by Carl kruse Ahoy art friends, especially those in South Florida. A college friend has loaned 16 ancient artifacts from his private collection to pair with 16 works of modern artists in an exhibit called “Justified + Ancient.” In this exhibit, contemporary artists display their work side by side with ancient pieces, dating from 3000

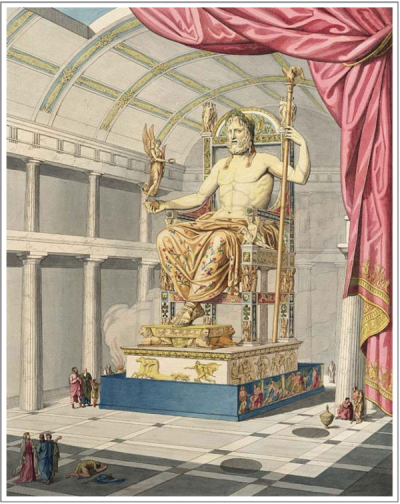

Zeus in Olympia: What Happened to the Fourth Wonder of the World?

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog In the northwest of the Peloponnese there is a small village of about 150 inhabitants called Elis, which retains vestiges (even in its modern buildings) of its ancient significance. The city was once the most important in the region, controlling Olympia, where the Olympic Games were

Acting and Art: Channeling Animals

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The studio floor is covered in bodies. They are curled and strewn and spread and sprawled, as though they were dead. But they are not. Some breathe shallowly, quickly, as if their hearts fluttered about like moths. Some breathe deeply, forcing air bull-like through their

The 3-D Street Art of Insane 51

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Stathis Tsavalias, known as Insane 51, has recently been characterizing the streets of Bristol (England) with a delicate practice of double-exposure. His formal education in the Athens School of Fine Art has led him towards the street canvas where he has successfully experimented with the large-scale

Using Radio Telescopes to Create Art

by Carl Kruse Artists work in many mediums – paint, wood, marble, words, music, dance, film. But there are some that journey beyond the traditional into radio signals, actual consciousness, neuroscience, dreams and outer space. Meet Daniela de Paulis, an artist whose trajectory began with dance and traditional media who now focuses on the exploration

The Woman in Gold: the Story of Klimt’s Muse.

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Art’s Blog Before her face was associated with one of the most evocative works of art of all time, even before becoming the symbol of an incredible legal affair, Adele Bloch-Bauer was simply a beautiful woman. Born in 1881 in Vienna, Adele had grown up in the cultured

The Monastery Festival 2022

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Close to the border of Netherlands, the small German town of Goch lies, hugged by the Rhine that cuts through North Rhine-Westphalia. Since 2018, the grounds of Graefenthal Abbey in Goch have hosted the Monastery festival, made possible by the support of The Gardens of Babylon

In Memoriam: Vangelis

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog The Greek composer and musician Evangelos Papathanassiou passed away in Paris recently. Better known as Vangelis, the award-winning musician and beloved film-score composer. Obituaries and the programs of his life abounded against the fact. A career of over fifty years, and not one that could be characterized

The San Berillo District in Sicily

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog Hidden from the great palaces of Corso Sicilia, Italy, in the heart of the historic center of Catania stands the San Berillo district, a neighborhood that has been wounded, emptied, rebuilt, never completed. We discovered it by chance, my boyfriend and I, wandering around the city of

“Comic Kids:” Teaching At-Risk Youth About Art

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog It is positively clear that art sustains and nourishes something deep in our minds. It is such an obvious statement that it may appear as a platitude, or, perhaps even worse, appear as a given fact that one need not bother about; art will be there housed