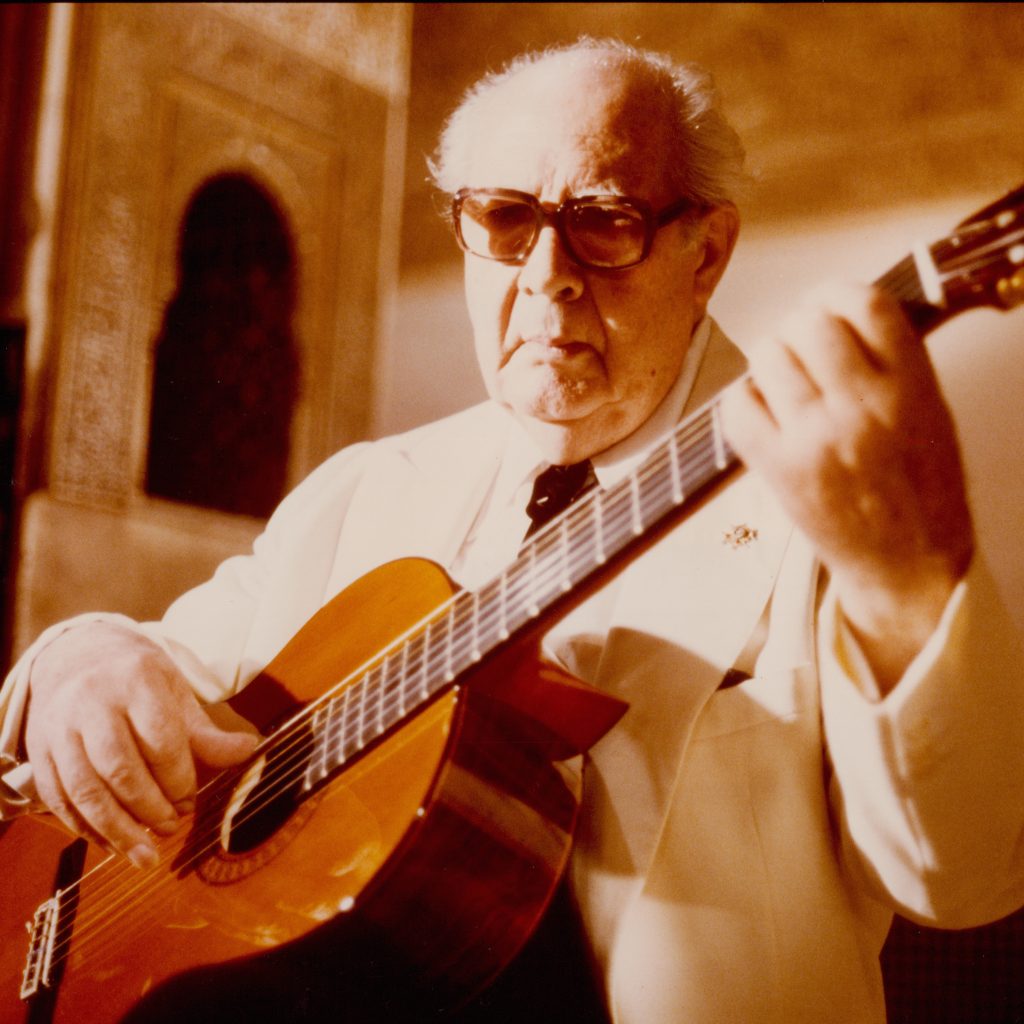

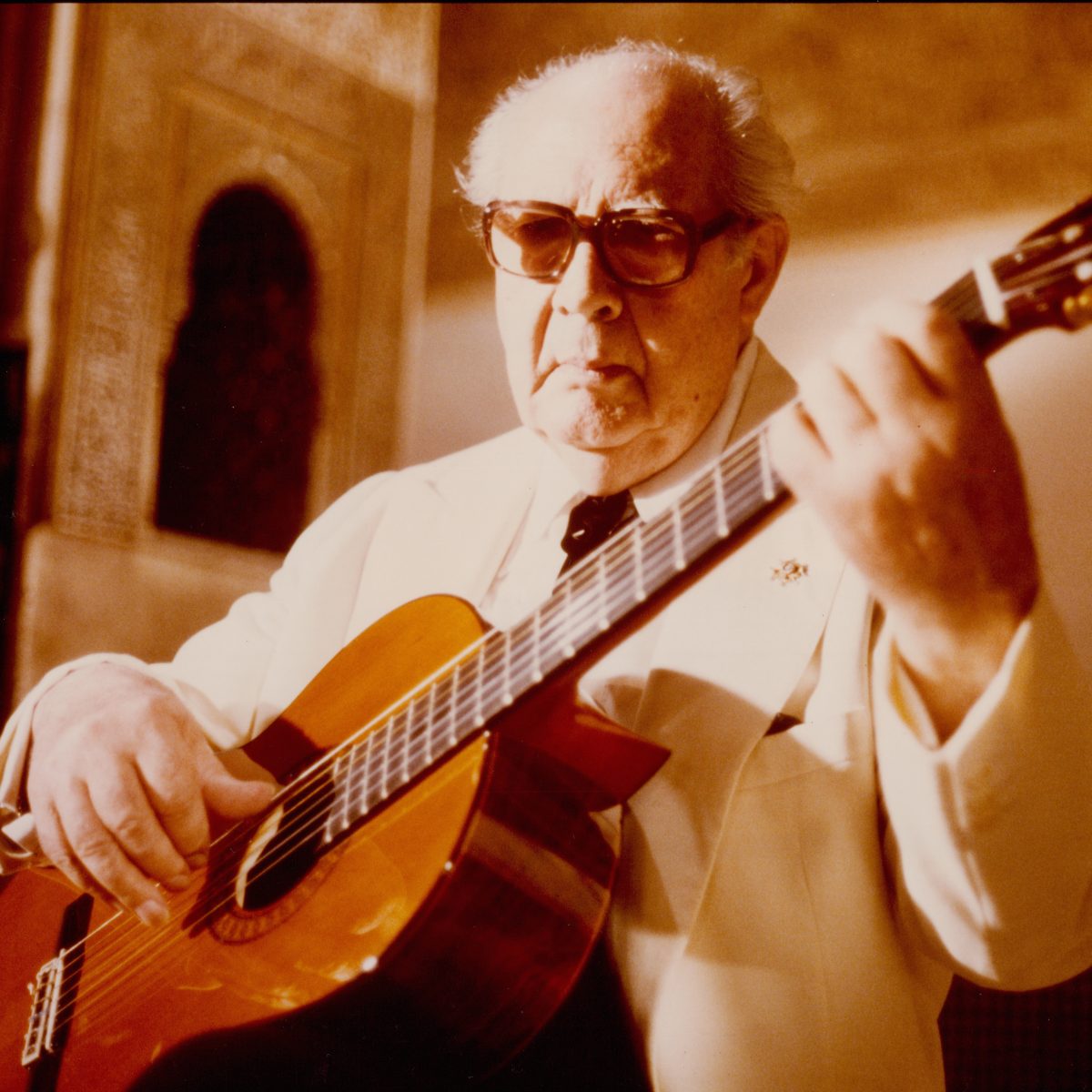

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

The seventy-four-year-old maestro sits plump in a large wicker chair. His gut ovals as he looks out from his balcony towards the Mediterranean Sea. His home is large upon the hill, overlooking an olive grove which blinks out the Andalusian heat. Close by is Granada, the spiritual birth place of Andres Segovia.

“This will be the first time in thirty-five years that I have spent a single summer in one place” – not pensively, but as if harboring a certain emotional depth, he slowly walks along the balcony where a young shepherd dog jumps up to greet him. The man offers his forearm for the dog to playfully wrap its jaws around. The balcony extends along the perimeter of the house, larger than the man expected: “when they sent me the plans, I was very busy, I picked what I thought to be the larger, not looking at the scale; I was not expecting this monster”.

