by Carl Kruse On January 8, 2022 the Deutschlandfunk Kultur hyperlink – radio program invited our artist friend Yury Kharchenko to discuss the cost of art, both from a material and figurative perspective. The program was hosted by Michael Köhler and translated from German to English by Carl Kruse, who is responsible for any errors

Author: Carl Kruse

Performance Art – SIX VIEWPOINTS

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog I arrive in the room. Other students are milling around, some stretching in the blinding winter light stretching in from the tall windows on the far side of the room, others laughing in little clusters, some silently penning down notes in blank-paged cahiers. We are

Upcoming Kharchenko Retrospective at The Kunstverein Krefeld

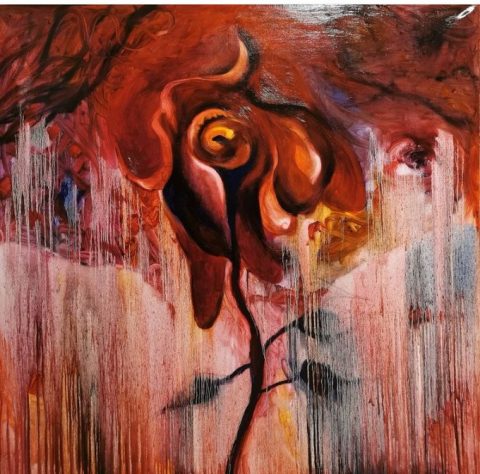

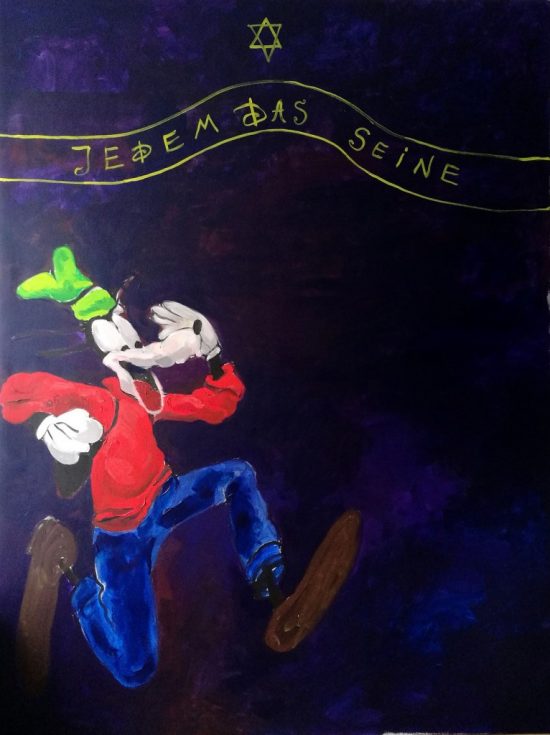

by Carl Kruse From March 25 through May 1, 2022, the Kunstverein Krefeld in Germany will hold a retrospective of the works of Russian-German artist (and friend of our blog) Yury Kharchenko. This solo exhibit will focus on two phases of Kharchenko’s work: the first on his so-called Auschwitz paintings, which see superhero figures, such

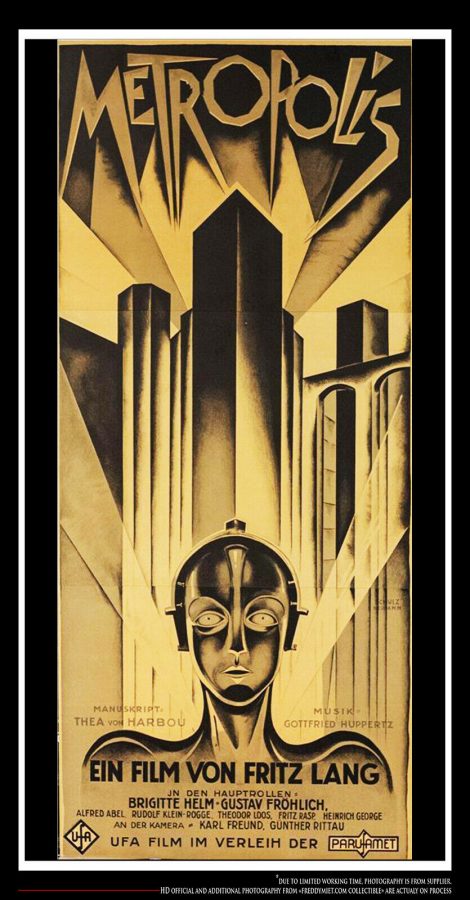

Metropolis

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The stage is set. Three pyramids built up of myriad buildings and angles forge forth unto the screen. Spotlights dance in symmetrical lines, lighting up sections of the structures like a stage. The buildings blur into three black pieces of machinery plunging up and down,

