by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog

The stage is set. Three pyramids built up of myriad buildings and angles forge forth unto the screen. Spotlights dance in symmetrical lines, lighting up sections of the structures like a stage. The buildings blur into three black pieces of machinery plunging up and down, then these blur and a montage begins showing cogs and valves and compressors and axles whirring around and turning and grinding. The screen dissolves and we are shown a clock with numbers from 1-10. The hour of 10 is about to strike. Another image of cogs churning covers the screen. The second-hand ticks forward and finally hits the hour. The image switches to another scene where a jumble of pipes sits amongst a cityscape, this time ta view of the ‘Below’ – the worker’s city (the first city was that of the above-ground). These pipes begin bursting with clouds of steam from every hole. The screen turns black, reading the words ‘Shift Change.’

A new scene. Crowds of workers clothed in black overalls stand in rigid lines behind a gate to the left of the screen, and, to the right, another crowd of workers stands in front of a separate gate. Each gate lifts, and the workers on the left walk forwards to begin their shift. The workers on the right walk towards the other gate to rest briefly before they must work again. These men move like puppets, mechanically swaying side to side in unison as they shuffle. Their heads are bowed, and each man is indistinguishable from the next. They are the tools of the machine, the people who hold up the city from deep below the earth’s surface while the rich dine and drink and dance and merry away the hours. This is the introduction to Fritz Lang’s 1927 film, Metropolis.

Workers change shift. METROPOLIS

It had been some time since I had watched a silent film when I came around to watching Metropolis. Though to call such a film ‘silent’ seems to diminish the visual and philosophical noise that perpetuates the entire 153 minutes it runs for. Furthermore, the film is near-constantly accompanied by the haunting militaristic soundtrack of Gottfried Huppertz, so to call this movie silent is somewhat inaccurate in all senses of the word. The last silent film I had watched prior to Metropolis was The Artist, Michel Hazanvicius’ 2011 part-talkie (whereupon sparing dialogue is used in an otherwise silent movie) black-and-white picture made in the style of a 1920s Hollywood silent film, full of romance and hilarity and warmth – a world away from Lang’s dystopia.

I recently learned that I have been accepted for an MA Acting degree program at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, during which I will have the opportunity to experiment with different theatrical techniques from various acting theorists, predominantly those working during the twentieth century. Among these myriad approaches to learning the art of acting, there is one theorist who I am most excited to discover: Jacques Lecoq. Lecoq worked primarily in the realm of physical theatre (using movement to tell stories, as opposed to words). His method involves the use of six different types of mask – the neutral mask, larval mask, expressive mask, commedia mask, half mask, and finally the clown’s eponymous red nose – to encourage his students to act from a base of ‘newness’ or ‘unknowing’, as the mask works as a blank canvas upon which an actor can express themselves playfully and openly. The final stage of mask work, the red nose, is the stage at which the student may finally discover their own unique ‘clown’, because it allows them to finally use their face to express their emotions and thus to communicate through facial AND physical mime.