In this summer of rest, casually strolling through the murmuring sound of water that envelops Granada – the city cut into a mountain with the blend of Moorish intricacy and the tiles of houses which bloom in the sun – Segovia muses on how a mere boy could have left his life here: “Destiny only” he emphasizes.

Segovia was around eight when he took an interest in music, taking lessons in both the piano and violin. His experience with his teachers, whom he called ‘mediocre’, even at that age, as the story goes, reveals a characteristic of Segovia that never strayed far from him: an un-denying sense that the musician had to live the music.

It was when he heard average guitar players, be it on the street or in the bars of Granada, that he became fixed with what he called its ‘melancholy’ nature. Melancholy was a distinct representation for Segovia, and the word should not be misread as ‘depression’. The feeling seemed to incite in him, intuitively, a sensitivity to what the guitar was capable of. Thus, distancing himself from the ‘mediocrity’ of his local teachers, he became both student and teacher, working towards a closer connection with the instrument.

The guitar became a way of dialoguing with the heart, much like the prose-poem of Juan Jimenez, Platero y Yo, which Segovia admired. Platero y Yo tells of the eponymous Donkey, who serves as a constant companion and listener to the poet’s observations and confessions. The poet believes Platero can understand all that is said to him by the fact of his constancy, his tenderness, and his innocence. Like Platero, the guitar for Segovia seemed to transcribe the inner world into a living statement.

Cover art work to Segovia’s 1963 “Platero y Yo” in English, “Platero and I.”

Segovia’s passion and skill lead him to an aspiration of situating the guitar amongst the canon of concert instruments (piano, violin etc.). Guitar was then considered not above a parlor performance, despite the contemporary efforts, and tours, of Miguel Llobet and Francisco Tarrega. They were among the classical guitarists Segovia respected, and although rumored to be an adequate flamenco player, and an admirer of Flamenco culture, Segovia saw the guitar as a conduit for classical compositions and distanced himself from the folk-influenced Flamenco.

It was obvious to Segovia that, despite his Spanish contemporaries, the guitar needed rescuing and securing; not only that, it needed to be passionately understood as an instrument: “I had to rescue the guitar twice: first from the noisy hands of the Flamenco players, and secondly from the devoted incompetence that was given to the guitar in the nineteenth century”. The first rescue involved Segovia’s self-taught precision in playing, and the second meant scouring through, and transcribing, pieces for the guitar which would show off its slumbering, enchanting dynamics.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, he had traveled to Europe and then to South America giving performances of a revitalized repertoire that increasingly drew the guitar into focus: a short man, left leg slightly raised, and cradled in his lap, the varying strains of a wooden guitar. This kind of guitar had only taken its form since the mid-nineteenth century. The luthier Antonio de Torres had perfected the modern guitar. However, in the first few decades of the twentieth century, Segovia was cradling another name: Ramirez.

Before his rise to fame, Segovia had met the luthier responsible for the sound, Jose Ramirez. Although dressed lavishly, as Segovia tells us, like a dandy, he was poor. He was in Madrid, playing in Tarrega’s city. After striking up a friendship with Ramirez and performing for him, Ramirez handed him his most diligently crafted guitar. Thinking he wanted to hear him play it, he did so. After the piece was played, Ramirez refused to take it back. “but I have no money” Segovia explained. “I know”, spoke Ramirez, “pay me back in another way, play that music around the world”.

Luthier Jose Ramirez, whose guitars are still played the world over.

Segovia’s fulfillment of the promise awakened more possibilities in the luthier’s craft. The guitar’s awakening, especially in the concert hall, gave impetus to greater developments in the instrument: to make the guitar ring louder; to emphasize the intricacies of the dynamics which existed within the hollow body. It was a sustained effort amongst luthiers to concert new techniques for expression, and undeniably helped to shape the evolution of the guitar.

Much of what we take for granted on, and about, the guitar is realized in Segovia’s mission to obtain respect and admiration for the guitar. He speaks of the guitar as possessing all of the orchestra, only in minute forms. Tonality can differ greatly according to where the right hand is placed; it can imitate brass or the cello, beckoning attention or intimacy; and, it is polyphonic. The master of the guitar needs to control these dynamics to evoke the quality of what the guitar is.

