By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Member of the Magnum, Steve McCurry graduated in 1974 in Cinematography and Theater from the University of Pennsylvania. He began work as a freelance photographer in the late 1970s, dispatching reports from India and Afghanistan, the countries with which his work is most identified. The turning

Month: November 2020

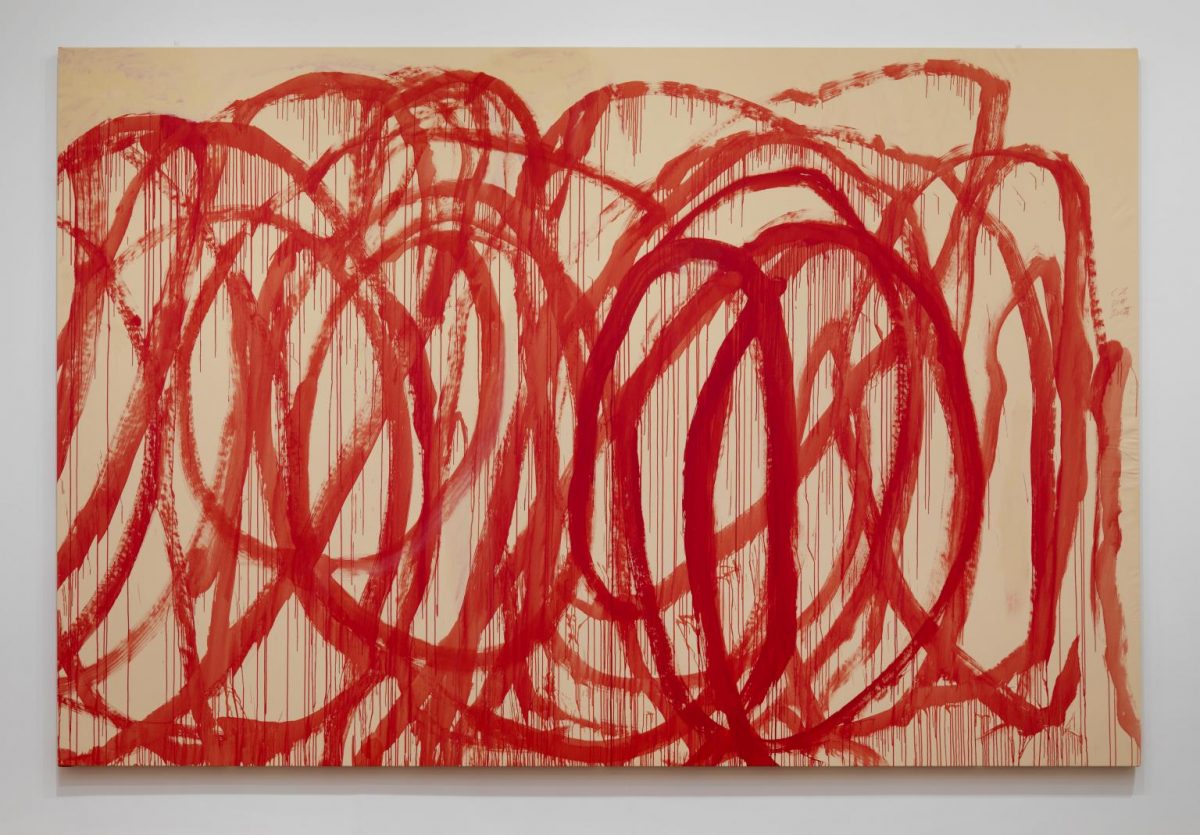

More on Action Painting

One of our readers wanted more on action painting, the technique highlighted in our previous post on Jackson Pollock, and our resident writer Asia Leonardi — who wrote the original Pollock piece — was happy to oblige with a quick survey. Take it away Asia! Action painting is as an immediate, free, spontaneous painting in

When did we Stop Criticizing Art?

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog When I was around 13, I visited the Tate Gallery at the Liverpool Docks in Northern England primarily to see an exhibition of J.M.W. Turner and Cy Twombly, a starkly contrasting set of artists and the latter of which I actually had next-to-no prior knowledge

Infinite Worlds Upside Down – The Interior Landscapes of Maurits Cornelis Escher

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The graphic art of Maurits Cornelis Escher is different from that of any other artist, instantly recognizable to millions of people around the world, representing an always compelling combination of art and mathematics. Escher’s world, which explores issues of infinity and paradox, of impossible geometry and