Short Reflection on Kraftwerk

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Four men, a measured distance apart, standing disinterestedly over four synthetic sound systems. There is a small crowd seated in front of them. The sound that permeates the room comes from the barely moving men, and it is one of melodic and harmonic simplicity. It is

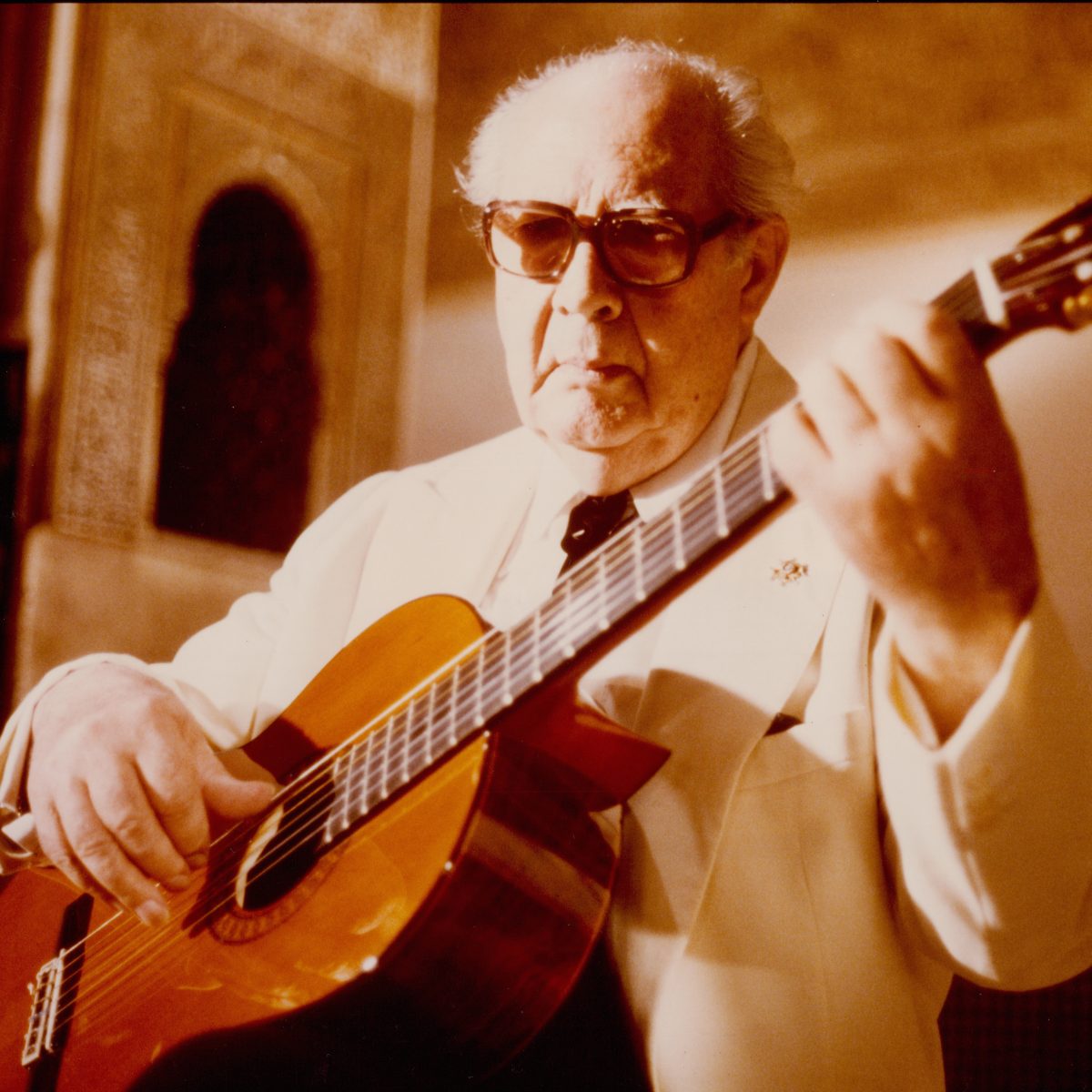

Segovia and the Guitar

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The seventy-four-year-old maestro sits plump in a large wicker chair. His gut ovals as he looks out from his balcony towards the Mediterranean Sea. His home is large upon the hill, overlooking an olive grove which blinks out the Andalusian heat. Close by is Granada, the

