by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog I was speaking with a friend of mine a few days ago about innovations in art, or the lack thereof. He was of the opinion that nothing new was being made, that we, as a collective, were stagnating in our incessant recycling of the old,

Category: Arts

Yury Kharchenko Art Exhibit at the Hällisch-Fränkisches Museum

by Carl Kruse After the terrorist attack by Hamas on October 7th in Israel and the Gaza war, life changed for artist Yury Kharchenko. And now,, the Hällisch-Fränkisches Museum is showing works by the artist in a solo exhibition from June 29th to October 20th, 2024. The Berlin-based artist was born in Moscow in 1986.

Another Art Exhibit With Michael Dyne Mieth

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog invites all to another exhibition and social gathering in Berlin as part of its Art series with German artist Michael Dyne Mieth. Join us Thursday, May 23, 2024 from 6:30pm – 9:30pm at Dorotheenstr 83, 10117 Berlin. Dyne will exhibit a collection of his works spanning his

Ememem – Puddles of Color

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog It is dawn, and the city is not awake, because in France, cities sleep when the night rolls through them. Maybe a light shines out from the backroom of a bakery, where a few bakers with sleep in their eyes pound and shape dough beside

Photography Over Time

By Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog 1. We are very aware these days of our submersion in the image; that much of our cultural meaning and awareness originates in the consumption of, production of, and of our being represented by images. The burning questions and controversies around the latest development in A.I.-related

Underground Art Series in Berlin: Michael Dyne

by Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog invites all to another exhibition and social gathering as part of its Underground Art series this time with German artist Michael Dyne Mieth. Join us Saturday, November 25 starting at 6:30pm underneath the restaurant Papá Pane di Sorrento at Ackerstrasse 23, 10115 Berlin. Dyne will exhibit a

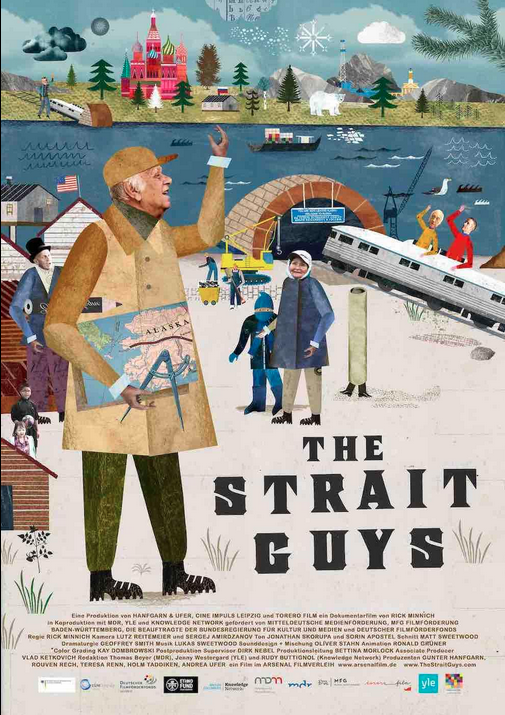

The Strait Guys Film at the Global Peace Film Festival

by Carl Kruse Filmmaker and friend of the Carl Kruse Arts Blog, Rick Minnich, cordially invites you to the closing night screening of the documentary film ‘The Strait Guys’ taking place at the Global Peace Film Festival on Saturday, September 23, 2023, 7:30-9:15 PM, at Crummer Auditorium, Rollins College, Fairbanks Ave. & Interlachen Ave., Winter

Open Studios in Berlin – October 1, 2023

by Carl Kruse Summer is finished and with most folks back in Berlin the Carl Kruse Arts Blog would like to invite all to an “open studios” afternoon of several visual artists, first and foremost that of our friend Helena Kauppila, who was featured in our last blog post here. The event takes place Sunday,

Upcoming Helena Kauppila Solo Exhibit in Berlin

By Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog invites all to the vernissage of artist (and blog friend) Helena Kauppila’s solo exhibition titled SYSTEMS SYMPHONY with an opening reception Wednesday, August 30th, 2023 starting at 7 pm in Berlin. For the reception, Kauppila has prepared some remarks reflecting on the blending roles of color, movement,

Giorgio Morandi and Reflections on Still Life Painting

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The Estorick Gallery in London is now dedicating four of its rooms to Giorgio Morandi. These are not the grand spaces you find in places like the National Gallery or the Louvre; the gallery is a converted Georgian town house and it is impossible to