by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

The Estorick Gallery in London is now dedicating four of its rooms to Giorgio Morandi. These are not the grand spaces you find in places like the National Gallery or the Louvre; the gallery is a converted Georgian town house and it is impossible to become overwhelmed by these rooms that you can walk across in less than ten steps. So it is with the building: floor one, two rooms; floor two, two rooms; floor three, two rooms. Morandi has two floors and they are mostly Still-Life, that odd and obvious genre that extends back to the Greeks.

The Estorick Gallery in London

It shouldn’t be glossed over that the Still-Life is held to art as the etude is held to musical composition and style; it is a way of training the eye for compositional features, of conditioning the sensibilities to the pictorial complexities that arise from the placement of objects. You get the Still-Life showing up in every significant artistic movement of history, and it is still a healthy form today. It is the most ready and versatile form for any kind of drawing class and a reliable form for an artist to showcase their skill. We all know and live around the objects depicted that we intuit their forms subconsciously; we know how to inhabit the picture, and being reminded of the beauty that is inherent in a vase is something strikingly pleasurable.

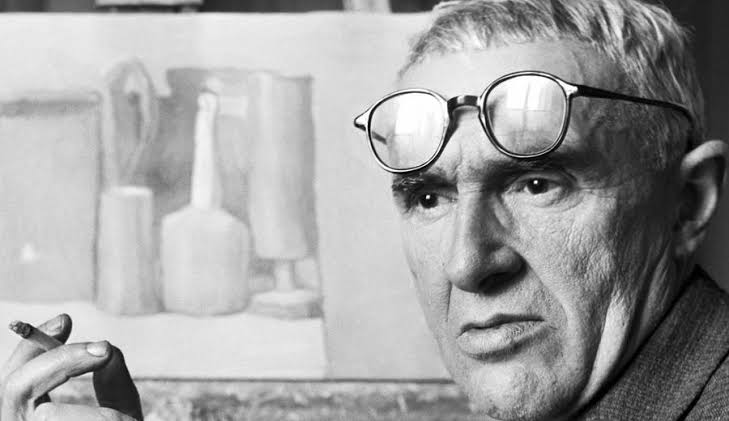

Giorgio Morandi

This pleasure of viewing and seeing what we know may partly explain the enduring fascination with depicting inanimate objects, fruits, flowers, dead animals etc. for these past two millennia. In 5th century B.C., so the story goes, Zeuxis and Parrhasius competed to determine who was truly the greater artist. When Zeuxis revealed his depiction of a bunch of grapes, birds were even fooled and flew down to attempt a peck; Parrhasius then asked Zeuxis to do the honours of drawing the curtain to reveal his own painting, however, Zeuxis was unable, despite trying, as Parrhasius painting was of the curtain itself. Zeuxis bested the birds and Parrhasius bested the man, giving that imitation to the extent of “tricking” the other was prize-worthy.

This desire to imitate nature can be an end in itself – it appears so for the Greeks – even though the composition, by definition, is far from natural, and so too are all those other peculiar features inherent in the art that are so dislike nature: the mechanical side which presents the image, i.e., the medium, the frame. All these elements are, naturally, withheld from perception’s attention in order to deliver the art; it is actually their function, and the Still-Life seems able to adapt, for whatever reason, century by century to this need to close in perception on the inanimate.

The Dutch Vanitas painting of the 17th century was a Still-Life genre aiming at something different from imitating nature to imitate nature. It was reminding the viewer that life is short, that you ought to fill it with good works; all your vain attempts to secure earthly fame and prestige will come to an end: remember this transient life is nothing in comparison to the life beyond. Here we see the low-lit interiors, the somber hues, the skulls, the tomes piled up with a lute to boot, and the fruit is beginning to rot; it is all depicted perfectly, actually beautifully, and the detail is exquisite: you cannot take your eyes away from this earthly share which is all you know; Vanitas presents a beautiful piece of mockery.

Vanitas was the Still-Life imbued with the troubled Christian spirit of the 17th century, and one who is willing may want to compare it with the Greek manner of viewing such imitations. It does seem, moving on through to Morandi’s celebrated career as a predominantly Still-Life painter, that these two forces (the pleasure of imitating nature and nature’s imitation’s ability to signify beyond itself) help pave the way to a new recognition of the Still-Life. Where it ended had much to do with perception for perception’s sake – that is no light thing – and a silent praise of objects.

Still-Life can often remind us that we have not been paying much attention to the objects around us. We grip and hold, pour and sate ourselves on things that are, when presented to us, capable of a complexity and beauty above their function (See Cézanne’s Apples). A Modernist like Picasso or Leger would confound with their chaotic Still-Life images; the planes and angles have all been deconstructed, nothing will come into focus. The experience of a Cubist Still-Life is an experience that is difficult, if not impossible, to replicate in lived experience – and the use of the purely intellectual faculty here seems to lack something. Go to your vase, look at it from every angle and you can understand how many possibilities there could be, and how does this change with the introduction of one other object? In the Cubist Still-Life, there begins to form a fragmented abstraction of all the possibilities, as though the atoms are lining up to be formed and what we get is a snapshot of the process.

This ‘processional’ technique was not limited to the Still-Life, but Still-Life proved welcoming to the new experiments of Modernism; Still-Life even fared well with Surrealism and De Chirico’s “Metaphysical Art”, though it is perhaps not the exemplary form of these artistic statements. It is something to wonder at that, in a century of such experimentation, such “liberation from traditional forms and idea”, Morandi made his name through decidedly simple Still-Life images. Seeing a collection of his work, you do see why they are often described as “silent perfection”, or as “exquisite poetry”. Morandi’s interest is not in strict imitation of nature, instead, the objects seem suspended in no place – Morandi had learned from De Chirico, but instead of the obscurity of image and that strikingly clear technique which would characterise a Surrealist like Dali or Magritte, Morandi reduces things to an awkwardness of technique and a simplicity of colour.

Still life by Giorgio Morandi

Morandi’s choice of objects rarely alters either. It is always the vases, bottles, and bowls again and again, each time working towards a balance of tone and composition. There is a little else to it; the paintings are hyper-focused for the express purpose of these few and simple objects; there is no background, no lavish display, only this twilight feeling of things coming to rest. There doesn’t appear to be any “outside” message, no fooling the birds; it is only (only, not as in merely) a quiet simplicity in an everyday object, and after the cubist foray, things appear manageable and well; you don’t need to look any further than this one concentrated image. The Still-Life, under Morandi, cannot be recognized as just another table in a home but as a balance of mood that objects lend to a home, a recognition of the things that inform the most simple of our daily rituals, and the perception to appreciate it.

=============

The Carl Kruse Arts Blog homepage.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Hazel include Art for Art’s Sake, When The Show is Over, What I have Learned About Running, and What Does it Mean to be Wealthy.

The Carl Kruse Bio is here.