by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

One day in 1977, a young girl entered the “Maldoror” art gallery in Rome, handed the owner a gray box and exclaimed: “I’m a photographer!” She is not yet twenty and her name is Francesca Woodman.

Born in Denver in April 1958, Francesca was the daughter of a potter and a painter. Her father George initiated her into photography, giving her a camera he never used, and which he would return to after his daughter’s premature death in 1983.

“We were all artists, and all our friends were artists themselves,” says George Woodman in an interview. “It was therefore something normal for Francesca. But she didn’t try what we already did. She immediately went her way.” He gave to her that camera when Francesca was only 13 years old and was about to start her first art school – more or less the age in which today you get your first smartphone, but at that time starting to photograph so early meant being precocious, even for a daughter of Art.

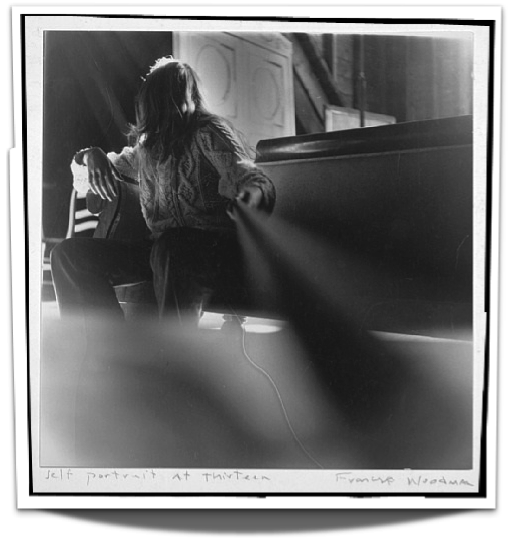

Her first self-portrait dates to 1972 (“Self-portrait at 13,” Boulder, Colorado), a square shot, in a soft blackened white and set indoors, in which emerges a strong relationship of the body of the subject against the surrounding space, thanks to the play of perspectives. As in selfies you can often see the arm of someone holding a smartphone or a camera to shoot, here you see — and occupies half the scene — the wire that connects the camera to the self-timer button. Francesca’s face is partially hidden by her hair, in a play of the visible with the hidden that will continue to captivate her throughout most of her future experiments. This work inaugurates all of her considerable production with precise rules, even if only a small part of these are known. Incredibly prolific, Francesca Woodman in the only eight years in which she worked with photography produced ten thousand negatives and 800 prints before taking her own life. Only about a hundred of these images have been published and exhibited.

