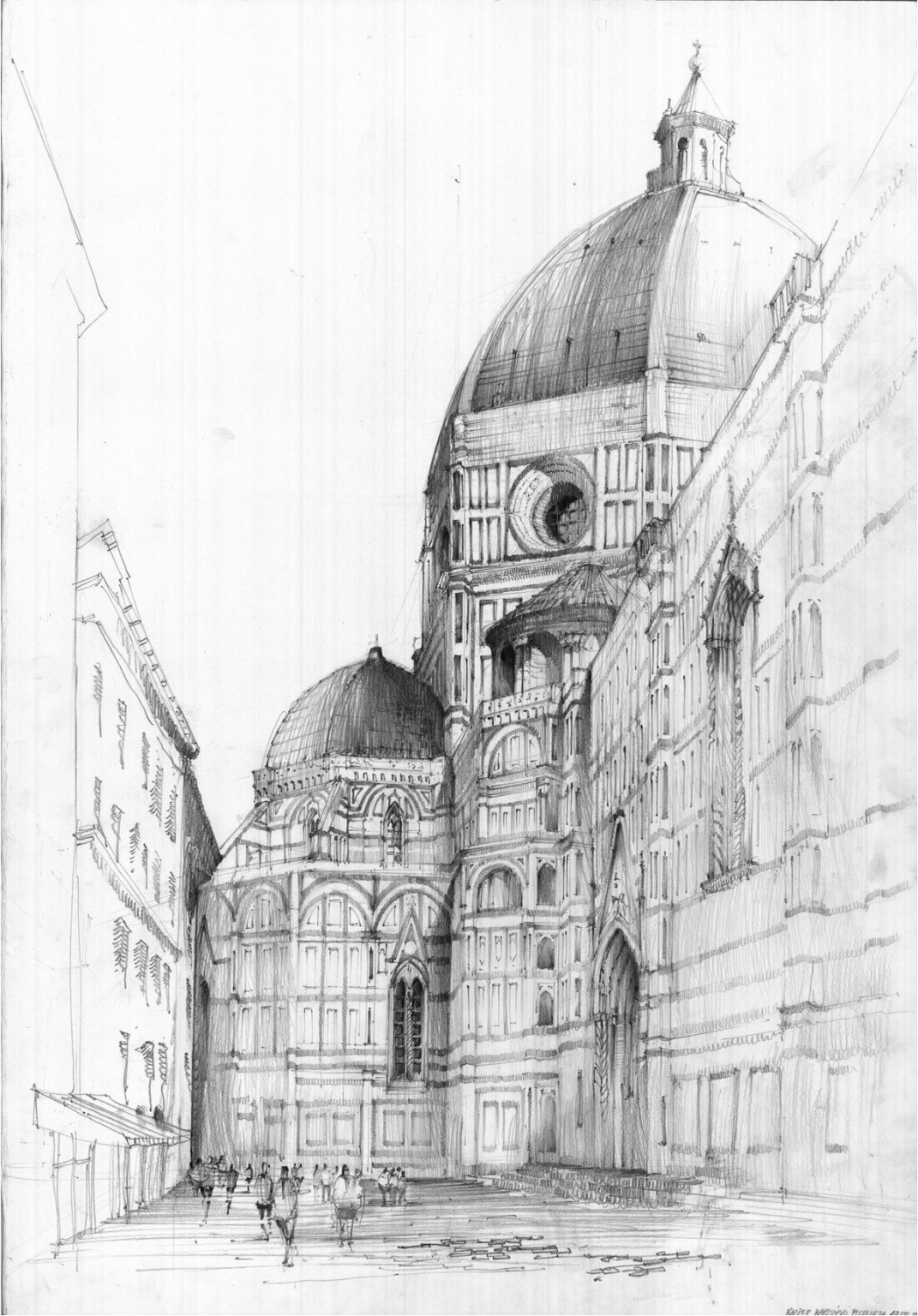

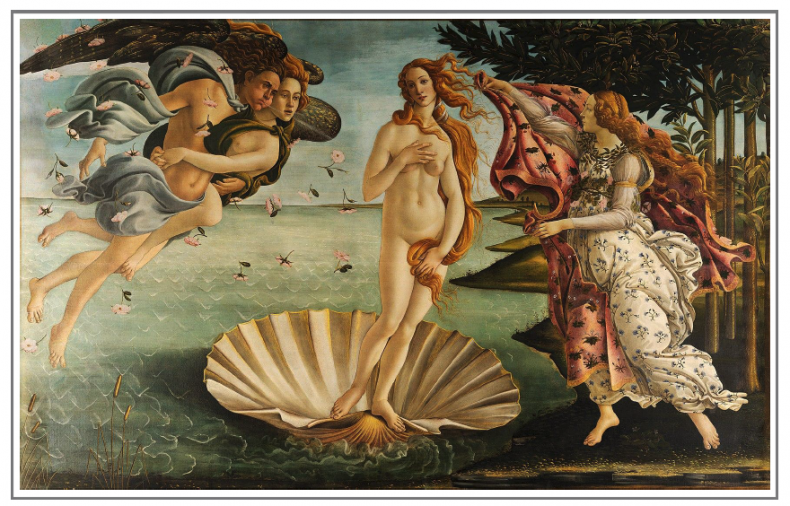

Simonetta Vespucci: Venus of the Renaissance

By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog In the church of Florence of San Salvatore Ognissanti, where the secular exponents of her family are exhibited, rests today the beautiful Simonetta Vespucci in her secular sleep. But there was a time when the prodigious beauty was the inspiring muse of major Renaissance artists, such