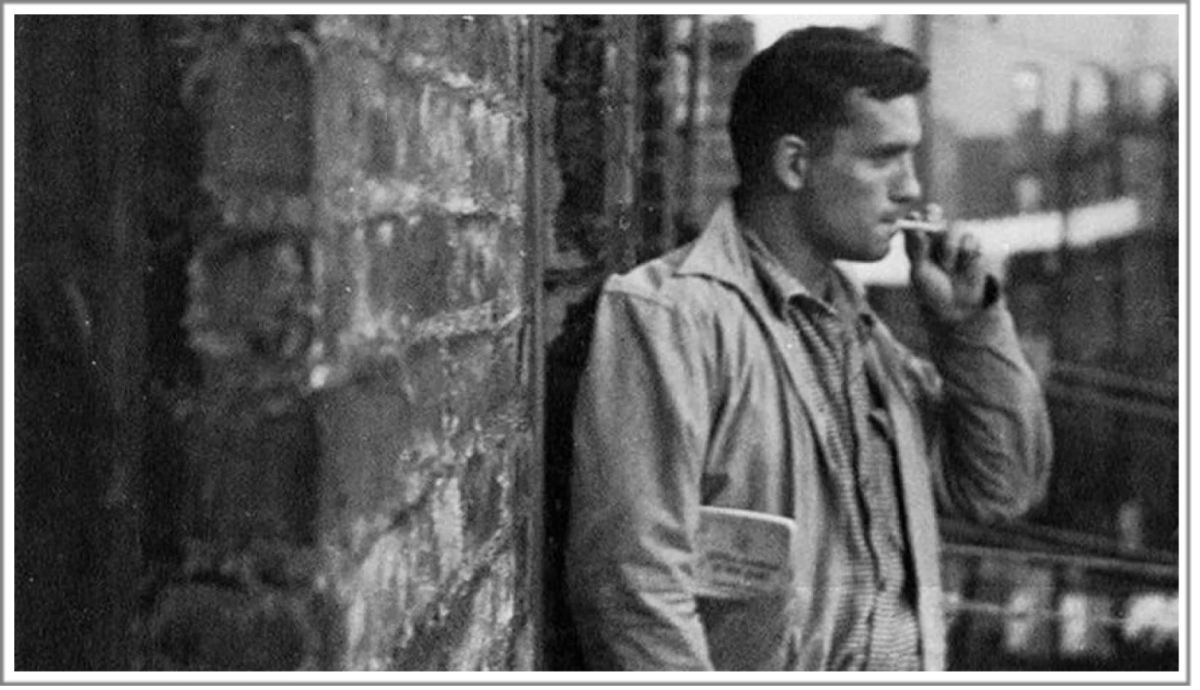

The Beats – Driving Cross Country in Search of Eternity

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, [… ] with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls, [… ] who drove

Upcoming: Adele Schwab Photo Exhibit in Berlin

by Carl Kruse My friend Adele Schwab has organized a photo exhibit in Berlin on two dates: 19 November 2021 (Friday) from 21.00-22:30. 20 November 2021 (Saturday) from 17.00-18.30. Adele Schwab. Photograph from the artist’s website. Her exhibit is titled, “Seeing the Unseen” an audio visual project that attempts to make air “visible” and investigates

Bowie’s Alter Ego That Transcends Death: Major Tom

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog It is 1969, and the young David Jones, better known as David Bowie, begins to ascend the world stage thanks to the launch of his latest single, Space Oddity. Likely influenced by the space race, the tales of Ray Bradbury, and undoubtedly by 2001: A Space Odyssey. The single

Upcoming: An Artist Talk With Yury Kharchenko

by Carl Kruse Our artist friend Yury Kharchenko joins a debate titled “Art, Culture and Memory” at the Wallraf Museum in Cologne, Germany, on 5 October 2021 from 19.00-21.00. The chat will deal with issues surrounding Holocaust remembrance, the culture of remembrance and the cult of guilt. Yury Kharchenko. Photo: New York Times. In his