by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Art’s Blog Before her face was associated with one of the most evocative works of art of all time, even before becoming the symbol of an incredible legal affair, Adele Bloch-Bauer was simply a beautiful woman. Born in 1881 in Vienna, Adele had grown up in the cultured

Category: Arts

The Monastery Festival 2022

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Close to the border of Netherlands, the small German town of Goch lies, hugged by the Rhine that cuts through North Rhine-Westphalia. Since 2018, the grounds of Graefenthal Abbey in Goch have hosted the Monastery festival, made possible by the support of The Gardens of Babylon

In Memoriam: Vangelis

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog The Greek composer and musician Evangelos Papathanassiou passed away in Paris recently. Better known as Vangelis, the award-winning musician and beloved film-score composer. Obituaries and the programs of his life abounded against the fact. A career of over fifty years, and not one that could be characterized

The San Berillo District in Sicily

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog Hidden from the great palaces of Corso Sicilia, Italy, in the heart of the historic center of Catania stands the San Berillo district, a neighborhood that has been wounded, emptied, rebuilt, never completed. We discovered it by chance, my boyfriend and I, wandering around the city of

“Comic Kids:” Teaching At-Risk Youth About Art

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog It is positively clear that art sustains and nourishes something deep in our minds. It is such an obvious statement that it may appear as a platitude, or, perhaps even worse, appear as a given fact that one need not bother about; art will be there housed

What Does Art Cost -With Yury Kharchenko

by Carl Kruse On January 8, 2022 the Deutschlandfunk Kultur hyperlink – radio program invited our artist friend Yury Kharchenko to discuss the cost of art, both from a material and figurative perspective. The program was hosted by Michael Köhler and translated from German to English by Carl Kruse, who is responsible for any errors

Performance Art – SIX VIEWPOINTS

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog I arrive in the room. Other students are milling around, some stretching in the blinding winter light stretching in from the tall windows on the far side of the room, others laughing in little clusters, some silently penning down notes in blank-paged cahiers. We are

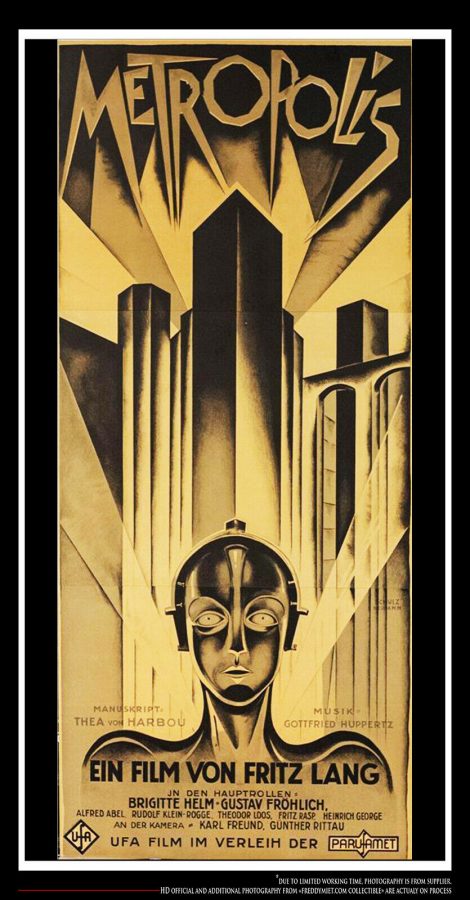

Metropolis

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The stage is set. Three pyramids built up of myriad buildings and angles forge forth unto the screen. Spotlights dance in symmetrical lines, lighting up sections of the structures like a stage. The buildings blur into three black pieces of machinery plunging up and down,

Upcoming: Adele Schwab Photo Exhibit in Berlin

by Carl Kruse My friend Adele Schwab has organized a photo exhibit in Berlin on two dates: 19 November 2021 (Friday) from 21.00-22:30. 20 November 2021 (Saturday) from 17.00-18.30. Adele Schwab. Photograph from the artist’s website. Her exhibit is titled, “Seeing the Unseen” an audio visual project that attempts to make air “visible” and investigates

Upcoming: An Artist Talk With Yury Kharchenko

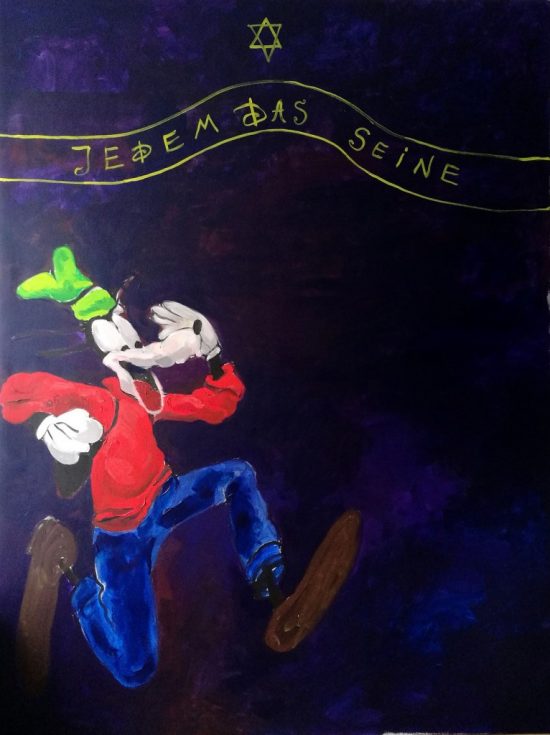

by Carl Kruse Our artist friend Yury Kharchenko joins a debate titled “Art, Culture and Memory” at the Wallraf Museum in Cologne, Germany, on 5 October 2021 from 19.00-21.00. The chat will deal with issues surrounding Holocaust remembrance, the culture of remembrance and the cult of guilt. Yury Kharchenko. Photo: New York Times. In his