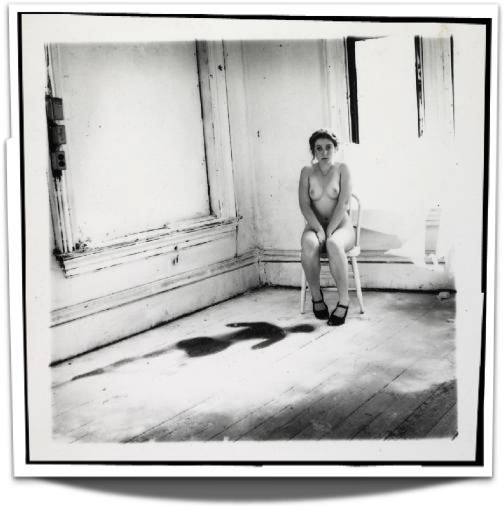

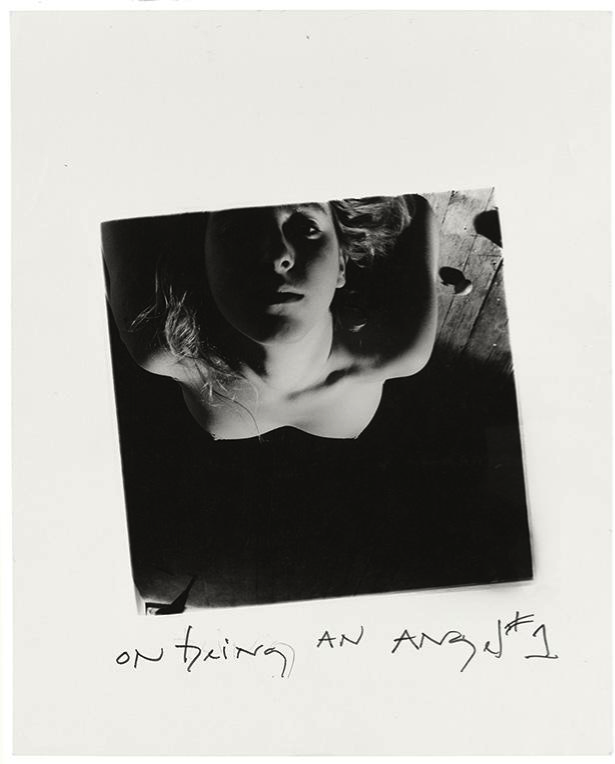

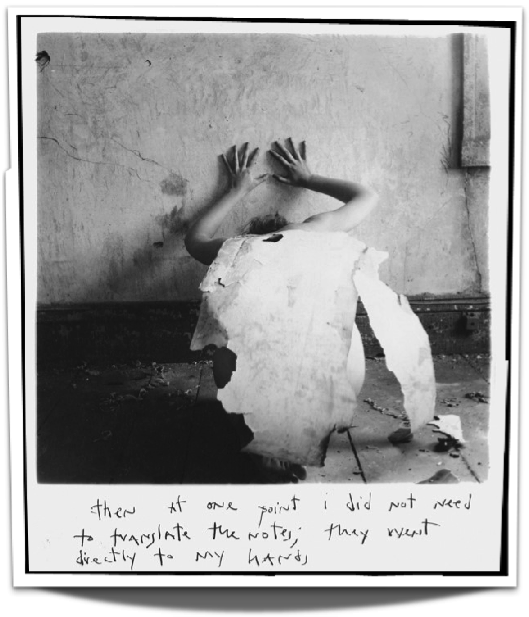

Francesca Woodman used herself and various objects, even symbolic ones, to explore themes concerning the adolescence she was going through: the question of identity and body image, relationships and sexuality, alienation, and isolation. “It’s a question of convenience, I’m always available” the photographer replied lightly with a touch of irony to those who asked why she always chose to be the subject of her photos.

To find answers about her identity, Francesca Woodman often strips, literally, and naturally photographs her naked body, which is ever-changing as she progresses through adolescence to adulthood, and which is never quite resolved, often hidden behind furniture and objects, wallpaper, plants mirrors. This staging of the nude never comes across as with sexual intent, but more functional in the exploration of the relationship of full and empty in space, between the presence and the absence of the body and the status of the self, which is both subject and object, conscious, explorable, purely material, beyond any transcendence. There is no intent of celebration, but a desire for communion with the world and with nature that is accomplished in transfiguring oneself and becoming a work of art.