The problem was, according to Segovia, is that those who had composed for guitar in the past did not understand the intricacy of the instrument. It was only Fernando Sor at the beginning of the nineteenth century and Francisco Tarrega at the end thereof. Segovia felt himself responsible to transcribe the music of great composers, to show the guitar could not only replicate the concert instruments, but evoke beauty in a new way. This led him to Bach, Albeniz, Granados, Handel and countless others. Increasing the repertoire exposed the guitar as an incredibly versatile and expressive instrument. Segovia and his guitar were serving as a conduit for the music of the past and present.

Segovia’s sensitivity towards the guitar as a medium of melancholy, of beauty, led him to found his own distinctive performance style. Although, in the beginning, the students of Tarrega thought him idiosyncratic at best, they would ultimately be silenced by what became known as the ‘Segovia hush’: amazement, respect, and awareness of grace.

Thus established, Segovia pushed further and began to ask contemporary composers to write for the guitar. Manuel Falla, Alexandre Tansman, Castlenuovo-Tedesco, Manuel Ponce, and many others took up the challenge. Writing for any instrument, of course, means intimately knowing the range and dynamics of that instrument. This call to the contemporaries led not only to an increased repertoire, but a heightened focus on what the guitar could do – each testing the performative style of Segovia and expanding his vision of musicality. Some virtuosos, so enthused by Segovia, took it upon themselves to write for him unasked, here we note the famous 12 Etudes by Villa-Llobos.

Segovia’s eight decades of performing permeates through the legacy of the guitar, and music itself. He was a source for many new compositions, and he was a translator of old into the new. Segovia certainly had a vision for what the guitar should transmit: Latin-based, Baroque, and Romantic pieces. This meant modern atonal, experimental pieces written expressly for Segovia were denied entry; a purist often functions by restrictions. Always happy to steal concert goers away from The Beatles, often lamenting the rise of the electric guitar, Segovia functioned as a counter to much of the popular music of the twentieth century.

Even so, the spectacle of Segovia produced a sustained image of the guitar’s inherent melancholy. Just as his obliviousness to check the scale of the house which was being built for him, his work spawned a web of influence too large for him to realise. His personal affectations were, for the next generation, something to either improve upon or rebel against. This could mean new ways of utilising the guitar or excepting new pieces into the repertoire. Either way, the guitar keeps moving; the vision of its beauty still stands.

When asked, in 1967, if he knew when he was going to retire, he responded with the enigmatic line: “Depending upon my health, yes, I will have to retire someday, but I am not to be retired”. We are brought into a state of reverie by this. Is it by listening to the guitar, we remember something of what Segovia lived for? Something of that melancholy, that intimate and wholly human expressiveness which permeated so much of his work? Or that Segovia will continue existing as his repertoire and music continued to be played, and in all his offspring in whatever form who continue to explore the strange complexity of the guitar, who feel something akin to what the maestro felt when he said “to play the guitar is to dream with music”?

=========

The blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.net

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Fraser Hibbitt include the Art Of Atari and Realism.

The blog’s last post was on the Beat Generation.

Carl Kruse and his music are on Soundcloud.

Segovia! Such an inspiration for anyone who picks up a guitar.

OMG I love Segovia. No greater guitar player or re-arranger evah!

Yes, yes, yes.

Carl Kruse

Does anything sound has elegant has a classical guitar. Maybe the cello?

Both cello and guitar — fantastic.

LONG LIVE SEGOVIA

Classical guitar is my favorite instrument. To listen to that is. I cannot play.

I love it as well Anetta.

Carl Kruse

I am listening to “Platero y Yo” right now.

So much goodness there. Thanks for sharing.

Carl Kruse

segovia best guitar player and re-arranger in history. where the classical guitar if not him.

I am happy to see so many Segovia fans. I am 22 and not one of my friends knows who he is.