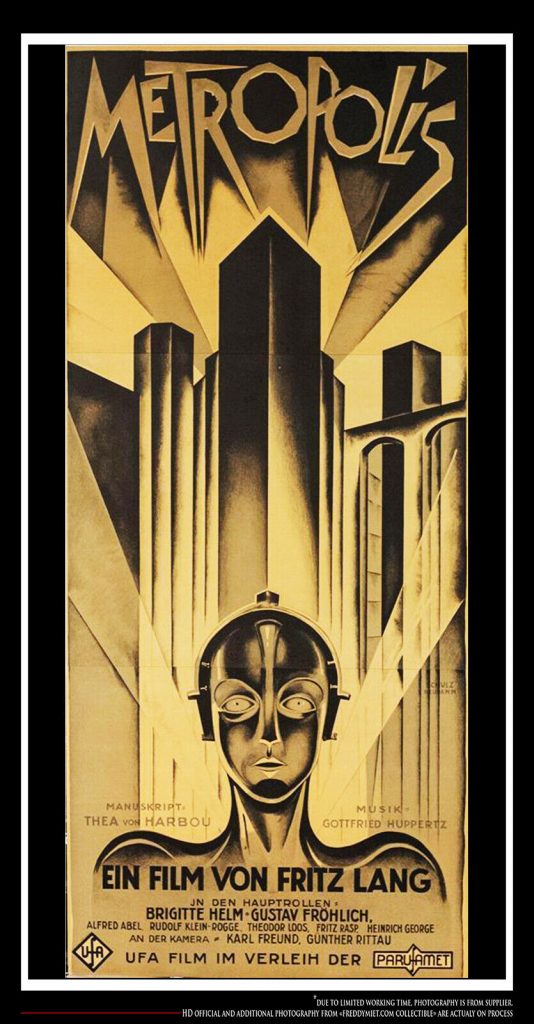

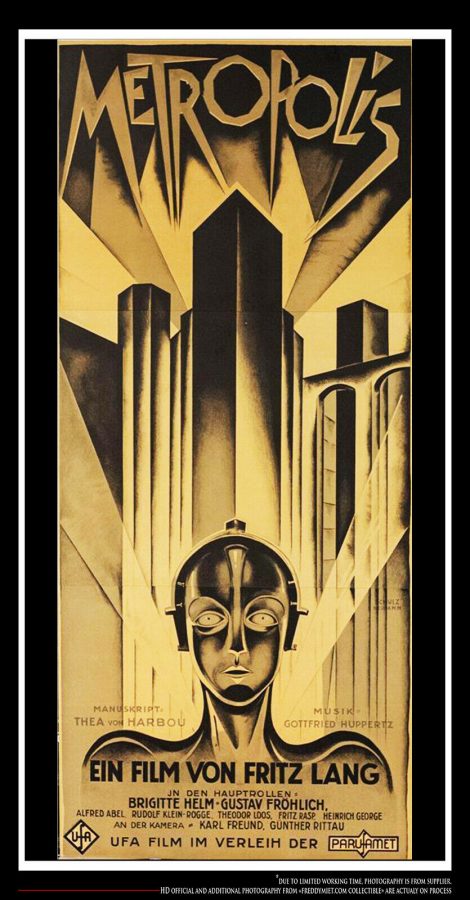

Original poster for METROPOLIS, 1927.

The reason that I am bringing up this method is because I note similarities between the acting in German expressionist films, such as Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari – the 1920 silent horror directed by Robert Wiene – and the techniques used by Lecoq. Most of the emotion and action in Metropolis is explained by dramatic movement and facial expressions, along with the occasional use of mouthing and captions, though these are limited. In a time where language seems to be the most prominent device used by contemporary film to guide and explain a storyline, it is refreshing and fascinating to watch a film that relies on the skill and versatility of its actor’s mime to develop and carry a storyline. Maria – the love interest of protagonist Freder and also the ‘saint’ of the underground workers, who prophesizes the arrival of a ‘mediator’ who will unite the ruling and working classes – has her face ‘taken’ and transposed onto the face of a robot by the dictator of the city (Joh Fredersen, Freder’s father) in order to quell the possibility of a rebellion by the workers. Maria is a mesmerizing character, because her actor – Brigitte Helm – takes on both the role of the innocent Saint Maria and the robot, or The Machine Man. Helm’s captivating use of body contortion and facial expressions makes her equally credible in both roles; the robot is highly sexualized, with heavy eye makeup and a malicious, crazed grin, while Maria is meek, near-bare-faced, and gentle.

Watching Helm work made me want to discover more about the Expressionist film movement, and to learn how I could learn to use my body and face as tools upon which to create stories and words without ever opening my mouth to speak. I have always relied on language throughout my acting career to date, though this might sound like an obvious claim to make. For most acting jobs, one is required to learn a script and is then told how best to move in order to create meaning from this script. I would generally consider myself to be a method actor; when learning to play a character, I find my thoughts and feelings begin to become one with the part I am to play, and even sometimes implementing aspects of these characters into my ‘real’ life. When learning the script for Measure for Measure (Shakespeare’s 1604 dark comedy), I quickly understood the advantage I had over some of the other actors in that I understood what Shakespeare was saying, whereas those from a less-literary background (I studied Literature for my Undergraduate degree) found more difficulty in interpreting the early modern vernacular of the play. But when I look back now, I think that what may have seemed to be an advantage – the ability to dissect and interpret Shakespeare’s work from a linguistic point of view – might have impeded my ability to freely embrace and embody my role as Isabella. I placed too much importance on what I was saying, and not enough on how I could say just as much by using movement and facial expressions. I was complimented on my performance, and I do believe that I did justice to Isabella’s character, but I find it interesting to think back on the methods I used to approach my role and to consider how I could have bettered my interpretation.

