by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog This is a photograph of two women in front of a photograph of couples dancing. You do not know these women. What can we deduce from this image? Many a thing. The old woman is looking at the camera. She knows she is being watched.

Category: Arts

Upcoming Charlottenburg Gallery Walk

By Carl Kruse The Carl Kruse Arts Blog invites all to the gallery walk scheduled for June 2-3, 2023 in the Charlottenburg neighborhood in Berlin, Germany. Known as the “Charlotten Walk,” the two days will see more than 40 galleries – from the established to the up-and-coming – open their doors to all. Hours for

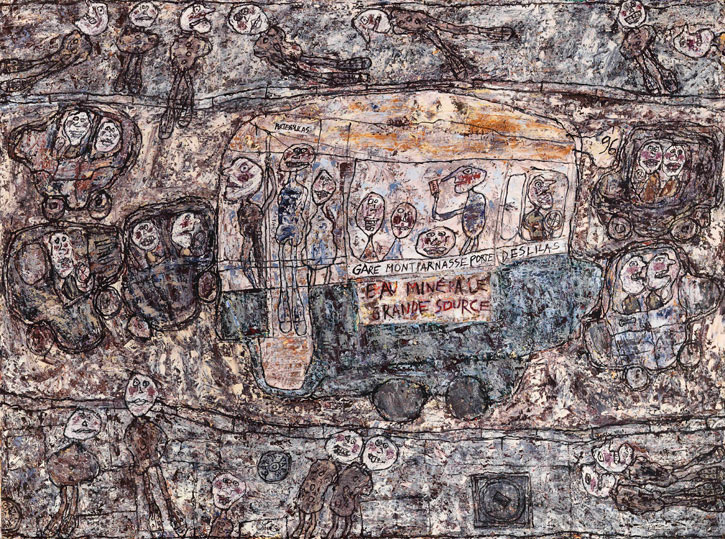

Art Brut, or Outsider Art.

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Sometime in the 1940s, the artist Jean Dubuffet coined the term “Art Brut” which roughly translates as “Raw art”; un-cooked and close to the initial mood of creation; or, the closest representation of the individual’s creative urge before the influence of learning. Much of Modernist art

Comic Kids on the Kelly Clarkson Show

by Carl Kruse It was back in 2018 that Reed and Kat Horth had an idea born from their desire to give back to kids in Miami’s under-served communities in the best way they knew how…with art. They started teaching a weekly comic and cartoon illustration class for children at Big Brothers Big Sisters Miami.

When the Show is Over

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The mist has lifted, and life is back. It is an abyss, a swamp of unknowing and learning how to live without the glistening sheen of adrenaline that glosses over your eyes for the weeks and days preceding and encompassing a show. You lie flat,

Finding My Clown: A Distilling of the Human Condition

by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog The fundamental reality of creation is solitude. This is what Lecoq tells us, and, when I turned around and faced the audience, clothed with my red nose for the first time, I did indeed feel very alone. We had started doing clown the week before,

Justified + Ancient Exhibit

by Carl kruse Ahoy art friends, especially those in South Florida. A college friend has loaned 16 ancient artifacts from his private collection to pair with 16 works of modern artists in an exhibit called “Justified + Ancient.” In this exhibit, contemporary artists display their work side by side with ancient pieces, dating from 3000

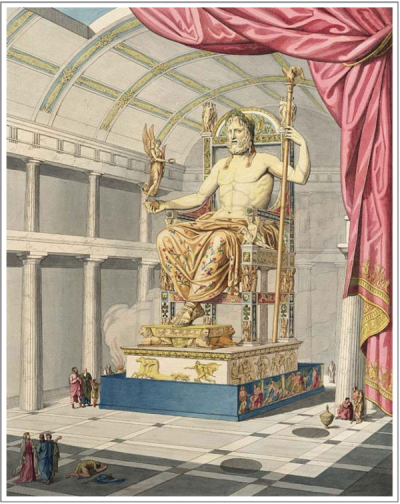

Zeus in Olympia: What Happened to the Fourth Wonder of the World?

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog In the northwest of the Peloponnese there is a small village of about 150 inhabitants called Elis, which retains vestiges (even in its modern buildings) of its ancient significance. The city was once the most important in the region, controlling Olympia, where the Olympic Games were

The 3-D Street Art of Insane 51

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Arts Blog Stathis Tsavalias, known as Insane 51, has recently been characterizing the streets of Bristol (England) with a delicate practice of double-exposure. His formal education in the Athens School of Fine Art has led him towards the street canvas where he has successfully experimented with the large-scale

Using Radio Telescopes to Create Art

by Carl Kruse Artists work in many mediums – paint, wood, marble, words, music, dance, film. But there are some that journey beyond the traditional into radio signals, actual consciousness, neuroscience, dreams and outer space. Meet Daniela de Paulis, an artist whose trajectory began with dance and traditional media who now focuses on the exploration