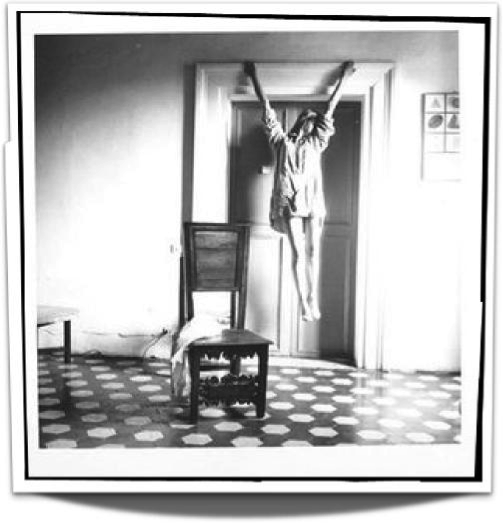

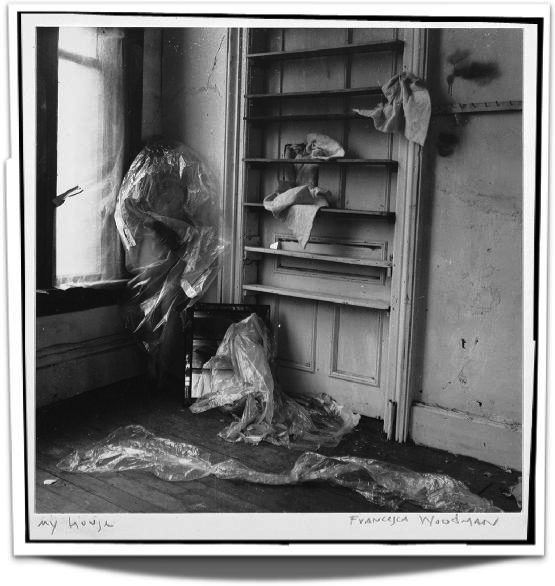

Francesca experimented not just in composition, but also, on a more technical level, with the long exposure modes of the camera, seen as a tool for making possible one’s presence in the negative, capturing movement, creating ghosts, a mysterious atmosphere, and playing with time, challenging its limits: even if the photographs were taken by her during the 70s, thanks to the settings, between abandoned interiors and peeling walls, and to the timeless clothes, which could belong to other eras, to her taste for the image and black and white, they seem placed in an atemporal moment, suspended between past and present.

In 1975 Francesca Woodman attended and graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD): her career had already begun and her self-taught training already advanced, and here she was able to stand out among her classmates, recognized by all as a sort of natural star with a more than a promising future. After graduation, she moved to New York with the desire to prove herself, and launch her career, but providing for herself and getting recognition turned out to be difficult for her. She held various jobs, from secretary to assistant to photographers, to model, while sending her portfolio of self-portraits to galleries and fashion magazines in the hope of being published. However, the positive feedback was slow to arrive, thanks to the loss of attention for the photographic medium towards the end of the 70’s, and the fierce competition common in a big city like New York, where too many tried to make their dreams come true.

This precariousness and the difficulty in establishing herself, after the school years in which her precocious talent was recognized and exalted by everyone, slowly led her to depression, until the National Endowment for the Arts — a U.S. federal agency that offers support to the most promising artistic projects — refused her request to obtain funds and in the autumn of 1980, Francesca attempted suicide for the first time, without success. “I have standards,” she wrote a few weeks later to a former classmate in Rhode Island, “and my life, at this point, is like an old coffee ground, and I’d rather die young, leaving behind a series of succeeding works, some jobs, my friendship with you and others … intact, instead of letting these delicate things vanish”.

The great hopes, combined with the impatience of youth, made the rejections received in the New York years unbearable and a few months later, in January 1981, Francesca took her life at the age of 22. Although Woodman’s self-portraits are not narcissistic products, the artist’s ultimate goal obviously could only be to live off her art, to be recognized, a feat in which her parents had succeeded before her. “She was much more sophisticated than a lot of us,” says Betsy Berge, her friend, journalist, and writer. “She was 21 and many were jealous of her talent. When you are twenty, everything seems very urgent. You think you have to achieve fame in 20 seconds, especially in her case, having started to do a really good job since she was 14. There was a lot of pressure on her”. The recognition she sought came shortly after, posthumously: the first exhibition was organized by Ann Gabhart, director of the Wellesley College Museum, in 1986, followed by a critical text by Rosalind Krauss and Abigail Solomon-Godeau. Immediately after, her work began traveling the United States, arriving in Europe in the early 1990s. Without being able to witness it, with her self-portraits, which we take so much for granted today, and the obsessive research of the self that belongs to everyone in the years in which one becomes an adult, Francesca Woodman has managed to change the history of photography.

Homepage: https://carlkruse.net

For another take on Francesca Woodman, see a review of “The Long Exposure of Francesca Woodman.”

The blog’s earlier snippet on Jack Delano is here.

Contact: CARL at CARLKRUSE dot COM

An old, old Carl Kruse Blog is here.

Well done Asia! Such a beautiful expose of Francesca Woodman.

I thought so too. Thanks for swinging by Tigerlilly.

– Carl Kruse

Thank you for introducing me to the work of Francesca Woodman.

Such a talent whose life ended way too early.

Certainly, a beautiful start whose light was extinguished too soon.

Carl Kruse