by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog A cyanotype is created very easily. Whether it is a composition of any worth is harder to say. A little later in the day of photographic discovery, when the desire to successively sustain an image in print captivated scientists, the cyanotype was discovered. Immediately recognizable for

Category: Photography

Visit to the Studio of Artist Hubertus Hamm in Munich

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog in conjunction with the Ivy Circle is happy to forward an invitation from the Wharton Club of Germany and Austria for a visit to the studio of renowned artist Hubertus Hamm in Munich to take place March 12, 2025. The invitation follows:. We are delighted to invite

Photography Over Time

By Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog 1. We are very aware these days of our submersion in the image; that much of our cultural meaning and awareness originates in the consumption of, production of, and of our being represented by images. The burning questions and controversies around the latest development in A.I.-related

Upcoming: Adele Schwab Photo Exhibit in Berlin

by Carl Kruse My friend Adele Schwab has organized a photo exhibit in Berlin on two dates: 19 November 2021 (Friday) from 21.00-22:30. 20 November 2021 (Saturday) from 17.00-18.30. Adele Schwab. Photograph from the artist’s website. Her exhibit is titled, “Seeing the Unseen” an audio visual project that attempts to make air “visible” and investigates

Steve McCurry: Vulnerability Made Immortal

By Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Member of the Magnum, Steve McCurry graduated in 1974 in Cinematography and Theater from the University of Pennsylvania. He began work as a freelance photographer in the late 1970s, dispatching reports from India and Afghanistan, the countries with which his work is most identified. The turning

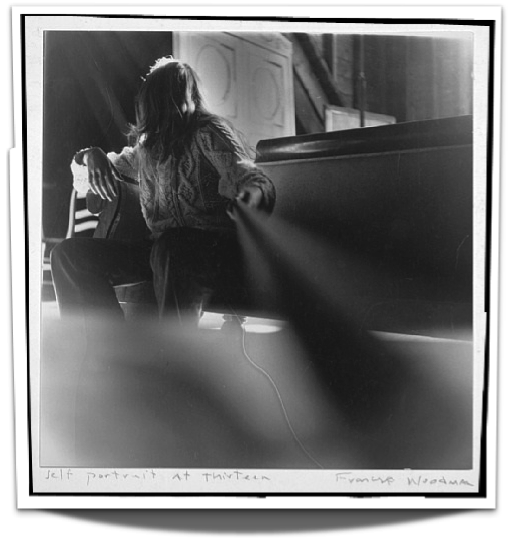

Between Introspection and Surrealism: the Photography of Francesca Woodman

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog One day in 1977, a young girl entered the “Maldoror” art gallery in Rome, handed the owner a gray box and exclaimed: “I’m a photographer!” She is not yet twenty and her name is Francesca Woodman. Born in Denver in April 1958, Francesca was the daughter

At Play With National Geographic’s YOUR SHOT

YOUR SHOT On National Geographic by Carl Kruse UPDATE: 7 November 2019: As of 31 October 2019, National Geographic has sadly closed the YOUR SHOT section of its site. This post remains for historical reasons. There are fortunately many other sites online to share images. We recommend FSTOPPERS and 500px. Both sites have high quality

Vicky Surveys Photography for Carl Kruse

As Carl Kruse is away, we let intern Vicky Srivastava write an article on the different types of photography for this blog update. His first on the internet. Photography and Its Unending Types Photography is an art of different forms and types. Most people would have it that the fundamental purpose of photography includes preservation

Jack Delano- Experiments in Light Photography

Some time in the early 1990s I came across Jack Delano’s work in a photography book titled “Puerto Rico Mio: Four Decades of Change.” Here Mr. Delano compared images from his first visit to the island in the 1940s with those he later made of the same sites 40 years later. Delano had first traveled