by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog in conjunction with the Ivy Circle is happy to forward an invitation from the Wharton Club of Germany and Austria for a visit to the studio of renowned artist Hubertus Hamm in Munich to take place March 12, 2025. The invitation follows:. We are delighted to invite

Tag: Carl Kruse Arts Blog

Masa Daiko at Samurai Museum in Berlin

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog invites all to a performance of Masa-Daiko, one of the best Japanese drumming groups in Europe, performing traditional Japanese Taiko to take place Saturday, March 8 starting at 7:30 p.m. at the Samurai Museum in Berlin.. The eight musicians of Masa-Daiko perform both traditional Japanese pieces and

Jade Cassidy Art Exhibit in Berlin

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog in conjunction with the Ivy Circle Berlin is happy to invite all to an art exhibit of artist Jade Cassidy taking place on Wednesday, February 12, 2025 from 6-9 p.m. at the Quantum Gallery on Kurfürstendamm 210 in West Berlin. The event will feature complimentary champagne from

In Memoriam – David Lynch

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog David Lynch’s work in both television and film mesmerised his viewers. With originality, a purity of vision, lovers will be matched by detractors. That is no bad thing – not in the superficial ‘any attention is good attention’, but in the challenge it poses. Stop Making

Bowie Went To Berlin

by Hazel Anna Rogerts for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Bowie went to Berlin to escape. That is how it seems. We weren’t there, most of us, so we don’t know. There is talk about cocaine, about notoriety, about noise. But we weren’t there, so we don’t know. It makes a good story, doesn’t it?

DANCAE Performs in Berlin

by Carl Kruse The Dancae dance company, headed by friend of the Carl Kruse arts Blog Soraya Schulthess has two upcoming performances in the Charlottenburg neighborhood of Berlin. The performances explore the tension between our primal instincts and the constraints of the alienating, competitive pressures of modern life. The event takes place at the Quantum

Tour of Boros Art Bunker In Berlin

By Carl Kruse The Cambridge Society invites members of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog to a private tour of the iconoclastic Boros Bunker art collection in Berlin. The event also is co-sponsored by the Ivy Circle in Berlin (of which Carl Kruse is the director). Spread over 3,000 sq m of a converted air-raid bunker,

Art Brunch in Berlin with Artist Helena Kauppila

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog in conjunction with the Ivy Circle Berlin would like to invite all to its second Art Brunch at the studio of Helena Kauppila, on Saturday, October 5, 2024, starting at 11:45 am on the fourth floor of Ackerstrasse 81, 13355 Berlin There will be a welcome and

On Rising Theater Ticket Prices

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog In May of 2024, Jamie Lloyd’s production of Romeo & Juliet starring Tom Holland and Francesca Amewudah-Rivers sold its first batch of tickets in two hours. A friend of mine told me that he and his friends had all grouped together with their laptops open,

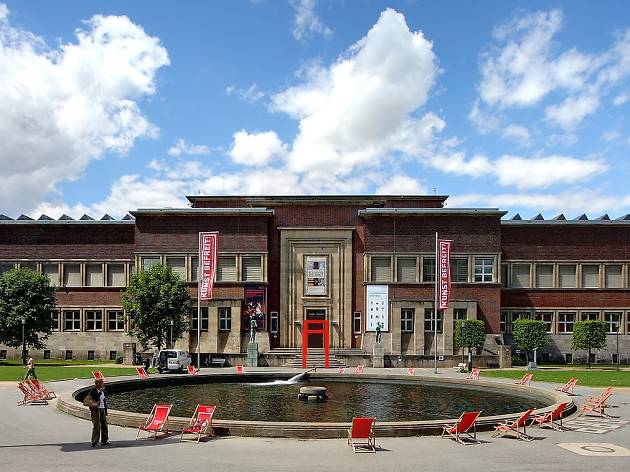

Visit to Gerhard Richter Exhibit at Museum Kuntspalast

By Carl Kruse The German Friends of the London School of Economics (LSE) invite members of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog to a visit to the exhibition of “Gerhard Richter. Hidden Gems. Works from Rhenish Private Collections” at the Museum Kuntspalast in Düsseldorf on Sunday, 15 September 2025 at 2:15pm. The major autumn exhibition at