In the 1920s, countries were beginning to experiment with new techniques and styles of cinema, partly due to the poor economic states of many European countries after World War II. Many directors started to create dystopias and science fiction works to illustrate the changes that were occurring around them in technology, authority, fashion, art, and writing. Some of the earliest Expressionist (art which employs a distortion of reality to express the ideas and emotions of its creator) film creators were forced to be innovative in their approach to film-making due to the limited budgets they had to play with. This led to such techniques as painted shadows (see The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari) and paper set-designs (Metropolis) which create a sense of distortion and unease due to the oddity of the images they produce. In Metropolis, the images of the city are terrifyingly oppressive due to their harsh angles and oddly inaccurate shadows. The trend in these films was a rejection of realism and an emphasis on the possibilities of the future and whatever shapes, textures, and emotions the director might have believed the future would materialise in.

German Expressionism was cut short after the 1930s, but its impact was long-lasting and Nazi films made use of the tropes of Expressionism to create anti-Semitic propaganda. Later on, directors such as Alfred Hitchcock, Tim Burton, and Ridley Scott would use techniques in their films influenced by the Expressionist film movement. The acting in German Expressionist cinema was just as impactful in the cinematic world as the sets and styles of the films themselves. During the filming of Metropolis, Lang forced his actors into near-perilous circumstances in order to increase the veracity of their performances. When, near the end of the film, Maria (Brigitte Helm) as The Machine Man is burned at the stake, Lang insisted on using actual fire to burn the detritus beneath her tied-up body. This purportedly led to Helm’s dress catching fire. Prior to this moment, Maria is forcefully dragged by her hair by another actor (Grot, the man who works the ‘heart’ machine which keeps the city running), which she said was ‘[not] fun at all’ in a later interview. Lang wanted to create an environment whereby the actors would be forced to act more genuinely in their roles, and despite the controversy of such techniques, it certainly did lead to an astounding performance by all of the actors in the film. The suffering, anger, distress, and panic of the characters in the film is almost haunting in its sincerity, and almost all these emotions are conveyed to us without the use of any dialogue.

Human language has evolved so far as to develop the unprecedented ability to use words to form abstract thoughts about the future, to recall past events, and to create new ideas in the present. How wonderful it is that we have the capability to produce innovative works of fiction using our complex grasp of language and our knowledge of literary history. In theatre and film, however, I think that language can sometimes impedes an actor’s ability to freely embrace their art because they find themselves too focused on perfectly regurgitating lines as opposed to really feeling what those lines actually mean. Metropolis was, for me, a perfect study on how powerful physical acting can be, and how easily one can follow a narrative without the need for dialogue. This form of theatrical expression seems intrinsic to humans; children, while they might lack the linguistic ability to communicate freely with other humans, learn to navigate their world by reading the faces and bodies of people around them, and by taking in stories through picture books and objects around them. We need only look at a young child’s face to understand if they’re happy, hungry, uncomfortable, distressed, or tired. If we look to one of the most popular children’s television shows, Pingu, we see that it uses a fictional dialect to tell its stories, yet we have no problem understanding its narratives because we can use the visual cues it offers as well as the tonal implications of the language it employs.

Metropolis ends on a happy note, whereupon the ‘mediator’, Freder Fredersen, joins together the ‘head’ (the ruling class) with the ‘hands’ (the working class) using the ‘heart’. Trumpets blare an uplifting final hoorah as the workers walk up the steps to the cathedral in a pyramid formation and watch as the head and hands shake hands. A black screen covers this happy scene with the words ‘THE END’.

===========

The home page of this Carl Kruse blog is at https://carlkruse.net

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Hazel include Reflections on Montmartre, the Legacy of the Satyr, and the World of Wearable Art.

Also find Carl Kruse on the Princeton academia site.

Respect Fritz Lang’s beautiful efforts but I never though Metropolis was all that and don’t understand its endearing popularity.

I remember the song “101 point 111 101 point 111 101 point 111 on the dot” from the musical derived from Metropolis some time ago.

Beautifully shot but might it be overrated looking back in time?

I dunno, that almost a century after the film was made we are still talking about it might suggest METROPOLIS isn’t so overrated after all?

Carl Kruse

Precisely.